Key points

The 10 Year Health Plan (10YHP) introduced integrated health organisations (IHOs) as a population-based contracting approach to improve outcomes for patients and improve value for money through greater allocative efficiency.

IHOs are a way to align financial flows and incentives to enable the NHS to shift more spending toward earlier and more cost-effective interventions, helping to fix the NHS.

NHS leaders describe IHOs as containing three main elements: 1) a capitated contract commissioned by an ICB which transfers responsibility for the health outcomes of a whole population within a defined geography to a ‘host’ provider, 2) with sub-contractual arrangements between a host provider and partner providers that cover the delivery of care services beyond those delivered directly by the host, 3) enabled by a locally agreed mechanism that ensures collaboration and shared decision-making across all providers.

Based on engagement with over 30 healthcare leaders from primary care, community, mental health and acute providers and ICBs, this report presents considerations for local leaders and the government to develop IHOs across four components:

1. Contract – A capitated contract for a whole population awarded by an ICB to a host provider, which holds the IHO contract on behalf of a group of providers, then delivers and/or sub-contracts services, aligning financial incentives between providers to reduce downstream demand.

2. Structure – A high-performing foundation trust as the ‘host provider’ will need collaborative structures to work with other care providers in partnership including local government.

3. Governance – While an IHO will not be a new legal entity, the host provider’s governance should adapt to focus on improving population health and the sub-contracting of services from other providers, not just service delivery and organisation performance.

4. Behaviours and leadership – Beyond hard mechanisms, the success of IHOs will depend on trust, relationships and shared purpose across partners. Leadership should be about convening, not controlling.

Host providers, collaborative arrangements and expected outcomes should be agreed locally, rather than imposed from above. While the first wave of IHOs might be authorised centrally, they should in future be initiated by ICBs.

However, misaligned national policy risks thwarting IHOs. The National Oversight Framework’s financial and performance metrics are too focused on individual organisations, disincentivising collaboration between organisations needed to deliver an IHO contract.

Barriers in competition should be addressed, in consultation with the Competition and Markets Authority, and legal changes made to better enable social care and public health services to be included in IHO contracts in future.

While IHOs are intended to improve allocative efficiency and financial performance, limiting IHO contracts to only ‘high-performing’ foundation trusts risks exacerbating performance variation and inequalities. A clear pathway is needed for organisations with lower performance in some areas, but strong leadership capability and partnerships, to hold an IHO contract.

This report presents considerations for local leaders and the government to develop IHOs across four components of contract; structure; governance; and behaviour and leadership.

Download a one-page summary of the report's key considerations and recommendations.

Introduction: Where have IHOs come from?

The challenges facing the NHS, although not unique to England, are considerable. Demand for healthcare services continues to rise disproportionately compared to the rest of the economy, exacerbated by an ageing population, increasing co-morbidities and continuously evolving technology. Long-term conditions are also becoming the norm, with nearly half the population suffering from one, and this continues to eat away at a sizeable amount of healthcare expenditure. Common mental health conditions in younger demographics are also becoming more prevalent. Demand for services is rising faster than the healthcare system’s capacity to meet it. These trends are straining public finances, reducing economic productivity and widening health inequalities.

In turn, waiting lists are growing and staff morale is reducing, as evidenced by ever-increasing instances of industrial action and declining satisfaction in the latest NHS staff surveys. All the while, public expectations of the NHS increase, driven by medical advances.

Ever-increasing healthcare spending is not a sustainable option. Instead, healthcare needs to be redesigned to increase overall system effectiveness. Shifting resources upstream towards earlier preventative and community care, managing demand and boosting allocative efficiency, can recover services, reduce waiting times and put the NHS on a sustainable footing.

The 10 Year Health Plan (10YHP) seeks to do this by shifting care from hospital to community. To help achieve this, the plan intends to devolve to and empower local leaders with significant freedoms for the highest performers via a reinvented, 'advanced' NHS foundation trust (FT) model and establishment of integrated health organisation (IHO) contracts. Advanced FTs will operate on the same core philosophy as their predecessors, with enhanced autonomy, control of board composition, financial freedom and the ability to raise capital. The 10YHP states that the most advanced FTs – with a track record of meeting core standards, improving population health, forming partnerships and maintaining financial sustainability – can receive capitated contracts to become IHO host providers.

The concept of IHOs draws on the international case studies of accountable care organisations (ACOs) and domestic experience. In countries such as the USA and Spain, ACOs are generally a single provider in charge of the health budget for a geographically defined population, tasked with delivering longer-term outcomes within a fixed budget. In England, the 2014 Five Year Forward View (FYFV) outlined multispecialty community providers (MCPs) and primary and acute care systems (PACS), although the long-term, positive sustainable impact of these models was limited. Though they offered different approaches, they shared ‘a focus on places and populations rather than organisations’, emphasising a collaborative approach to care.

In the Health and Care Act 2022, integrated care boards drew inspiration from American ACOs, although differed as their primary responsibility was as commissioners, not providers. Despite not formally materialising, a diverse selection of integrated provider models has populated the provider landscape since 2012, and most providers are now working within a provider collaborative of some form, with all acute and mental health providers required to be part of at least one. In their joint report with NHS Providers, Browne Jacobson highlighted the utility of collaborative models in delivering safe, effective and sustainable services to their populations, as well as a beneficial response to challenges and risks. We are seeing a similar collaborative model developing in primary care.

This report, based on engagement across primary care, community, mental health, acute and ICB leaders from August to October 2025, explores the current state of play on integrated delivery models and next steps to move towards IHOs. The proposals set out in this report are based on the views of members of the NHS Confederation. This report is not a statement of national policy, rather it is a set of proposals intended to inform government policy and local practice. We would like to thank all the individuals we spoke to as part of this research, including our members and NHS England colleagues.

For a more detailed overview of the report’s aims and context, including examples of previous approaches to integrated care, please see the appendix.

1. What is an IHO?

1.1 Elements of an integrated health organisation

There is consensus among healthcare leaders on what an IHO is and broadly what it should intend to achieve. In their view, an IHO is not a new organisational form but a new integrated delivery model with three main elements:

1) a capitated contract commissioned by an ICB which transfers responsibility for the health outcomes of a whole population within a defined geography to a ‘host’ provider

2) sub-contractual arrangements between a host provider and partner providers which cover the delivery of care services beyond those delivered directly by the host

3) a locally agreed mechanism that ensures collaboration and shared decision-making across all providers.

The language used nationally and locally to refer to these different elements is important in facilitating a more supportive and collaborative approach. For instance, rather than ‘lead provider’, which implies an organisational hierarchy and could indicate a potential takeover, healthcare leaders would prefer subsequent national policy to refer to ‘host providers.’ That terminology is adopted throughout this report.

1.2 Purposes of an integrated health organisation

NHS leaders agree that the primary purpose of IHOs should be to improve population health outcomes and deliver better value for money by increasing allocative efficiency. By reducing competing financial incentives across services and sectors and overcoming fragmentation in how care is commissioned and delivered, IHOs are a way of enabling the NHS to shift more spending toward earlier and more cost-effective interventions and build services that better meet the needs of communities.

The specific outcomes IHOs are expected to deliver should be defined and incentivised locally by ICBs and providers. However, a small number of ‘big ticket’ outcomes that are set nationally may be beneficial. Outcomes may include lower cost per head of population, reduced health disparities, improved and more equitable healthy life expectancy and reduced avoidable mortality. Congruence between IHO outcomes and outcomes that feature in other contractual models is also essential, including the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) in primary care and the neighbourhood provider contracts outlined in the 10YHP.

Healthcare leaders emphasised the importance of agreeing the purpose of an IHO up front to avoid misalignment after an IHO contract is awarded. There were concerns that tight financial envelopes may mean some organisations view IHOs as a route to secure more funding or autonomy, rather than as a mechanism for driving partnership working and directing resource to the correct place for the right outcomes. To succeed, the relationship between the ICB, the IHO host provider and partner providers must be collegiate, not adversarial. This will demand clear oversight arrangements and governance, aligned incentives and strong convening leadership from the ICB.

Becoming a host provider, in the words of one community trust leader, should not be seen as a ‘badge of honour’, but should be seen in the following terms:

“I've just taken on responsibility to support the aims of a partnership that I'm a full member of and an equal member of, but I'll happily do some of this technical stuff on behalf of the partnership.”

1.3 Scope of an IHO

The 10YHP states that IHO host providers will have the opportunity to ‘hold the whole health budget for a defined local population’. One of the founding features of capitated contracts is that they cover people from cradle to grave, providing an incentive to prevent ill health along a life course.

Healthcare leaders feel strongly the scope of an IHO contract should be defined locally by ICBs and providers, based on the IHO’s agreed purpose, local geography, patient flows, existing provider configuration and population need. A local approach will be taken to defining neighbourhood contract boundaries. Alignment across these footprints will be crucial so that ICBs can set consistent outcomes (this link is explored further in section 2.1).

Local leaders suggested a range of potential population sizes. Typically, we expect an IHO contract will serve a place or unitary authority footprint (250,000-500,000 people) but could also extend to a borough or provider collaborative scale (1-1.5 million people). These footprints are generally smaller than ICSs while remaining large enough to cover a meaningful range of services and populations. Some suggested starting small and building up.

1.4 IHOs are not the only model

For many areas, IHOs may not be a viable or desirable option in the short term. Therefore, while this report focuses on how to hold IHO contracts, there are multiple other ways that local systems can, and have been, integrating care and improving population health at a lower cost.

For instance, providers are already exploring various forms of increased provider collaboration via statutory committees, joint ventures, host provider models and group models. 1 These can each support service integration in areas with and without an IHO. Provider collaboratives act as a supporting structure for delivering care across different settings, including neighbourhoods, by standardising care, managing workforce and delivering services at scale. This is explored further in section 2.2. The 10YHP also introduces a range of other contractual mechanisms to transform care, including Year of Care Payments and two new neighbourhood provider contracts. IHOs can co-exist with other lead provider arrangements for specific services and pathways.

Some healthcare leaders issued the need for caution in the rollout of IHOs, suggesting the ‘first wave’ of IHO host providers be treated as pilots to avoid ‘putting too many eggs in the IHO basket’. This reflects lessons from previous attempts to implement similar approaches, recognition of the wider operating environment and the complexities involved and concerns about the alignment of other policy levers (explored further in chapter 3).

Successfully delivering an IHO requires a high level of system readiness, including strong provider capability and performance, system maturity, trusted relationships and strategic commissioning expertise. These conditions will not be present in all areas yet, reinforcing our view that IHOs are not the only, or the best, option for every system.

Chapter footnotes

- 1. See Paul Roberts, ‘Greater Than the Sum of its Parts?: Sharing Board Leadership Between NHS Trusts (NHS Confederation, 2024) for an analysis of the learnings from shared leadership models in provider trusts in England. ↑

2. The four components to holding IHO contracts

Healthcare leaders outlined four components to holding an IHO contract:

- agreeing the contractual form

- finding the right structure

- reimagining governance

- fostering the right behaviours and leadership by aligning the soft levers.

These issues would need to be considered by NHS leaders when determining whether an IHO is the most suitable model. In our annex, we have also included a list of questions to prompt and guide discussions between system partners about whether an IHO is the right model for them.

2.1 Agreeing the contractual form

A contract for a geographically defined population

The distinguishing feature of an IHO is its capitated contract, which provides a single budget to cover healthcare services for a whole population. Unlike other available contracts, IHO contracts cover the provision of all healthcare services for that population, excluding the public health functions that local government is responsible for, 2 and services better commissioned at scale (either at an ICB, regional or national level), such as highly specialised care services. Other contractual forms are available for specific patient cohorts or service areas, such as Year of Care payments which were proposed in the 10YHP. 3

The ICB is responsible for awarding the contract, overseeing its delivery and analysing population health data to help inform sub-contracting decisions by the IHO host provider. Where no IHO host provider exists, the ICB will continue to commission services directly from providers.

The IHO host provider then provides some services directly and provides necessary sub-contractual arrangements for other services to appropriate providers. For example, a hosting community trust might sub-contract upstream to primary care or an acute trust might sub-contract downstream services. The contractual form will vary, drawing on the options defined in the NHS Payment Scheme. These include blended payments (including payment by activity), single- and multi-neighbourhood provider contracts (see more on this below), Year of Care payments and capitated sub-contracts that delegate responsibility for a subset of the population.

The host provider could sub-contract population health responsibility or service delivery to one organisation. Given that many providers operate across multiple geographies, it is possible that a single organisation may hold an IHO contract for one geographical population, act as a sub-contractor in another, and be part of a non-IHO system in a third. Assurance will need to be provided that the IHO contract is robust, provides financial value, and contains a clear allocation of risk and reward. 4

Strategic commissioning

IHO host providers will need strong strategic commissioning skills to effectively sub-contract services for their populations. Strategic commissioning differs from traditional commissioning in that it seeks to achieve a more proactive, data-driven and collaborative health service. This shift will require a transfer of expertise from the ICB to the IHO host provider, along with a redrawing of the traditional commissioner/provider boundary.

As the NHS Confederation set out in our vision of ICB strategic commissioning, strategic commissioning requires five core capabilities:

- Data analysis skills and digital capability to understand population health and plan proactive care

- Diplomatic skills to convene providers and facilitate collaboration

- System leadership skills to build cohesive teams across organisational boundaries

- Contract management expertise to manage contract performance and transform models of care

- Estate management capabilities to maximise the value from the available estate of all system partners.

Host providers will need capacity and capabilities in all these areas, alongside robust evaluation skills to understand the efficacy of sub-contracted services. They will also rely on ICBs’ analysis of population health need; regional commissioning of highly specialised services; and to co-ordinate with local government commissioned social care and other services, such as public health and housing. These relationships will be crucial to enabling IHOs to deliver the transformational shifts envisioned in the 10YHP.

Examples of similar models

The host provider and sub-contracting model aims to reduce competing incentives by aligning financial flows and outcomes across providers. It should provide a gain/loss share mechanism, ensuring all providers along a care pathway have a shared financial incentive to deliver care earlier and avoid downstream admissions. That is, if an upstream provider successfully prevents hospital admissions, all providers along the pathway benefit financially. See figure 1.

International health systems have successfully used host providers with capitated contracts to shift care to community settings and deliver better value. In the US, Medicare awarded a capitated contract to ChenMed, a primary care provider, to deliver and sub-contract services for people over 65 in Miami. 5 ChenMed assumed financial risk, covering any deficits but retaining any surplus from avoided secondary admissions. In this arrangement, ChenMed was essentially the IHO host provider, with Medicare functioning as the strategic commissioner. The financial flow incentivised the shift of resources from sickness to prevention and from hospital to community care, nearly halving average hospital inpatient days for over-65s compared to both the rest of Miami and to average admissions in England.

Figure. 1 Left: a typical ‘hub and spoke’ commissioning relationship between an ICB and providers. Right: a ‘chain link’ relationship between an ICB and providers, with an IHO establishing a link to align the financial flow and straddling the ‘purchaser-provider’ split. Collaboration between the providers is re-enforced by a structural relationship, as set out section 2.2.

Barriers

Procurement of services and contract management places an additional administrative burden on the host provider. As NHS England has required all NHS trusts and foundation trusts to reduce the growth in their corporate spend since 2018/19 by 50 per cent, there is a risk that foundation trusts may lack sufficient administrative capacity to take on the commissioning functions that come with being a host provider. 6

Competition concerns may arise for IHO host providers particularly where they will be responsible for commissioning services that both they, as a provider, and other providers in their area may be able to deliver.

Competition concerns and potential breaches could arise in several ways. Firstly, in terms of the procurement process undertaken by the host provider for subcontracting arrangements, which currently must comply with the requirements of the Health Care Services (Provider Selection Regime) Regulations 2023. Secondly, where the host provider can be said to have a dominant position in the market which allows it to unfairly restrict competition whether in its own market or in the downstream market, which may amount to a breach of Chapter 2 of the Competition Act 1998 (CA98). Thirdly, where providers within a collaborative are sharing information that affects competition, which may amount to a breach of Chapter 1 of the CA98. Additional considerations may apply under the merger control regime set out in the Enterprise Act 2002 where providers are coming under joint control.

To avoid competition law being a barrier to IHOs, the Department of Health and Social Care should liaise with the Competition and Market Authority and, if necessary, use the upcoming NHS reform bill to disapply certain aspects of competition law to the NHS and/or where IHO contracts have been awarded.

The relationship between IHO and neighbourhood health contracts

Alongside IHO contracts, the 10YHP introduces two new neighbourhood provider contracts. The ‘single neighbourhood provider’ (SNP) contract maps onto the primary care network (PCN) population footprint of 30,000-50,000 to deliver joined-up, enhanced neighbourhood care. The second type, ‘multi-neighbourhood provider’ (MNP) contracts, will be used to deliver care across more than one neighbourhood, covering populations of 250,000 or more. Both aim to unlock the benefits of working at scale through joined-up corporate infrastructure, data analytics and quality improvement infrastructure.

IHOs and new neighbourhood contracts should perform different, but complementary, roles: the IHO contract shifting resource towards neighbourhoods and the neighbourhood contracts overcoming fragmentation in the delivery of out-of-hospital care. Mapping SNP footprints to MNP footprints, and then MNP footprints to IHO footprints, will be essential for ensuring coterminosity, so ICBs can set outcomes consistently at all scales.

In some areas, particularly where there is no at-scale primary care organisation, an IHO host provider could sub-contract neighbourhood care through the SNP and MNP contracts within its population. While the expectation is for neighbourhood contracts to start to be rolled out in 2026, the government’s plan is for a small number of IHOs to become operational in 2027.

2.2 Finding the right structure

How could partners come together?

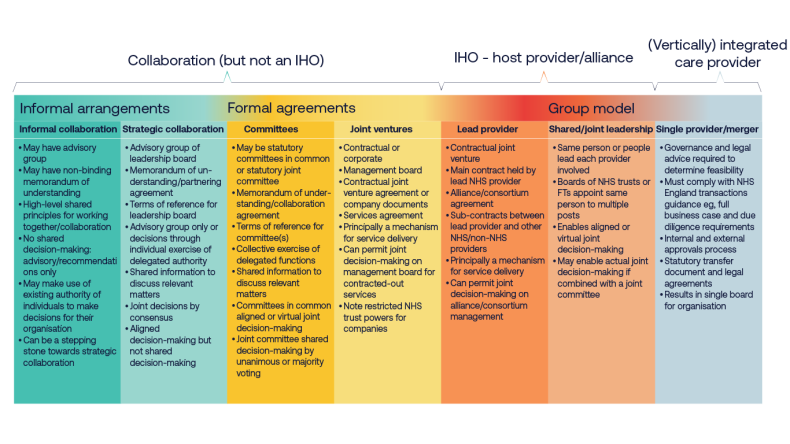

Beyond a contractual relationship, providers across care pathways need some level of structural integration to facilitate collaborative planning and decision-making. Rather than a costly and disruptive reorganisation of the provider landscape, this should be approached in the spirit of evolution, strengthening the arrangements that already exist locally. As Browne Jacobson and the NHS Transformation Unit describe in their report, Collaborative Care, there are multiple approaches to provider collaboration available dependent on local circumstances. These range from statutory committees and joint ventures to lead provider or alliance models or shared leadership (but separate organisations), up to a single merged organisation (See figure 2).

Figure 2

Figure 2. Levels of provider integration, taken from Browne Jacobson and the NHS Transformation Unit, Collaborative Care (2024).

This spectrum is not linear, and in a given area providers may choose to arrange themselves using a range of the approaches outlined in figure 2.

For an IHO contract, given that by definition a lead (better termed a ‘host’) provider sub-contracts partners, at a minimum a lead provider model is needed. This could be deepened with shared or joint leadership. Local partners should be empowered to choose the best model based on their local readiness and existing configurations. At its extreme, this could see all the providers become a single merged organisation. The merged organisation would provide all services in house without sub-contracting them. At this stage it will have evolved into an integrated care provider. Reaching this level of integration is not a realistic prospect in the near future for most areas, although it may happen sooner in areas with ‘neater’ provider arrangements where there are a smaller number of care providers and coterminous local authority boundaries.

Mental health providers are already using a collaborative model based on a lead provider to align incentives across multiple providers to de-invest in inpatient care and invest in community-based resources. The provider collaborative model in provision of specialist mental health, learning disability and autism services are established collaborative working arrangements, that have taken on specialised commissioning delegated budgets and functions from NHS England in recent years. Starting with commissioning a small number of specialist services in pilot sites, they have grown to cover all of England and the vast majority of specialist mental health and learning disability provision.

The collaboratives foster greater integration and better relationships between mental health providers, including independent and VCSE organisations where appropriate. In the East of England, the provider collaborative has significantly reduced out of area placements for children and young people. West Yorkshire Mental Health, Learning Disabilities and Autism Collaborative has reduced the number of people admitted to hospital, lowered spending on inpatient care and reinvested savings into community-based services. For further details and case studies see Annex 1.

Who can be the host provider?

A tension exists between who should host an IHO contract versus who could. The 10YHP stipulates only the ‘very best’ new FTs (as defined in annex 2 of the Advanced Foundation Trust guide) can become IHOs, limiting the opportunity to acute, mental health and community foundation trusts. Non-statutory NHS bodies, including primary care providers, are therefore not eligible under existing policy.

While NHS leaders have mixed views about which type of trust (acute, mental health, community, ambulance or mixed) may be best placed to take on the hosting role, there is consensus that the designated provider should be determined locally based on mutual agreement as to which provider is best placed to deliver its functions. The IHO host provider will also need different governance arrangements given its responsibility for population health, not just delivering activity and services (see section 2.3).

“The IHO will need to be led by someone and who that is will vary dependent on abilities and skills in different areas. It should be the organisation that is best placed, not because they are more dominant or involved but because they have the strength to get the alliance working. This will vary across the piece.”

Mental health trust leader.

“There is a need to make sure it’s not an acute-led process and make sure everyone feels they have parity within the relationship. The relationship is not about the lead provider, it’s about equals coming together. The lead aspect is just a reflection of how the money flows.”

Primary care provider leader.

A primary care lead provider could, in theory, offer the most coherent model for integrating physical and mental health services. For primary care to take on such a role, it would need to operate within a statutory framework that enables practices and primary care providers to come together as a corporate entity. Some trust leaders also expressed scepticism about the feasibility of IHOs being hosted by, for example, GP federations, citing concerns around their ability to manage risk and ensure organisational robustness. However, in areas which do have primary care at scale with robust formal governance, risk management and devolved decision-making, these bodies should not be ruled out of becoming IHO host providers in the longer term. GP federations are likely in many places to hold multi-neighbourhood contracts. This may provide them with the opportunity to stabilise the contracting, provide organisational robustness, and to explore NHS body status.

Regardless of who hosts the IHO contract, it will be essential that all parties to the IHO contract are fully engaged and incentivised to partner effectively within the arrangements.

The role of primary care

Leaders across all trusts and ICBs stressed the key role of primary care within the partnership arrangement; the breadth of primary care and not just general practice. Primary care leaders have a strong understanding of local population need, offer clinical leadership and will, in many cases, hold neighbourhood contracts. In the words of one community trust leader:

“If you don’t establish an IHO in a way that includes primary care within the contract, you lose a huge lever to shift the balance of system finances.”

In other models, such as ChenMed in the USA, GPs are employed directly by the equivalent IHO body, reflecting a vertically integrated approach to service delivery. However, the GP partnership model, comprising independent contractor businesses with self-employed GPs, is the main legal framework for delivering NHS general medical services in England. The same applies to many community pharmacies, optometry and dental practices who operate under the independent contractor model. This raises questions around the application of competition law, given that primary care providers, as independent contractors, are not formally constituted as NHS entities. Consideration should be given to whether this issue could be overcome by ensuring practices sit within an at-scale primary care provider, with alignment across SNP, MNP and IHO contracts.

Across England, general practice contracts have frequently been taken on by NHS trusts when practices have faced difficulties or risked closure. NHS trusts have rightly recognised the significant risk to the local health economy if these practices were to close and have intervened to ensure continuity of services. In some areas like Wolverhampton and Chesterfield, NHS trusts have taken on General Medical Services (GMS) contracts, thus directly employing GPs. But this approach is unlikely to become universal – at least not in the near future.

Many GP at-scale organisations have also successfully taken on GMS contracts for practices that have handed their contracts back and successfully managed these services within the GMS envelope. Going forward, these organisations must be empowered to support the stability of practices and, where required, support with the turnaround of practices.

Integrated models designed to support the delivery of GMS should include expertise in operating safely and efficiently within the GMS framework. This can be achieved through strategic collaboration with primary care at scale. Having a strategic partnership with an at-scale organisation could allow the continuity of services whilst returning practices to GP partners if viable and appropriate.

Including primary care provider leadership within IHO arrangements can be challenging due to the fragmented nature of primary care provision across and within general practice, community pharmacy, optometry and dentistry provision. But we are now seeing primary care provider collaboratives emerging across the country. These collaboratives are acting as both a voice and in many cases a provider of at-scale services.

The role of the ICB

In their new strategic commissioner role ICBs will increasingly be expected to commission care around the needs of populations, transitioning away from the existing activity-based model. IHO contracts will be one of the options available to do this. ICBs will be responsible for setting the parameters, outcomes and goals that IHO host providers are accountable to deliver on behalf of the population. ICBs will work closely with local partners including health and wellbeing boards and draw on their population health improvement plans to set these outcomes. They will use their expertise in population-level analysis, working closely with public health colleagues, patients and communities, to understand the priority areas for transformation. They will also be responsible for evaluating the impact of and delivery against that contract.

Currently, resource for primary care digital and analytics sits within ICBs, bar some pioneers like Birmingham and Solihull. However, agile, high-quality analytical capability at place level will be essential for transforming care from a predominantly reactive to a more proactive model. ICBs, alongside regional teams, will therefore need to support IHO host providers to develop this capability over time so it becomes the norm, not the exception.

ICBs will also help foster the conditions in which IHOs can thrive, giving providers the autonomy and operational independence to deliver IHO functions. This will require cultural change and a departure from their pre-10YHP role, which involved greater day-to-day operational oversight.

IHOs will likely see host providers assuming some ICB functions for their population, in line with the model ICB blueprint, which suggests functions will be delegated or contracted to providers over time. In many places this will take several years.

“The most mature ICBs are already exploring how to hand over responsibilities to provider partnerships, recognising that strategic commissioning and operational delivery cannot be effectively managed at the same level.”

Acute trust leader.

Delegation of commissioning from ICBs is currently extremely limited. And ICBs’ timescales for delegating commissioning functions to providers will vary according to providers’ readiness to take on this responsibility – something which is impacted by current operational pressures.

Collaboration with local government

IHO host providers would be accountable for contracting healthcare services for their population. However, given their responsibility for improving population health, they will need to collaborate with ICBs and local government to do this. In the words of an acute leader:

“It’s not an NHS only issue. A competent IHO needs to be leading collaborative working with local government.”

IHO host providers could co-commission services with local authorities, as ICBs do, and IHO contracts could in future include service provision of Section 7A public health functions (following planned delegation of commissioning from regions to ICBs in 2027).

However, there are currently legal barriers to wider collaboration with local government. Mechanisms to pool budgets and delegate functions need strengthening. For example, something akin to Sections 65Z5 and 6 of the NHS Act 2006 for local government would provide an easier mechanism to delegate and share decision-making on health related and public health functions with other public authorities.

Additionally, the National Health Service Act 2006 stipulates that at least 51 per cent of a foundation trust’s income must come from the provision of NHS services. This threshold was originally intended to ensure that foundation trusts remain primarily focused on delivering NHS care. However, this requirement presents a challenge for IHO host providers, which may eventually seek to include services that span across public health and social care within their sub-contractual arrangements. This requirement should be changed to relate to public service income, not specifically NHS income.

Similarly, NHS Resolution’s indemnity schemes would need to be considered given that services may not be only provided by employed NHS staff. As IHOs may take on responsibility for social care and public health services, NHS Resolution’s indemnity remit may need to be broadened. Beyond legal limitations, joint working with local government is still limited and would require drastically improved relationships.

The role of the ‘integrator’

The relationship between the IHO host provider and ‘integrators’ will likely vary. In some areas the integrator and IHO host provider may be separate but complementary. In other areas whether the integrator is a lead provider, it may evolve into the IHO host provider if at an appropriate scale. Some healthcare leaders use the term ‘integrator’ to refer to an existing organisation operating as a host provider, supporting frontline teams by coordinating funding, data, workforce, estates, and other enablers. This role has been articulated in London’s target operating model for neighbourhood health. This integrator primarily hosts the necessary functions to enable neighbourhood working at scale, but in some areas also enables hospital-at-home and urgent community response services and coordinates integrated discharge. The integrator should provide the necessary infrastructure to enable a group of providers to work together in delivering neighbourhood health across multiple neighbourhoods through MNP contracts.

2.3 Reimagining governance

Refreshing FT governance: from an organisation to population focus

The responsibilities of an NHS FT would expand considerably if it became the host of an IHO contract, with the 10YHP confirming that IHOs will be ‘underpinned by… [a] refreshed FT governance model’. This includes new responsibilities for population health management and the sub-contracting of services from other provider organisations. Currently, the governance of FTs focuses on service delivery and organisation performance.

This shift will require alternative governance arrangements that work more effectively across organisational boundaries, can manage higher levels of shared risk and ultimately improve population health outcomes. As one ICB leader put it:

“Even with the best performing FT in the world, they still need to shift their mindset to be a proper integrated health organisation that’s caring for the population.”

Within a more devolved operating model, the legislation and policy on IHO governance should remain permissive, setting broad national principles rather than prescribing specific board or committee structures and processes. Decisions about governance arrangements should be rooted in a deep understanding of local system context, including existing partnership structures and population needs. They should also be treated iteratively based on continuous evaluation and review.

Integrated governance structures

Healthcare leaders believe the provider body overseeing an IHO should include a diverse mix of individuals with varied sectoral backgrounds, skills and expertise. As one acute leader told us: “It would be very difficult to achieve vertical integration without bringing the many partners across the system under one governance banner.” Without such a structure, progress would rely too heavily on individual relationships and good will.

The simplest way of achieving this may be to embed system partners within the host provider’s existing governance structures, for example by appointing representatives directly to the FT’s board. This would be similar to the outgoing ICB ‘partner member’ model. However, some leaders feel it may be necessary for the FT board to delegate responsibility for the IHO to a sub-committee or sub-committees given the responsibility for the IHO will sit alongside the FT’s existing duties to deliver high-quality, safe care – which already represents a significant undertaking. Both options would likely expand an FT’s board and/or committee structures, which may create challenges in meeting the requirement for all NHS trusts to reduce corporate growth costs by 50 per cent.

Alternatively, in areas where a more neutral decision-making platform is preferred, a joint committee could be established between the IHO contract holder and partner providers. This would formally sit outside of the FT but report in through the host providers’ board and committee structures.

In all the options presented, the FT board retains ultimate accountability and must be equipped to provide strong organisational leadership and effective oversight.

Some healthcare leaders proposed a model where the FT acts mainly as the legal host for the IHO contract and funding, with governance led by a separate body with its own legal status and delegated powers. In areas with established large-scale primary care, this could resemble a joint venture or alliance, as seen in Surrey, Herefordshire, and Berkshire. 7

While this model could further separate population health responsibilities from operational pressures, we have reservations about its practical implementation. Placing governance outside the host provider may introduce complex contractual and accountability arrangements. Nonetheless, these models will continue to play a key role in supporting the collaborative partnerships that underpin contractual arrangements (explored further in section 2.2).

Hallmarks of good IHO governance

Although the specific structures adopted will vary locally, leaders from trusts, primary care and ICBs proposed a set of common characteristics of effective IHO governance:

- A robust mechanism for shared decision-making that includes representation from across the health and care system, including at-scale primary care, VCSE organisations and local government (eg. directors of public health).

- Relevant expertise within the governance structures, including in commissioning, population health management and health inequalities, outcomes-based contract management, delivering the left shift and driving system efficiencies.

- A clear mechanism to support collective problem solving and resolve disagreements, with safeguards to protects the interests of smaller system partners.

- Transparent and meaningful local accountability mechanisms that can replace the role of councils of governors, which the 10YHP announced would be removed

- Independent accountability arrangements to identify and manage potential conflicts of interest in commissioning decisions

When designing new governance arrangements to hold an IHO contract, local leaders should consider these criteria alongside wider guidance on good governance. Detailed advice has been provided by NHS Providers.

The sequencing challenge

Robust governance is an essential prerequisite before awarding an IHO contract, given the scale of the risk and complexity involved. As we have described, governance arrangements should be guided by national principles but locally determined, reflecting system configuration, population needs and the contractual relationships underpinning the IHO. This raises an important question: should governance arrangements be established before designating an IHO host provider and determining the contractual form, or vice versa?

Healthcare leaders consistently told us that form should follow function. In practice, this means starting with a clear definition of the IHO’s purpose, followed by its core functions and success measures. Only then should the contractual form be agreed, with the final governance arrangements put in place before the contract takes effect.

However, some form of shared decision-making mechanism will need to exist earlier to ensure that system partners can agree the IHO’s functions and contractual form. Host providers will need to demonstrate that they have, or will be able to implement, suitable governance arrangements to take on the responsibilities described. Healthcare leaders emphasised that initial IHO designation should be based on collaborative leadership capability (see chapter 4), with some concern about how to assess which FTs are best placed to take this forward in a transparent, evidence-based way before formal governance is established.

See chapter 4 for our recommendations to DHSC and NHSE on the wider IHO authorisation process. Given the political pressures to move at pace, we expect a more pragmatic approach to be adopted for the first wave of IHOs.

2.4 Collaborative behaviours and leadership

While policy and system design often prioritise the ‘hard levers’ of contracts, governance and structures, sustainable integration depends on the quality of relationships and the leadership behaviours that operate in the spaces between organisations. Effective collaboration requires individuals across organisational and professional boundaries to have agency to share insight, influence collective priorities, and take shared responsibility for outcomes.

Trust, shared purpose and a collective commitment to improving population health are the foundations of these conditions. Without purposeful investment in relational development, leadership capability and environments that support joint problem-solving, even the most sophisticated governance and contractual arrangements will fail. As one ICB leader noted: “Contracts don’t deliver care – people do.”

In many systems, these enabling conditions are not yet fully established. Longstanding professional and sectoral identities, differing organisational incentives and entrenched cultural norms can reinforce siloed and at times protectionist approaches to decision-making. Strengthening systemic integration therefore requires a deliberate focus on fostering collaborative behaviours, building trust, aligning purpose and embedding the principles of contributory leadership into the way partnerships plan, prioritise and deliver care together.

Towards collaborative leadership

IHO host providers will need to move beyond institutional interests towards a shared, system-wide focus on population health and the delivery of the left shift, reducing avoidable demand for acute and emergency services through proactive, preventative and community-based care. Leadership will need to demonstrate ‘split-screen thinking’, balancing the legitimate operational and financial pressures of their organisations with collective accountability for population health outcomes and system performance.

To enable this, providers must feel supported and trusted to demonstrate the right level of risk appetite to shift resource upstream. This requires a move away from organisational sovereignty towards genuinely collaborative leadership, where system partners have strong levels of trust, co-own challenges, share data and insights, and work together to resolve tensions constructively.

Leadership within IHOs will need to be about convening rather than controlling, creating the space for shared purpose, joint problem-solving and inclusive decision-making. This represents a fundamental shift in mindset from traditional hierarchical leadership to a model of stewardship that operates across organisational boundaries. As one community and mental health trust leader put it, the host organisation must 'wear its contractual responsibility lightly, acting as a steward of partnership rather than a central authority.'

The incoming NHS Management and Leadership Framework provides a timely opportunity to embed these principles. Its focus on system leadership, compassionate management and distributed accountability aligns closely with the behaviours required for contributory leadership. By emphasising collaboration, learning and leadership across boundaries, the framework may help to strengthen the capability of leaders to work in service of the whole system rather than individual institutions.

In parallel, operational and structural barriers to collaboration must also be addressed. These include workforce passporting, single IT sign on, digital operability and data sharing, clinical risk management and incident learning. The host provider will also have to develop a financial strategy that aligns with organisational boundaries and encourages providers to move money between themselves in support of shared goals.

Contracting and sub-contracting will require high levels of trust, transparency and mutual accountability. The form this takes will vary from place to place, but the competencies underpinning convenorship and the ability to work in partnership with the ICB and other providers to define the parameters of the contractual agreement and how it is delivered should be a central part of the IHO approval criteria.

‘Race to the top’

The new contracts outlined in the 10YHP give providers a stronger role in the allocation of resource and the coordination of care. For the first time, this positions providers to play a more direct and influential role in driving the left shift – a responsibility that has traditionally sat with commissioners and NHSE.

This leadership should be perceived and exercised collectively across providers, rather than individually, with many healthcare leaders concerned that IHO status will be treated as a ‘badge of honour’ or a ‘race to the top’. As one ICB leader said: “The public wants safe, integrated care - not competition”, with an inherent contradiction in asking organisations to ‘prove’ who is the most collaborative. If this happens, there is a concern that IHOs undermine other recently developed partnership models, which have started to improve population health outcomes.

There is also a practical implication of this competition. For example, how do you deal with circumstances in which two trusts both want to take on the IHO role in their local areas, or whether the authorisation of one IHO in a place would close off IHO status as a potential route for neighbouring trusts? To ensure relationships are preserved during this process, authorisation decisions and communications will need to be handled sensitively and transparently, while there is a clear convening role for the ICB in managing relationships locally.

Chapter footnotes

- 2. Some leaders reflected that in future the IHO contract could include some of the service provision functions of public health in future. This is explored in more detail in section 2.2. ↑

- 3. Lessons from Systems, (NHS Confederation, 2025). ↑

- 4. Guidance on Assuring Novel and Complex Contracts, (NHS England, 2017). ↑

- 5. NHS Payment Mechanisms for the Integrated Care Age, (NHS Confederation, 2024), p. 49. ↑

- 6. Sir James Mackey, Working Together in 2025/26 to Lay the Foundations for Reform, (NHS England, 2025). ↑

- 7. See annex for a more detailed explanation of the Surrey Downs model. ↑

3. Considerations for the DHSC and NHS England: avoiding risks, navigating authorisation and oversight

3.1 Designating advanced FTs and IHOs

The 10YHP announced that a small number of new IHOs will be designated in 2026, with a view to them becoming operational in 2027. This is expected to involve at least a two-stage authorisation process: first becoming an ‘advanced FT’ and then becoming an IHO host provider (see box 1 for a summary of what we know). While a government-led approach may be necessary in the initial wave of IHO authorisations to meet the government’s deadline of 2026, we believe that, in the future, this process should be initiated by ICBs. This approach will ensure a more informed decision about which model will best meet the needs of local populations, based on ICB and host provider capabilities.

Local NHS leaders are also concerned about a misalignment between the ambition and timescales for ICBs’ and providers’ readiness to effectively take on IHO responsibilities, particularly due to pressing operational, financial and structural challenges. One community leader said:

“There’s a real risk of getting excited about the ‘new fashionable thing’ where everyone runs to be the first, without being properly clear on the substance.”

What we know about the authorisation of advanced FTs and IHOs

The first wave of trusts are expected to be assessed for advanced FT status shortly. Our understanding is that advanced FTs refer to a new status attached to the existing FT framework, as opposed to a new legal form of NHS provider organisation.

- The selection process for advanced FTs will be overseen by a panel of independent members.

- Advanced FT authorisation will be based on excellent delivery on waiting times, access, quality of care, financial management and higher levels of productivity than their peers, as well as a proven track record of, and commitment to, working in partnership to improve health outcomes.

- The NHS Oversight Framework, provider capability assessments and CQC assessments will likely inform the measurement of these areas.

- Advanced FTs will have the opportunity to hold an IHO contract, alongside the freedom to control board composition, strategic autonomy, financial freedom and raising capital.

- The initial criteria include an ability to meet core standards, improve population health, form partnerships with others and remain financially sustainable.

- The first IHOs will be designated in 2026, with a view to them becoming operational in 2027.

- It is not clear whether the independent panel will also oversee IHO designation.

Annex 2 of the draft Advanced Foundation Trust Programme guidance provides detail of what requirements trusts seeking integrated health organisation contracts will have to meet, subject to consultation.

Reward for the best performers or solution for struggling systems?

The 10YHP pitches the ability to hold IHO contracts as a reward for the ‘very best FTs’, rather than a potential solution for struggling systems where an innovative way of allocating funding may have the greatest impact. Healthcare leaders have mixed views on this.

On one hand, it is important that the host provider is in a strong starting position, with an ability to provide assurance to the DHSC and NHS England that it can provide high-quality care and have a strong handle on key operational and financial challenges. In the words of one ICB leader, it must be: “a really mature organisation with a mature set of leaders and really good governance throughout. They need to be financially stable and sustainable and to be able to demonstrate a good record on all other things - other operating issues, quality, etc. They need to start from a strong position and not be an organisation under support.”

On the other hand, given their purpose is to improve allocative efficiency (and in turn financial performance), those with the greatest need (and deficit) could stand to benefit most from the IHO model, potentially adopting a mixed model of high performers and those with greatest need.

Given IHO host provider status will exclusively be a ‘reward’ in the short term, it will be important for the centre to set a longer-term pathway and corresponding support programme that ensures holding an IHO contract become an opportunity available to all. NHS England’s support programme should extend to both the first wave of IHO designates in 2026/27 as well as leaders (including from ICBs) in more challenged systems who are interested in holding an IHO contract in the medium term. Otherwise, there is also a risk that performance variation and inequalities are exacerbated.

Many NHS leaders view holding an IHO contract as an end state to work up to, not an immediate or short-term endeavour. As outlined in section 1.4, there are alternative models that would also allow systems to make progress towards more integrated and cost-effective care and may help build the foundations needed to hold an IHO contract in the future.

Capability should trump operational performance

The government’s definition of ‘high performing’ trusts and the competencies needed to host an IHO contract must align. This criteria should include the suitability not just of the host provider, but also the capability and performance of the ICB and other providers within the system. Both organisational and system capabilities should be the most important consideration in assessing IHO readiness.

Designating the host provider

Candidate FTs should have a strong track record in collaborative and integrated working. Performance in service delivery at a single point in time might not be the best indicator of readiness to run, contract and manage a wide range of services to improve the health of a geographically defined population.

Despite this, several local leaders feel that the approach being taken nationally to the host provider role has focused more on the highest performing organisations, regardless of the wider system and collaborative working. These tend to be larger acute and specialist providers, rather than those necessarily most capable of taking on the role. Some worry that the requirement to first achieve FT status may not result in the right organisations becoming the host provider. In the words of one acute trust leader:

“It could be a lot more powerful if done on the basis of co-design and collaboration. The decision should be based on having the infrastructure and partners and ability to recognise the need for partnership working.”

Local leaders described a range of competences they thought would be needed to be an effective IHO host provider. These could form the basis of the authorisation process involved in becoming an IHO.

- Financial and organisational maturity

- Maintains financial balance.

- Shows organisational robustness, including dispute resolution and shared decision-making.

- Governance and risk management

- Operates within a statutory framework that enables corporate formation and robust governance.

- Capable of managing risk and making strategic decisions at scale.

- Understanding of commissioning

- Demonstrates a clear grasp of the commissioning cycle and the ability to engage effectively with commissioning processes.

- Has the ability to manage a range of contracts, guided by a commitment to improving population health outcomes, while managing any conflicts that arise based on organisational interests.

- Collaborative leadership

- Demonstrates strong backing from system partners and a proven track record in partnership working and prioritising place-based outcomes over organisational interests.

- Provides infrastructure to support mature, collaborative decision-making and conflict resolution.

- Population health capability

- Demonstrates expertise in population health management and addressing health inequalities.

- Actively engages in prevention and left-shift strategies aligned with the 10 Year Health Plan, including evidence of redirecting resources from acute care into primary care, community, mental health services, including VCSE services.

- Access to and ability to use comprehensive data for population health analysis.

However, the current National Oversight Framework (NOF), provider capability assessment and CQC’s assessment framework do not adequately assess these capabilities. Some trust leaders are concerned that their league table position will prohibit them from exploring an IHO in their area. This means an updated or bespoke authorisation process will be required by the time the first IHOs are designated. This may follow a phased or gateway approach with multiple stages.

Most healthcare leaders believe that many of these competencies require more development – particularly to meet the core requirements for delivering population health management. It may also be necessary to transfer staff from ICBs to the host provider, particularly so they have sufficient understanding of the commissioning cycle.

ICB capabilities

ICBs play a vital role in commissioning IHO contracts, which means ICB capabilities must form part of the IHO authorisation process. This includes their ability to discharge their four core functions as defined in NHS England’s model ICB blueprint and strategic commissioning framework. In our State of ICSs report, ICB leaders told us they feel confident in fulfilling their first two new functions: understanding local context and developing a population health strategy. ICBs already have varied and comprehensive ways of understanding their populations and are already responsible for producing five-year strategies and implementation plans. But they recognised that organisational development and upskilling are required to fulfil their payer, market-shaping and impact-evaluation functions.

ICBs capabilities in the short term will be impacted by reorganisation, following the requirement to reduce their budgets by 50 per cent. And with ongoing uncertainty about the future of some of their other statutory functions, ICB leaders are concerned about investing in and building strategic commissioning capability while maintaining the capacity and capability needed to meet their core statutory obligations. The NOF and capability assessments do not apply to ICBs in 2025/26 but will do so from 2026/27. Without a formal ICB oversight regime in place, it is difficult to see how this could be assured in the short term. Before the first IHO host providers are designated in 2026, this should be addressed in a robust and transparent manner so that IHO designation is conducted in an evidence-based and transparent manner.

3.2 Accountability and oversight

The health and care system needs a simple and effective system operating model, where every part of the system is clear on its purpose, what it is accountable for, and to whom. Due to the integrated nature of IHOs, there is a heightened risk of overlapping responsibilities and shared decision-making arrangements leading to blurred lines of accountability.

If the host provider is ultimately to be held accountable, then careful thought must be given to how this is managed alongside accountability for the provider's own service delivery responsibilities, including metrics assessed by the NOF and CQC assessments. This is essential to avoid creating an overly complex or burdensome reporting system and to prevent competition between organisational interests and system-wide goals.

The host provider will also need clear lines of accountability given the level of financial risk they will hold on behalf of their local population. This includes clarity from the government and ICBs about the outcomes they are expected to deliver. Over time, there should be a shift from process compliance to a small number of high-impact and measurable health indicators that are linked to population health.

“If you have a capitated budget, formal accountability and associated enforcement mechanisms for the population served are necessary. I don’t think accountability from a trust directly to the Secretary of State is going to work. It’s very different to hold someone to account on deterioration in people’s health.”

ICB leader.

IHO oversight is likely to be tied to the existing oversight and regulatory regime, as opposed to a new legislative framework. As an extension of the advanced FTs, IHO host providers will presumably remain under the NHS provider licence. Some healthcare leaders questioned the ability of effectively overseeing IHO host providers from the centre, especially given current provider performance challenges.

“In a world in which nobody's got sufficient money or they're not functioning efficiently enough to manage their money I think it's very, very difficult.”

ICB leader.

DHSC will need to decide whether there will need to be a deauthorisation process or contract transferral process for advanced FTs and IHO host providers that experience major performance or financial issues, or which fail against other criteria. When a local health system is designed around a provider, it is not a simple matter to move to a different arrangement if things go wrong.

Clear lines of oversight

ICBs and regions

According to the 10YHP, IHOs will be overseen ‘in a proportionate, rules-based way by their NHS region.’ Meanwhile, the strategic commissioning framework confirms that ICBs will provide ‘robust oversight’ of host providers through their contractual relationship. This includes holding them to account against the outcomes they have commissioned them to achieve for their population, as is the case for other providers including those holding neighbourhood contracts. The IHO contract should also include a regime for dealing with failure, including step-in arrangements with sub-contractors when the main IHO contract fails. There needs to be sufficient clarity and distinction between ICBs’ contract management role and NHS England/DHSC’s regulatory and performance management functions to avoid duplication and hindering IHO progress.

It is not year clear that regional teams have the capacity and capability to discharge this function, given the extensive range of other functions also set out in the model region blueprint. Unlike the model ICB blueprint, the model region does not clearly specify what functions are new, existing or will be stopped or transferred elsewhere, begging the question: will they have capacity to oversee and support systems developing IHOs?

The CQC

It is unclear what role the CQC will play in assessing IHO host providers and sub-contractors of care, rather than just providers. Given they are still undergoing a major recovery and transformation process, concerns will likely remain about whether the CQC is yet in a position to take on this new responsibility or develop a novel way of assessing this different way of working. But robust regulation will be essential to ensure IHO host providers are effectively discharging their functions.

3.3 Aligned incentives

Regulatory and financial incentives must align to support integration and partnership working, including developing local community and place-based services. However, healthcare leaders are concerned that the short-term political focus on recovery at the level of individual organisations will undermine the partnership working required to hold IHO contracts. National and regional oversight must encourage a shift from sector-centric thinking to a whole-system approach rooted in population health management and outcomes. This requires a more future-facing oversight regime that avoids punitive measures and incentivises collaboration.

Authorising IHO host providers based on FT status, combined with an oversight regime that relies on organisational league tables encourages a return to organisational sovereignty and competition, not collaboration. The 10YHP implies that both competition and collaboration are king. But can the NHS coherently hold two organising principles?

Until recently, trusts were increasingly taking on stretch targets or ‘load balancing’, which involved them carrying higher risk to help improve system-wide operational and financial performance. We have significant concerns that organisations will be less willing to do so when judged individually and competitively. For instance, the NOF’s financial override led to downgrades for numerous previously high-performing trusts, discouraging the kind of collaboration described. Similarly, abolishing system control totals for all providers removes a key mechanism for shared financial responsibility, reinforcing individual organisational success or failure.

“By taking that away, we’re reinforcing the organisationalness of the financial success and failure of boards and this may not result directly in the sort of system responsibility you need to be an IHO.”

ICB leader.

To give IHOs a chance to succeed, there must be a transformative move away from the current command and control culture, which combines central routine performance management, guidance and political intervention.

A strong emphasis on individual organisations also makes it harder to shift from recovery to transformation. While local leaders generally understand the desire to concentrate efforts toward short-term operational priorities and recovery, they are increasingly worried that the current balance between recovery with reform will undermine progress toward the government’s three shifts and the viability of IHO contracts.

The longer-term commitment to focus on outcomes and effectiveness alongside access and value for money over time is welcome. But if IHOs are to flourish, the government cannot wait until the system has recovered before making necessary changes. As an acute leader put it:

“If the oversight framework is genuinely interim and the FT assessment and future framework goes back to an operating model that promotes collaboration and integration then I can support the idea of short-term pain for long-term gain.”

If IHO performance is to be judged against the Medium Term Planning Framework and the NOF, both will need to evolve in lock step with the roll out of IHOs to ensure that they incentivise delivery of the left shift, increased allocative efficiency and improved population health outcomes. The current metrics and targets in each are reminiscent of an activity-based model. Without this alignment, we remain concerned about how the current model can support or meaningfully measure the success of IHOs.

3.4 National support and backing

Local leaders want aircover from the centre to make difficult decisions, take calculated risks and to see through a significant transformation process over several years. IHOs will only succeed as a model in an environment where local leaders feel able to radically transform the way they operate. Once an IHO host provider has been designated, the DHSC and NHS England must sustain support for local leaders to deliver what will inevitably be a complex, multi-year transformation. This will require political and policy stability.

Those involved in the previous vanguard programme expressed frustration that earlier attempts were derailed, in part due to shifting government priorities. They described a centre that became less willing to make difficult decisions and a failure to provide local leaders with the backing they needed to implement the plans that had taken considerable time and resource to develop.

As Lord Darzi stated in his review: ‘Constant reorganisations are costly and distracting. They stop the NHS structures from focusing on their primary responsibility to raise the quality and efficiency of care in providers.’

Recommendations

In the upcoming Model IHO Blueprint, NHS England should:

- Empower ICBs and local provider partners to decide whether and how to establish and hold IHO and neighbourhood contracts and what population size they should cover.

- Establish a transparent process to IHO authorisation that considers the host provider board’s capability to manage population health, effective collaboration agreements, risk-sharing arrangements and ICB capability.

Outside of the blueprint, NHS England should:

- Update the NHS Oversight Framework and financial and performance metrics for 2026/27 to support a transition from metrics focused on organisational recovery to those that better incentivise transformation and collaboration between organisations. A new set of metrics should be in place by the time the first IHOs become operational in 2027. It is critical to the success of IHOs that national incentives are aligned toward collaborative behaviours and leadership.

- Support and resource the development of ICBs’ and IHO host providers’ strategic commissioning skills and capabilities, making any changes to policy and guidance needed to allow ICBs’ to delegate some of these functions to IHO host providers over time.

The Department of Health and Social Care should make the following legislative changes:

- Ensure high standards of probity and conflict management, by liaising with the Competition and Market Authority to explore compatibility with IHO contracts and, if necessary, assessing whether legislative reform is desirable.

- Amend Section 44 of the National Health Service Act 2006 to redefine foundation trusts’ 51 per cent income threshold in terms of ‘public sector’ funding rather than strictly ‘NHS’ funding, to enable social care and public health services to be included in IHO contracts.

Conclusion

IHOs can improve health outcomes and allocative financial efficiency by aligning incentives for providers through a lead or ‘host’ provider model, delivering a better and more cost-efficient service for patients and taxpayers. IHOs are one of several models available to local leaders to integrate care and improve population health at a lower cost. For areas eligible, IHO contracts can be part of the answer to fixing the NHS and putting it back on a sustainable footing.

To become an IHO, a foundation trust will need a capitated contract, a lead provider structure, governance focused on improving population health and to demonstrate collaborative leadership and behaviours. As such, all local providers and the ICB should agree to an FT taking on an IHO role. Local provider and ICB leaders believe few providers, if any, will be ready to take on such a contract immediately, as they represent a significant change to how services have historically been contracted. In contrast, every area will hold neighbourhood provider contracts in the immediate future.

There are tensions between what is required to foster the collaborative behaviour which local leaders say is necessary for IHOs to succeed, and existing national policy. This includes performance oversight and league table metrics focused on individual organisational activity and sovereignty rather than system working, financial oversight of individual organisations rather than systems collectively (system control totals), an existing FT regime focused on competition not collaboration, and the abolition of ICB partner members when IHO host providers may need partner member equivalents in their FT governance. Meanwhile, the purpose of IHO contracts - to deliver financial improvement - is at odds with restricting IHO host providers to only the best performing systems and providers. This also risks increasing performance variation.

As NHS England develops a model IHO blueprint, it will need to address the respective roles of ICBs and regions in oversight of IHO host providers; regional teams’ capability and capacity to do this; the future role of the CQC; and aligning the FT status approval status and National Oversight Framework with the collaborative behaviours required of all parties to an IHO contract. The NHS Confederation proposes six recommendations to the Department of Health and NHS England to support the evolution of IHOs.

While there is much work still to be done to hold IHO contracts, and some areas will need to wait longer than others, IHOs can become a crucial part of fixing the NHS. The NHS Confederation and our members stand ready to give them the best chance of success.

Annex 1. Glossary and research aims

Annex 2. Learning from past experiments with accountable care

As mentioned in the introduction, there have been various international and domestic attempts at accountable care. All vary and will not be able to be directly transplanted into the NHS system, but they can provide useful guidance on the journey to holding IHO contracts.

Annex 3. Holding an IHO contract: prompt questions for local NHS leaders

The below questions are intended to prompt local discussion about whether an IHO is the right model to approach based on local arrangements and population needs. The questions are set out in sequential order and could be used, for example, to frame a group discussion or board meeting on each sub-topic.

About Browne Jacobson

Browne Jacobson is a leading UK and Ireland law firm with international reach working in partnership with its clients. The firm provides pragmatic advice and creative solutions-driven support, enabling clients to focus on what matters to them. Leveraging its national and international reach, its lawyers advise a diverse client base including:

- Corporates – from entrepreneurs and SMEs to large UK and international companies

- Insurers and financial services businesses

- NHS bodies and independent healthcare businesses

- Education organisations

- Central and local government and other public bodies

The firm supports, influences, and impacts positive change across business and society by connecting and improving outcomes for every person, community, and business it serves. Its focus on well-being and individuality alongside its commitment to social mobility, diversity and inclusion ensures all its people can thrive.