Reforming financial flows: lessons from systems

Key points

Current financial flows are a barrier to delivering NHS reform and financial sustainability. The 10 Year Health Plan has set out the need for payment reform and the requirement for integrated care boards, as strategic commissioners, to design and implement innovative payments mechanisms.

While the vision outlined in the 10 Year Health Plan is the right one, implementing these new financial flows will challenge long-established principles and ways of working in NHS finance, requiring a shift in mindset across the whole sector.

NHS leaders previously identified outcomes-based payments for patient pathways or populations as a key area for local experimentation to reform financial flows. The NHS Confederation has been working with a small group of integrated care systems (ICSs) to develop their own local approaches to outcomes-based payments.

To support learning in ICSs, we have set out guidance for developing outcomes-based payment mechanisms as well as three case studies that demonstrate different approaches:

A lead provider model with a mix of block and outcomes-based payments in Oxfordshire.

An integrator model with a population-based risk-sharing agreement in Germany.

A prime contractor model with a block contract and monitoring of outcomes through contracts in Bedfordshire.

We also highlight ongoing work in ICSs to develop financial flows for target populations, ranging from outcomes-based contracts for patients at the end of their life to whole population contracts across a place.

Simplicity is key.

Take a population-based approach.

Engage stakeholders and bring partners with you.

Start with the data you have.

Align incentives across providers.

With the right tools and support from the centre, healthcare leaders can reform financial flows to deliver value-based care that improves the lives of patients, staff and clinicians while ensuring taxpayers’ money is used most effectively.

Introduction

Reforming financial flows is crucial to delivering the ambitions of the 10 Year Health Plan and realising integrated care boards’ (ICBs) role as strategic commissioners. There is a clear consensus that current financial incentives are a barrier to shifting to a more preventative and empowering model of care. The Hewitt review identified that current approaches are not driving ‘value-based healthcare’. More recently, the Darzi investigation concluded that ‘hardwiring financial flows’ is needed to lock in the shift to care closer to home, when the data shows that resources have been flowing into hospitals despite the intended policy direction to boost capacity in the community.

Currently, taxpayers’ money is used to pay for individual NHS and social care services separately in a way that fragments the existing model of care. Often, commissioners pay for effort – such as the number of appointments a clinician delivers – rather than what is best to improve patients’ health and experience. This is bad for staff, who feel exhausted trying to provide ever more care; bad for patients, who feel shunted around the system and do not get the best care; and bad for taxpayers, whose money is spread ever more thinly for ever more stretched services. This cannot go on.

The NHS Confederation previously considered opportunities to reform the payment system to incentivise allocative and technical productivity and ensure financial flows support integrated care. We identified developing both outcomes-based payments and risk-weighted capitated payment mechanisms for specific pathways or populations as a key area of opportunity for ICSs. Linking payments to outcomes in healthcare is not new. But there is an increased need to implement new approaches and share learning to deliver better care for populations and manage rising demand for health and care services. In a speech in September 2024, the Secretary of State stated that ‘too many parts of the NHS are now paid for effort, not for outcomes. That has to change.’

Developing innovative payment mechanisms is also a core element of ICBs’ function as a strategic commissioner, as outlined in the model ICB blueprint. ICBs must deliver their role through payer functions and resource allocation, with contracting and payment mechanisms as key pillars. The model ICB blueprint specifically highlights ‘negotiating and managing outcome-based contracts’ and ‘designing incentives and payment models to improve equity, efficiency and productivity’.

This aligns with the NHS Confederation’s vision for strategic commissioning, in which the commissioner seeks to proactively address their population’s health needs, shifting resources upstream, commissioning whole pathways for population cohorts and achieving better value by focusing on outcome measures.

The 10 Year Health Plan clearly sets out a mandate for the health and care sector to change its financial flows. It commits to payment reform, from changing tariffs for urgent and emergency care to developing a ‘year of care’ tariff and working towards population-wide budgets. It recognises that changing financial flows is a key enabler to delivering a neighbourhood health service; without better alignment of financial incentives our model of care will not shift towards more preventative care in the community. It also states that ‘the very best NHS FTs [foundation trusts]’ will be able to ‘hold the whole health budget for a local population as an integrated health organisation (IHO)’ using ‘capitation-based contracting’.

Between July 2024 and April 2025, the NHS Confederation convened a small group of ICS leaders in a series of sessions facilitated by Nick Hicks, senior strategic adviser at the Department of Health and Social Care, to support the development of outcomes-based payment mechanisms for target populations.

This report shares the learning and case studies from these workshops to support NHS leaders across the country as they design and implement new payment mechanisms. This will be particularly relevant to ICBs in their role as strategic commissioners.

AstraZeneca has provided funding for the workshops and report via a sponsorship agreement. AstraZeneca has had no editorial input into this report.

Delivering the 10 Year Health Plan

The 10 Year Health Plan announced key reforms to the NHS payment system, which healthcare leaders have been calling for. Most notably, it set out that:

‘we will use… financial incentives to enable investment in better outcomes, not just into inputs and activity. Resources will be tied to outcome-based targets, which all commissioners and providers will have a responsibility to help meet.’

In the next few months, NHS leaders will be working with the government to develop and implement its proposals, including moving towards more best practice tariffs, incentives for clinical teams, ‘year of care’ payments, reforming payment of urgent and emergency care and payments linked to patient experience. In April 2026, a new NHS Payment Scheme is due to set rules for payment mechanisms and will be updated to reflect the 10 Year Health Plan.

This is accompanied by a focus on longer-term financial planning supported by multi-year budgets and eliminating financial deficits.

Financial flows cannot be changed in isolation and should be supported by the right structures and accountability frameworks. in conjunction with payment reform, new neighbourhood contracts, as well as the potential for foundation trusts to become integrated health organisations (IHOs) which hold population budgets, will need to be developed. This proposed new system architecture is the first opportunity since the purchaser/provider split in 1991 to incentivise providers with population-based outcome measures.

Changing the financial architecture of the NHS is possible. It was done in the early 2000s and can be done again to implement the vision set out by the government. Now is the time to learn from the past, support commissioners and providers who are already delivering reform at pace and spread good practice and learning across the country. The future of the NHS depends on it.

What are outcomes-based payment mechanisms for populations or pathways?

Outcomes-based payment mechanisms financially reward providers for improving the health outcomes of a given population, not just for the volume of activity. In doing so, they incentivise earlier and more cost-effective healthcare interventions and reduce more costly downstream interventions. This is also known as allocative efficiency.

According to the International Consortium for Health Outcome Measurement (2013), an outcome is ‘The results people care about most…including functional improvement and the ability to live normal, productive lives.’ Linking outcomes to payments in healthcare has a long history, for example through the Quality and Outcomes Framework in England.

Outcomes-based approaches to contracting can span whole population groups and multiple organisations or focus on a single service or patient and they can differ in complexity. Across all different scenarios, providers and commissioners will grapple with setting the right outcomes and incentive structure but are likely to start where data and costing is most available. For example, The Strategy Unit has set out an example of what an outcomes-based contract for elective knee replacement might look like.

ICBs and their partners, aligned with the four core purposes of an ICS, are looking at tying allocation of resources to outcomes on a wider scale. Many ICSs have already developed system-wide outcomes frameworks and are implementing new contracting mechanisms to support integration.

In practice, new payment mechanisms will be crucial to shaping these complex systems. This means changing incentives alongside infrastructure and service delivery with providers, commissioners and clinical leaders all having a key role to play.

Linking payments to outcomes is a core element of outcome-based commissioning, which aims to ‘incentivise providers to collaboratively produce integrated services capable of delivering the outcomes that matter to their population, reducing duplication and waste.’ The Health Foundation highlights five components to this:

- A focus on populations.

- The use of outcomes that matter to those populations.

- The use of metrics and learning to monitor outcomes.

- Performance incentives and risk-sharing.

- Coordination of delivery across providers.

The NHS Confederation previously identified some of the enablers, risks and mitigations for outcomes-based payments for pathways.

How might we design and implement them?

Each system or organisation should take its own approach to designing and implementing new payment approaches, adapted to its local context, priorities and ways of working. The table below sets out guidance for developing an outcomes-based payment model within the wider commissioning approach.

What are the different existing models available?

The following three case studies are examples to draw on, rather than an exhaustive list of models and include relevant resources to understand the payment models in more depth.

Case study: Oxfordshire care for people with serious mental illness

Context and population

Mental health services in Oxfordshire were delivered across nine providers and commissioned through 18 contracts, mostly as block payments. Effective and innovative pathways were developed but patients still experienced fractured services and contracts were measured on process, not impact. In 2013/14, Oxfordshire Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) was also in a challenging financial position, with significant savings to make. Mental health spending was set to grow exponentially if nothing changed.

Oxfordshire CCG developed and implemented an outcomes-based contract, which included a range of mental health services, to deliver more integrated and preventative mental health provision that provided better value for money. It originally ran from 1 October 2015 to 31 March 2025. An updated contract was awarded to Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust as the lead provider on 1 April 2025, running for ten years.

Payment model

The total payment comprised of a block contract (80 per cent of the funding), an outcomes element of 10 per cent and then a gain/loss risk sharing element of 10 per cent.

The commissioner allocated funding to a lead provider, who was then able to allocate funding to other providers and spend the funding on care for service users. It included a gain/loss funding risk sharing arrangement between the lead provider and the commissioner.

Outcomes and indicators

Outcomes were developed with people with serious mental illness and relevant stakeholders and measured through key indicators 1 . Weighting was adjusted according to each outcome and over time, with a gradual move to cover the whole range of outcomes.

For example, one agreed outcome was that people will improve their level of functioning. One indicator was the percentage of people who were still discharged after six months.

Data on outcomes was collected and assessed. When pre-agreed targets are achieved, specified additional funding was released to the lead provider and could in turn be shared with a subcontracted provider, aligning the financial incentives for these providers.

Commissioners made decisions in the following areas:

- The overall percentage / value of the total annual contract value that is ‘at risk’ through the incentivisation.

- The weighting between each of the outcomes and for each indicator within an outcome.

- The weightings between ‘good, improved and excellent’ where appropriate.

- The speed at which each indicator and the incentivisation takes effect.

Results

Initial evaluation indicated that by year three, 14 out of 16 outcome targets had been achieved. Feedback from patients and stakeholders indicated an improvement in partnership working across services and improved physical health monitoring but an ongoing challenge with accessing services at the right time.

Case study: Healthy Kinzigtal Integrated Care

Context

The German healthcare system, which is insurance-based, is fragmented and does not incentivise partnership working between providers or preventative healthcare. This means patients often experience unnecessary activity, longer waiting times and a lack of communication.

Following national policy changes to support integrated approaches, a population-based integrated care system was developed in the Kinsig valley, in south-west Germany.

Covering a population of about 31,000 people, the Healthy Kinzigtal Integrated Care System aims to improve population health by improving integration among providers and supporting people to better manage their own health.

Payment model

The regional management company (Gesundes Kinzigtal GmbH), which acts as an integrator, is a partnership between a physicians’ network in the Kinzigtal region (Medizinisches Qualitätsnetz—Ärzteinitiative Kinzigtal) and a healthcare management company (OptiMedis AG). It has set up a shared savings contract with the two statutory health insurers that cover the area. Providers still receive reimbursement payments but Gesundes Kinzigtal GmbH reimburses for some additional services to improve quality of care, such as comprehensive check ups.

Savings are made through the difference between the total actual cost of care for that population and the weighted average cost nationally (cost norm). The savings are then shared between the integrator and the health insurers.

Interventions

Alongside an incentive for providers to provide more preventative care, Gesundes Kinzigtal implements a set of specific programmes targeted at different sets of the population, from healthy individuals without health problems to patients with disease progression and high-cost patients. This ranges from training in health literacy to healthy weight and blood pressures programmes.

Results

Ongoing evaluation had demonstrated an overall health gain, including improved provider satisfaction and patient experience, improved population health (Gesundes Kinzigtal members live on average 1.5 years longer relative to a control group) and reduction in the per capita cost of care.

From 2007 to 2018 the total cost savings margin for the participating health insurance funds was € 53.1 Mill (net € 18.2 mill.).

Case study: Bedfordshire MSK contract

Context

Musculoskeletal (MSK) conditions affect one-in-ten working-age people nationally, accounting for about 16,000 in central Bedfordshire. The Bedfordshire Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) had identified challenges for provision of care for patients with MSK. These included the fragmentation of services worsening patients’ experience of care, complexity in management of over 20 contracts, unwarranted clinical variation in activity and an outdated model of care based in hospital, instead of the community.

On 1 April 2014, Bedfordshire CCG awarded Circle Health a contract to provide an integrated MSK service for Bedfordshire patients. It aimed to provide high-quality care and improve outcomes for patients while maximising use of resources.

Payment model

This is a ‘prime contractor’ model where Circle MSK was responsible for delivery of MSK services across the whole pathway, including an integrated provider hub and community physiotherapy, podiatry, MSK assessments and secondary care.

The contract value was block-funding based on the total cost of all MSK-related activity, regardless of care setting, and was initially set based on the outturn expenditure of MSK services in 2012/13.

The CCG monitored Circle MSK on a regular basis on a range of outcome measures.

Outcomes and indicators

Existing MSK patient outcome measures were used as part of the contract management. This included discussing behaviour and lifestyle changes (Making Every Contact Count), assessing disability in patients undergoing hip/knee replacement and assessing changes for patients with neck and back pain.

Results

Evaluation of the contract demonstrated a reduction in waiting times for treatment in the community, an increase in the proportion of MSK delivered in the community between 2014 and 2017 and a reduction in secondary care referrals and surgery since 2014. This was accompanied by a reduction in unnecessary first outpatient appointments and a reduction in unnecessary trauma and orthopaedic procedures.

Analysis of MSK expenditure showed the contract value was below expected costs and providing value for money, although comparison before the contract is not comprehensive due to lack of activity-based data for some services. Management of over 20 contracts was also replaced with management of one contract, which created better value for the CCG.

Bedfordshire, Luton and Milton Keynes ICB is currently seeking re-procurement for the provision of MSK services which is expected to go live from December 2025 for ten years.

What reforms are ICSs already trying to deliver?

ICBs and their partners have been working on new payment approaches as they develop new models of care for target populations.

Bristol, North Somerset and South Gloucestershire (BNSSG) ICS

Context

The BNSSG system has developed and adopted Healthier Together 2040 as a needs-based approach to whole-system redesign of health and care. The aim is to improve healthy life expectancy of targeted cohorts of the population who currently are living with the poorest health and driving current and future demand. Starting with the working-age population living with multiple health challenges, they are designing new models of care to implement and commission to improve outcomes for these populations and develop payment mechanisms to support them. The ICS already has a system-wide outcomes framework, with an overall goal to improve healthy life expectancy.

Population cohort

For this project, BNSSG is first focusing on a population cohort of about 5,300 people aged 20-to-64 who have three or more long-term conditions from a shortlist of hypertension, diabetes, anxiety, depression and chronic pain. This group is projected to grow by 50 per cent in the next 15 years, under the assumptions of the local Dynamic Population Model. Most people in this group live in deprived areas and their ability to manage their health is significantly impacted by their living and working conditions. In addition to this cohort, there are 38,000 people in wider at-risk groups where there is a prevention opportunity to delay or prevent further deterioration in health. This cohort is the third highest in terms of emergency hospital visits and long-term care needs, which is an indicator that their current healthcare system is unable to adequately support their health and wellbeing. Furthermore, local modelling suggests that about a half of this cohort are expected to be living and in an increasingly frail condition in 15 years’ time.

Outcomes

A set of target outcomes for this population cohort have been codesigned. These include increasing the age of onset of a second long-term condition, reducing the number of days interacting with health services due to urgent needs, people’s functional ability, motivation and self-reported quality of life.

Model of care

Working with communities and stakeholders through a series of workshops and focus groups, an outline model has been developed.

It is a neighbourhood-based model of care for working-age people with multiple health conditions, combining consistent core features across all postcodes with local tailoring to address community needs and reduce inequalities. Centred on personalised wellbeing and health plans, people will be supported by an integrated, multi-professional team that takes a trauma-informed, relationship-based approach, linking clinical care with wider wellbeing support such as housing, employment and financial stability.

Access will be flexible through community hubs, outreach and digital tools, with proactive support offered at key life moments to prevent crisis. Over time, this model aims to reduce unplanned service use by providing holistic, preventative care, easing system pressures while enabling GPs and specialists to focus on those with the greatest need.

Workforce development will prioritise relational skills, digital capability and care coordination, embedding a culture of person-centred, relationship-based care across the system. Ultimately, the model seeks to shift from fragmented, reactive provision to proactive, integrated neighbourhood care that improves outcomes and reduces inequalities, while remaining scalable and affordable.

Next steps

They are now assessing what financial flows could enable these new pathways. In the short-term, they are aiming to bring together existing primary care and community financial flows focused on care coordination, digital self-management and social prescribing. The next round of design will also focus on what it would require to deliver the model set out and what impact it could have. All of this will inform the development of a year-of-care payment structure. The ICB is also currently considering how to move to population-cohort-based payments at system and at place level as a mechanism to shift resources. They have a linked dataset which includes primary, secondary, mental health, urgent care and social care flows with a three-year average of data to help them understand how people use services and track outcomes.

Leeds Place – West Yorkshire ICS

Context

Leeds has a longstanding place-based partnership with two overarching goals of reducing preventable unplanned care utilisation across health settings and increasing early identification and intervention. It has a track record of delivering innovative programmes such as Home First. Leeds has an identified population cohort, outcomes and strong relationships but needs support in designing and implementing new incentives and changing financial flows, which are a barrier to integration.

Population cohort

The partnership runs a Neighbourhood Proactive Care programme, one element of which focuses on a patient cohort of people at the end of life or living with severe frailty in Leeds who go into hospital each year with respiratory disease (about 2,000 people).

Model of care

It has identified several potential interventions to improve care for that cohort and move care into the community around proactive care, out-of-hours support, co-ordination of existing offers and clear care planning. Most of the interventions will be delivered by primary and community care providers, starting with two primary care networks before considering if the evidence base supports roll out of the model across Leeds.

Objective

The partnership wants to reduce the amount of beds days for end-of-life patients with respiratory disease. Patients at end of life / living with severe frailty who are hospitalised for respiratory disease account for approximately 20,000 bed days a year. Improving the quality of life for people and their carers and creating the conditions to enable the workforce to feel they can support this population as effectively as possible through more joined up care are key outcomes at the heart of this project.

Financial flows

Using COPD as a proxy for respiratory issues, the partnership is estimating the resources currently supporting people at end of life with respiratory issues. Excluding hospice care, financial flows for this population are split across:

- the ambulance service (999 calls, NHS 111 call)

- Leeds Teaching Hospitals’ acute services contract (A&E attendances, elective and non-elective spells, outpatients)

- NHS community services and Better Care Fund (community nursing and therapy contact)

- primary care commissioning (GP appointment and out of hours contact).

Next steps

The ICS is looking to do further analysis on costs and contract, to start building a picture of how new financial flows could support shifting care closer to home for this population.

Rochdale – Greater Manchester

Context

Heywood, Middleton and Rochdale is one of ten place-based partnerships in Greater Manchester ICS. Its place lead is also the chief executive of the local authority and deputy place lead is the director of adult social care. Its work as a partnership predates the establishment of ICSs and brings together partners across the NHS, local government, patient voice and the voluntary sector. By 2030, it expects to see not only an increase in its overall population but rising ill-health.

Since 2019, it has been developing a Local Care Organisation (LCO) to deliver its strategy. Led by the Northern Care Alliance NHS Foundation Trust as the lead provider, it facilitates integration of services and supports partnership working across providers and commissioners. It includes Greater Manchester ICB, Rochdale Borough Council, primary care, the voluntary sector and Pennine Care Foundation Trust.

Population cohort

The LCO is responsible for promoting the health of the entire population of the Heywood, Middleton and Rochdale borough, covering 252,857 people. It is an ethnically diverse population, relatively young (23 per cent of people under the age of 18) and experiencing high levels of deprivation.

Model of care

Rochdale place is taking a whole-neighbourhood approach centred around empowering communities, driving prevention, addressing the social determinants of health and reducing inequalities.

Objective

Rochdale has set the outcomes that it expects to deliver for its population through the delivery of six strategic objectives which underpin its vision to ‘create a place that we can all take pride in, where everyone can live a good life now and in the future.’

One of its areas of focus is enhancing its frailty offer to reduce A&E attendances for frailty and the number of adults going into residential and nursing care. The current frailty cohort size is 9,264 and by 2023 this is projected to increase to 15,277, an increase of 61.4 per cent.

Financial flows

The partner organisations have already established pooled budgets between the NHS and local authority using section 75 arrangements and joint posts shared between the ICB, local authority and Northern Care Alliance. They set out ambitious plans in 2018 to develop a whole-population health budget contract held by the LCO by 2023/24. Initial scope included integrated neighbourhood teams, intermediate care, tier 3 weight management, anticoagulation services, and Greater Manchester Devolution transformation funding. Plans to incorporate urgent care spend by 2020/21 were paused due to the pandemic and national financial shifts.

They have, however, continued to develop their level of integration and now operate an ‘all-age, all-in’ approach, aligning governance to support a whole-population health contract. This enables cross-sector collaboration focused on population outcomes, rather than organisational boundaries. For example, they adopted a system-wide strategy for winter resilience funding, collectively identifying key risks and flexibly reallocating resources across partners to address them most effectively.

Next steps

Building on strong foundations, the locality is well positioned to explore new financial models aligned with the NHS 10 Year Health Plan. The locality is keen to explore the opportunity to develop a single contract for the total urgent care budget, supporting delivery of outcomes set out in their locality plan.

Five principles for designing new payment flows

Drawing on our engagement with a small group of ICS leaders, we have identified key principles for developing outcomes-based payment mechanisms. The NHS is currently undergoing a period of intense change, from the merger of NHS England into DHSC and significant operating and corporate cost reductions in ICBs and providers. As strategic commissioners, ICBs will increasingly be focused on developing effective payment models to deliver better value for patients and the public, within a constrained financial environment. This will require the courage to test bold and ambitious approaches and ensure ICBs, and their partners have the right skills and capabilities to deliver on the government’s ambitions.

The vision outlined in the 10 Year Health Plan is the right one. But implementing these new financial flows will challenge long-established principles and ways of working in NHS finance, requiring a shift in mindset across the whole sector, from finance professionals to clinicians. Ultimately, reforming financial flows can help deliver value-based care that improves the lives of patients, staff and clinicians while ensuring taxpayers’ money is used most effectively. Healthcare leaders, with the right tools and support from the centre, are ready to take on this challenge.

Principle 1 - Simplicity is key

To support implementation, new payment mechanisms should be as simple as they can be. A pragmatic and flexible approach from local systems and national teams can ensure financial flows achieve what they set out to do. More complexity increases the risk of unintended consequences.

An outcomes-based approach can become more complex as commissioners and providers may try to attribute causation, even when many outcomes are not solely within control of the health system or individual organisations. Using process or indicator outcomes, using broad and simple measures and building a stronger evidence base can mitigate some of these challenges. Patient and public involvement is key to this as they will be best placed to identify what they need to thrive.

A national shift to better measure, incentivise and oversee improvements in outcomes alongside process, performance and financial indicators for systems is also necessary. Shared outcome frameworks should incorporate outcomes of both clinical and social determinants of health, with methodologies for attribution and measurement that acknowledge system complexity.

Principle 2 - Take a population-based approach

Starting contract development with a target population, rather than a specific clinical pathway, is better for improving population health and helps to address challenges faced by populations with most need who are experiencing fragmented care.

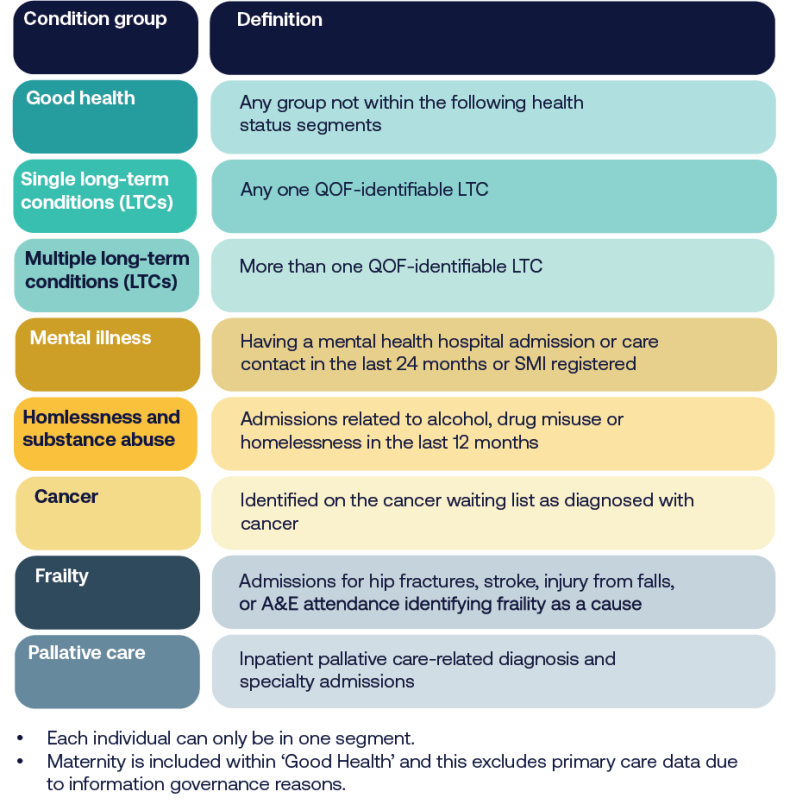

Population segmentation can be a useful way to identify the right population to design new payment approaches for. ICBs are increasingly using linked patient-level data to segment their ICS population into distinct groups to inform service and financial planning. The NHS Confederation’s report on strategic commissioning includes an example from Greater Manchester (see below). To realise a greater impact on population health and managing demand, many ICSs have started with populations with the highest need and who use a higher proportion of public resources.

Principle 3 – Engage stakeholders and bring partners with you

Developing outcomes-based contracting and payment mechanisms approaches requires significant stakeholder engagement and relationship building. It reflects the diplomatic and leadership skills needed to deliver strategic commissioning.

Past experiences of commissioning may lead to scepticism and reluctance from various stakeholders. Strategic commissioning leads need to generate trust, engagement and support within their systems. This is likely to be most effective when starting with a focus on the target population and model of care, understanding where resource shifts are possible then building up to discussing payments and contracting.

A risk-averse NHS culture can be a barrier to implementing new payment approaches. Healthcare leaders should use the vision outlined in the 10 Year Health Plan to support their engagement with partners and the centre. An entrepreneurial gap, with protected innovation spaces and explicit permission to test and fail safely is key to delivering the changed needed.

Principle 4 – Start with the data you have

Data can be a barrier to developing new approaches but starting this work is also an opportunity to gather new data and understand it differently. Members felt that outcomes-based contracting is most likely less widespread because it relies on a deep engagement with local communities and an increased emphasis on capturing and routinely measuring clinical and personal outcomes.

We welcome a strong focus on these issues in the model ICB blueprint. This is an area where ICBs should be growing their capacity and capability. It is an opportunity to develop new skills and set up the right robust data-sharing infrastructure and governance frameworks that enable providers to track outcomes across organisational boundaries while protecting patient privacy.

Data quality and the perception of data quality plays an important role in the trust that organisations put into an outcomes approach. As part of its strategic commissioning offer, the NHS Confederation will be supporting members to develop the right skills and capabilities around population health management and data analysis.

Principle 5 – Align incentives across providers

Key to any new payment approach will be enabling risk sharing across organisations and linking costs and savings across different settings and over longer periods of time.

A balance must be struck between the ‘size of the prize’ being worth it for all partners, particularly larger providers, but also deliverable within a constrained financial environment. The 10 Year Health Plan sets out some initial options for how this could be achieved – through new neighborhood contracts and IHOs – but each system will have to ensure models and structures are adapted to its local context.

Risk sharing should take place between providers, not just between commissioners and providers. Alternatively, contracting forms that bring organisations together, such as alliance contracts, are possible but can create problems where large organisations need multiple contracts to operate at a viable scale. A lead provider may be best placed to align incentives along pathways vertically between providers, as used in the Oxfordshire mental healthcare case study above. In time, this could evolve into a deeper IHO, as proposed in the 10 Year Health Plan. The NHS Confederation will be setting out further proposals for how IHOs could evolve shortly.

Conclusion

Financial flows can be changed to enable the delivery of the three shifts from hospital to community, analogue to digital and sickness to prevention. ICBs and place-based partnerships across the country have already started developing new approaches to link incentives to outcomes and improve population health, not just support episodic care. The examples shared here demonstrate what is possible and share some of the learning so far. Many ICBs are already working to reform payments based around outcomes metrics for population cohorts putting the most pressure on services and costs.

Given widespread deficits across the NHS in England, low patient satisfaction levels and forecast growth in demand for care, reform to financial flows is urgent to help turn the NHS around. 2026-27 will be a crucial year to deliver progress. Yet ongoing cuts to ICBs’ running and programme costs and uncertainty over timelines and redundancies is sapping the capacity to deliver reform. ICB and providers will likely need help from central government to get a first wave of contract reform in place, setting a path for other parts of the country to follow.

Footnotes

- 1. Some examples include mortality age, suicide rate, appropriate and timely response to a person in crisis, percentage of carers offered a carer assessment, percentage of people undertaking a voluntary activity, percentage of people in paid employment, percentage of people undertaking an education programme. ↑