This stocktake highlights insights from medicines optimisation forums on the experience of ICS medicines optimisation so far: the opportunities that exist, the barriers experienced, the support that is needed, and what the vision for medicines optimisation could achieve.

Key points

Delivering on ICSs’ four core purposes. Medicines are the most common healthcare intervention, the most common cause of avoidable harm to patients and the second highest area of NHS spending after staffing. Optimising medicines usage plays a significant role across all four of the ICS priorities: improving population health and healthcare; tackling unequal outcomes and access; enhancing productivity and value for money; and helping the NHS to support broader social and economic development. A strategic role for medicines optimisation in systems – looking across patient pathways from prevention to diagnosis and social prescribing – could unlock significant opportunities to go further and faster in achieving these core aims.

Governance. Since 1 July 2022, statutory ICBs and wider ICSs have been building new governance arrangements to achieve this vision, albeit they are at different stages. Many have recruited directors of medicines optimisation or chief pharmacists and established new medicines boards tying together medicines leadership in different sectors. While building new governance arrangements to adapt to the new statutory structures is crucial to enabling change, it is not an end itself and inevitably this transitional work has consumed time and effort.

Building one team. Building one medicines team – beyond pharmacy teams – requires all parts of the system to work together at a local level, including across the NHS, private providers, social care and the voluntary sector. However, substantial workforce vacancies, exacerbated by competition within systems for the same staff, and a lack of development opportunities to retain, inspire and develop the medicines workforce of tomorrow, are a significant challenge.

Digitising medicines. ICBs are uniquely placed to build a system view of how medicines are prescribed and used and their impact on patient outcomes. There are exciting opportunities for improved digital technology, data sharing and common access to enhance understanding population health, where inequalities in use and access exist, and how to address them.

Progress made, but much more to do. ICSs have made progress with the ‘systemisation’ of medicines optimisation. While this stocktake sets out examples where appropriate governance structures have been created, new pharmacy career pathways developed and new data tools deployed, much of the transformation opportunity still lies ahead. Progress could be accelerated by:

- using system leadership to ‘mainstream’ medicines optimisation in pathway redesign

- ensuring appropriate governance is in place and supports greater focus on transformation

- developing pharmacy workforce plans alongside building awareness of medicines optimisation in wider disciplines

- harnessing digital and data to share medicines records and establish a baseline for improvement

- sharing learning between systems to drive self-improvement.

Medicines in stats

- More than 237 million medication errors are likely made every year in England, costing the NHS approximately £98 million and 1,700 lives each year.

- Up to 10 per cent of hospital admissions in the older population are medicines-related.

- As many as 50 per cent of patients do not take their medicines as intended. Over half of errors (54 per cent) are made at administration and approximately one in five are made during prescribing (21 per cent), with dispensing estimated as accounting for 16 per cent of the total.

Introduction

Medicines are the most common therapeutic intervention and an important enabler for improved care and outcomes, especially with regard to long-term conditions. However, medicines are also the most common cause of avoidable harm to patients and the second highest area of NHS spending after staffing costs. They are associated with a high degree of clinical and financial risk. They also correlate with variation and health inequalities associated with ethnicity and Indices of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) groups.

Following the formation of integrated care systems (ICSs), the NHS Confederation’s ICS Network has convened medicines optimisation forums and conducted a stocktake to better understand how medicines optimisation is developing in a system environment. This work builds on NHS Clinical Commissioner’s reports The Role and Functions of CCG Medicines Optimisation Teams and The Systemisation of Medicines Optimisation, which cover what medicines optimisation is and what medicines optimisation teams currently do.

This stocktake is intended to inform integrated care boards (ICBs), system leaders and NHS England on the experience of ICS medicines optimisation so far – the opportunities that exist, the barriers experienced, what support those working in medicines optimisation need now and ultimately what the vision for medicines optimisation could achieve.

Medicines optimisation plays a significant role across all four of the priorities set for ICSs: improving population health and healthcare; tackling unequal outcomes and access; enhancing productivity and value for money; and helping the NHS to support broader social and economic development. ICB medicines optimisation teams play a vital role in improving population health outcomes and delivering value from NHS resources. They connect the system together as ‘one of the golden threads that run between all sectors of care, whether in prevention or treatment’.

ICSs provide an opportunity for greater integration of health and care services through system partnerships and collaborations. Shifting resources upstream to services, diagnoses and interventions that can better prevent worsening health is a fundamental aspiration of system working. ICSs’ medicines optimisation function can itself be redeveloped to accelerate this change, taking a more strategic role. As ICBs adapt to a reduced running cost allowance, this may present an opportunity to redesign their medicines optimisation function so it is better connected with other teams and geared to deliver transformation. This stocktake report suggests four immediate priority areas of focus for ICBs to achieve this shift in medicines optimisation:

- Setting the vision for the broader strategic role of medicines optimisation.

- Putting the right governance in place so decisions can be made at the right level, at the right time in the right way.

- Building ‘one medicine team’ across all parts of the system.

- Improving digital interoperability and use of data to drive population health improvement.

Methodology

This stocktake is based on the experiences of a range of stakeholders involved in medicines optimisation both within ICBs and in other parts of the health and care system. The ICS Network convened three medicines optimisation forums around the topics of governance, workforce, and digital and data that brought together senior leaders from across systems. This was supplemented by a series of interviews conducted in early 2023 to gather a detailed and diverse range of experiences. Engagement included ICB pharmacists, ICB chairs, provider chief pharmacists, heads of medicine optimisation and representatives at NHS England, NICE and PrescQIPP, and included provider, voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) and arm’s-length bodies (ALBs).

Medicines optimisation plays a critical role in every one of the four core purposes set out for ICSs

Improve population health and healthcare

- Ensure patient safety and improved quality of care with integrated medication reviews across primary and secondary care prescriptions to ‘First Do No Harm.’

- Develop shared care protocols and triangulate data to assess compliance and health outcomes.

- Use innovative diagnostics, drugs, devices and digital technologies to improve health outcomes.

Tackle unequal outcomes and access

- Identify the CORE20PLUS5 priorities and opportunities to improve access to medicines and social prescribing.

- Identify medicines use and social prescribing best practice for each of the CORE20PLUS5 priorities.

Enhance productivity and value for money

- Implement NICE guidelines and best practice on clinical effectiveness.

- Shift the mindset from cost saving and budget management to investment, value for money and the return on investment of improved patient outcomes from medicinal interventions and medical devices over a whole care pathway.

- Drive investment in primary care medicines to avoid more expensive secondary care interventions.

- Decommission medicines and prescribing when no longer appropriate to meet local population health needs.

Help the NHS to support broader social and economic development

- Enable people with long-term and multiple health conditions to continue to work and live independently for as long as possible.

- Improve quality of life and reduce demand for NHS services through appropriate use of social prescribing.

- Reduce the use of dependence-forming medicines.

- Leverage the NHS’s capability to undertake research, monitor outcomes and uptake innovative medicines.

Current context

ICSs are still very early in their development and in a difficult position of being required to deliver the care of today, recover from the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, and transform into systems fit for the future. Leaders consistently describe a situation of not having the ‘head space’ to achieve truly transformative approaches to care, with limited time and a vast number of competing priorities. The King’s Fund described ICSs as having been ‘born into a storm’ and while this might be a force for change for some, it is important to understand this is a very challenging context for all.

Building collaborative ways of working takes time and sustained effort and focus. The NHS Confederation has previously suggested that it may take around three to five years before systems achieve intended benefits for population health, clinical quality and value.

While creating opportunities to better integrate care pathways, the recent delegation of primary pharmacy, ophthalmology and dentistry (POD) commissioning to all ICBs, as of 1 April 2023, adds further pressure on ICSs’ capacity. The NHS Confederation has published a complementary report reflecting on the experiences of nine ICBs who took on delegation community pharmacy commissioning early from 1 July 2022.

The current landscape is complicated by the forthcoming expiration of the present voluntary scheme for branded medicines, pricing, and access (VPAS). The scheme was negotiated with major pharmaceutical manufacturers to promote uptake of innovative medicines within the NHS while ensuring the costs of those innovative drugs would not rise unsustainably. The scheme set out an affordability mechanism under which pharmaceutical manufacturers pay a percentage of their net sales of branded medicines back to the system as a rebate. Negotiations for the next VPAS agreement are currently underway and a mutual agreement will be essential for the continuing uptake of innovative medicines across the NHS.

The five-year arrangement (finishing in December 2023) has an agreed growth rate cap of 2 per cent annually for branded drugs, excluding levies for the most innovative drugs. In 2021 there was exceptional growth in the sale of branded medicines (in part from COVID-19) with the total sales growth jumping to over 9 per cent, which was significantly in excess of the allowed growth rate of 2 per cent. The 2023 repayment percentage was calculated at 26.5 per cent sales, causing great concern with participating companies. Predicted returns of sales revenue from participants to the NHS for branded medicines is anticipated to be approximately £3.3 billion, which is a substantial increase from £0.6 billion in 2021 and £1.8 billion in 2022. Predicted returns of sales revenue from participants to the NHS for branded medicines is approximately £3.3 billion, from £0.6 billion in 2021 and £1.8 billion in 2022.

In spite of these challenges, the pharmacy workforce has great potential to further contribute to the future sustainability of the NHS

The scale of the challenge should not be underestimated as medicines optimisation teams deliver their core functions, take on additional responsibilities through delegated commissioning and look to transform the way they work across their new systems. With workforce shortages and a challenging environment, this additional responsibility and workload is happening without any additional funding or capacity. In spite of these challenges, the pharmacy workforce has great potential to further contribute to the future sustainability of the NHS, as described in the Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s recently published A Vision for Pharmacy Professional Practice in England.

ICS medicine optimisation teams are at the beginning of this journey and understandably there is variation in progress. We have heard that some areas are starting to implement a system prescribing approach and for others it feels that very little has yet changed.

Barriers to system working

ICB medicines optimisation teams and providers both need time to identify who is who with their local system and build new relationships across different teams. There is often not sufficient capacity in systems to drive medicines optimisation transformation at the same time as doing the operational work. The planned reduction to ICBs’ running cost allowance and organisational change will add to this complexity and could make this challenging, slowing the pace of change.

...the transformative potential of medicines optimisation is not routinely invested in

Even though medicines optimisation cuts across all aspects of care in all settings, it is sometimes not well understood and is often seen as separate, technical and transactional. This perception has made it difficult for some teams to engage in the right discussions within their system at the appropriate time, when services are being redesigned. Teams are often brought into these at a late stage and while there are areas where progress has been made, the transformative potential of medicines optimisation is not routinely invested in.

A focus on systems is also highlighting some very practical barriers to working together in a more integrated way. We have heard examples of how patient safety and experience could be improved, resource could be freed up and significant efficiencies made, but there are barriers to system working that need to be addressed. For example, there is often a lack of interoperability between IT systems, particularly important in the context of linking patient records to share data effectively.

Incentives can be misaligned across different providers within a system, sometimes making it impossible to collaborate and transform services in a way that better serves patients and provides the best value. In new systems where collaboration is the priority, it is important to identify where these barriers are and how they can be overcome.

While the Health and Care Act 2022 created the legal structures to enable integrated working, further changes to culture and behaviour are needed to enable ICSs to succeed, including in ICSs’ aspirations for medicines optimisation. The Hewitt review sets out recommendations to support ICSs to better achieve their four core purposes, in particular to incentivise and automate the flow and quality of data between providers and systems; longer-term financial planning with greater local autonomy over budget allocations; and the development of self-improving systems. If implemented, these could provide a firmer basis for the change medicines optimisation teams want to deliver

Addressing misaligned incentives

ICSs have the potential to transform the way medicines are delivered, by taking a system view to improve safety and find efficiencies. We have heard there are opportunities for NHS trusts to devolve some of their dispensing to community pharmacies, including complex medicines, utilising anticipated extension of the national electronic prescription service to secondary care. This could improve access for patients as their medicines would be dispensed closer to home, be better for community pharmacy as it would allow them to use more clinical skills, and be better for the hospital as it releases their capacity.

One reason this is currently not possible is that community pharmacy does not have access to the same discounts on drugs that NHS trusts do. If trusts devolved this dispensing to community pharmacies the trust would have to pay the full list price for drugs that it currently gets a discount on, which is unaffordable. While this is less of an issue for generics, it is a challenge for high-tech medicines such as oral chemotherapy or immunotherapy drugs and monoclonal antibody therapies. These high-tech or specialised medicines are a small minority of the medicines prescribed by a hospital but account for the majority of hospital medicines costs, while most more conventional medicines account for a smaller proportion of the cost. A three-way agreement between hospital, community pharmacy and the pharma company could enable improved system working by eliminating these inefficient allocations of prescribing responsibilities and resource.

The vision for medicines optimisation

Medicines, the most common medical intervention in the NHS, continue to be seen as a cost rather than recognised for their wider value. A values-based approach would treat medicines as a creator of health and be valued by the long-term impact of a medicine on a patient’s health and quality of life, as well as consequences avoided and interventions averted through their use. Such a view recognises medicines’ overall return on investment rather than simply a cost.

We have consistently heard there could be significant opportunities for medicines optimisation to improve population health, reduce unequal outcomes and access, and support a more values-based approach to care. The cost-of-living crisis, for example, is undoubtedly having an impact on whether patients are collecting their prescriptions. Identifying these at-risk people early on will be critical to reducing health inequalities, unequal access and outcomes and preventing further ill health and more complex interventions.

Tackling unequal outcomes and access: using CORE20PLUS5 to drive decisions

Frimley ICS is using the national ambition CORE20PLUS5 to inform action and reduce health inequalities. For example, they have assessed the impact of inequitable management of diabetes on their population and the system.

Frimley targeted a particular cohort of 30,000 patients within diabetes care and, using the population insight team, has been able to understand the patients’ healthcare utilisation. This includes how many times the patients go to the GP, how many medicines they are taking, and how many hospital admissions have they had prevalence of clinical markers such as haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), which measures the amount of blood sugar (glucose) attached to haemoglobin.

It is then possible to make decisions about which interventions to invest in to better meet health needs and understand the impact on outcomes and healthcare utilisation and prevention. For example, do we need better diagnosis? Education? Medicines optimisation? In response, Frimley has focused on early diagnosis, targeted and structured medication reviews and the use of wearable technology. This has helped to better understand the impact on primary and secondary care.

Population health insight has allowed Frimley ICS to take a patient-centred approach. There is a dedicated population insights team that has designed a platform that pulls data from several different sources, including primary and secondary care data.

Enablers for collaboration and system working

Building relationships and trust takes time. The role of leadership in championing collaboration and ‘winning hearts and minds’ was consistently said to be fundamental to people working more collaboratively across a system. Having a shared vison and aligning priorities against a common set of goals enabled progress to be made. Those systems further down the line suggest this takes in excess of a year. This is true, not just in medicines optimisation, but across system working.

Separate organisations often focus on individual medicines budgets and the reduction of costs, rather than taking a system view as they have been incentivised to do until recently. Whereas planning care with a focus on the patient pathway, where a values-based approach is paramount and can support a more collaborative approach to medicines value and optimisation. Creating the opportunity for such system oversight of pathways of care, where people still have accountability for their part, allows visibility of the benefit of interventions to the whole system.

A value approach to medicines prescribing sees the health created by a medicine or device as a long-term benefit, in contrast to the traditional view of medicines as a cost to be borne

A value approach to medicines prescribing sees the health created by a medicine or device as a long-term benefit, in contrast to the traditional view of medicines as a cost to be borne. Timely prescription of medicines before conditions exacerbate can lead to healthier patients while requiring fewer specialised interventions. For example, earlier prescription of medicines to patients with rheumatoid arthritis can lead to fewer joint replacements carried out later with associated better outcomes for the patient and fewer costly surgical interventions. A system view is essential for redesigning patient pathways to allow such opportunities, as well as capturing the resulting benefits to the patient and the public purse.

We also heard that the profile of medicines optimisation teams and pharmacists needs to be raised and those working across the system understand the value they can bring, ensuring the medicines and pharmacy voice has a seat at the table alongside medical and nursing colleagues when re-designing pathways of care. Too often they are brought to discussions too late and their essential contribution not included at the right time.

Delivering transformation and bringing all parts of the system together can be an overwhelming task. For example, some of the innovative approaches to linking patient records are highly complex. Some of our interviewees recommended identifying a starting point. Starting small can have its advantages and building transformative programmes over time can be more effective.

Involving people with programme management skills and experience of transformation can also be a key enabler. We heard this skill set makes a real difference to initiating and sustaining change. One system we spoke to has established a transformation board for the ICS so that teams can draw on this expertise to support their development needs.

Unlocking the transformative

A better understanding of medicines optimisation is still needed. It should be seen as a function that can help drive value across a system, rather than the responsibility of one team in isolation. To unlock the potential of medicines optimisation, existing perceptions need to be challenged so there can be a focus on its value.

As the NHS Confederation has previously said:

“The delivery of value and quality, improving patient outcomes and reducing health inequalities is at the heart of medicines optimisation. A committed workforce of GPs, pharmacists, pharmacy technicians and other professionals are dedicated to achieving this. While medicines optimisation is about so much more than just delivering cost savings for the NHS, it is an inescapable fact that an ever-increasing proportion of overall NHS expenditure is consumed by medicines and the level of risk of avoidable harm associated with medicines overuse is significant. Optimising medicines improves quality and outcomes, as well as providing greater value for money.”

Transforming medicines optimisation to include its broader and more strategic role could unlock significant opportunities. System-wide effort and co-operation is needed to deliver on these opportunities and the impact of this work needs also to be measured across the system and at a strategic level. Deprescribing and stopping harms caused by inappropriate polypharmacy and putting appropriate prevention measures in place is a system-wide undertaking and its impact will be broad, requiring careful assessment. Similarly, patient pathways can be strategically designed from prevention to diagnosis and treatment, with use of medicines, specialist medicines and social prescribing delivering healthier populations with fewer medical interventions.

Patients not completing their prescribed treatments or not taking medication as prescribed is a known problem, affecting a multiplicity of clinical outcomes and populations

This could enable a values-based approach centred on empowering patients to make informed decisions about their own healthcare. In such a model, greater investment might be put into prevention, social prescribing and primary care medicines affording the patient more personalised care options. Preventing more complex interventions, or interventions that patients might not want, may mean that the cost of medicines in primary care might need to increase providing greater value for patients and the system across the whole patient pathway. Moving from siloed to broader analysis requires the appropriate data and collaboration within the system and actively redesigning patient pathways. Patients not completing their prescribed treatments or not taking medication as prescribed is a known problem, affecting a multiplicity of clinical outcomes and populations. A greater focus on the therapeutic relationship between the service user and the entirety of the clinical team could help improve this issue and support a move to a values-centred approach.

Achieving this shift also will require NHS staff to work with patients to better understand their lifestyles and what they want to achieve from their care. Increasing the use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) could help to build this picture. It could also contribute to broader social and economic development by enabling people with long-term and multiple health conditions to continue to work and live independently for as long as possible. 2.5 million people are currently not in work due to long-term sickness and research commissioned by the NHS Confederation suggests that ‘for every pound of public money invested in the NHS, £4 is recouped through gains in productivity and increased participation in the labour market.’

Some members are already working towards a system prescribing approach to align different parts of the system against shared outcomes and enable a much broader view of the value and impact of medicines. This includes aligning budgets, or even having shared budgets, which requires finance teams, pharmacy teams, providers and ICBs to work together and necessitates a huge amount of trust and significant changes to existing ways of working.

Developing governance arrangements

ICB understanding, oversight and assurances of medicines optimisation is critically important given the patient impact of medicines, including the risks associated with inappropriate polypharmacy, medication misuse and prescribing errors. The NHS Long Term Plan set out objectives to reduce the misuse of medicines, improve medicines uptake, promote self-care and reduce waste for the 50 per cent of patients who do not take their medicines as intended.

Different systems report different approaches to medicines optimisation governance, often dependent on the size of system. ICSs are also at very different stages of developing their governance. For example, some will have an appointed chief pharmacist at ICB level and others will instead have a senior representative, depending on the size of the system and ability to fund additional posts. Some are establishing new medicines boards for the first time that report to the ICB. Publishing these structures would help share approaches and learning across ICSs.

Identifying very senior leadership

We heard very positive feedback about the role of the chief pharmacist in an ICB, with one person having the oversight and accountability for medicines optimisation at a very senior level and the opportunity to co-ordinate better medicines usage. Senior leadership at board level has enabled some areas to progress more quickly. Although this role does not necessarily need to be an ICB chief pharmacist, a dedicated, fully funded role ensures there is consistent leadership for better medicines usage at ICB level. This very senior leadership has the authority to provide a strong voice at ICB level and pull medicines teams together at a local level. Senior leaders will need time and capacity to be able to lead the transformation of services.

Strengthening ICB oversight and understanding of medicines

Medicines optimisation teams across ICBs and providers could be enabled to achieve ICSs’ four core purposes, by greater understanding of their role by colleagues. Medicines are a facilitator for most programmes and asking ‘what is the place of medicines in this?’ is an important first step.

Decisions are made differently across different parts of the system, involving a range of professionals and disciplines. Bringing practice together under guiding principles of good medicines governance is challenging but possible, focusing on overall prescribing, what shared care agreements look like and where the budgets sit.

Many systems have set up an overarching medicines optimisation board or integrated medicines optimisation committee (IMOC) for the first time, to oversee medicines at a system level. Getting these committees in place has proven to be key in terms of having appropriate oversight and governance in place to make decisions. With final decisions made at a system level, this can also help drive a more systems-focused way of thinking.

Interviewees highlighted potential tensions between what functions are undertaken at place level, by systems, and by provider collaboratives. ICBs should engage colleagues from across their systems to consider how they facilitate medicines optimisation at a local level and maintain the appropriate levels of assurances and oversight. Systems will implement their own solutions with a diversity of approaches; capturing and sharing best practice and learning can help accelerate improvement.

Aside from the governance for existing medicines, ICBs will also need to consider how they will develop the appropriate expertise and manage the oversight of new medicines coming down the pipeline. This will be particularly important as ICBs prepare to take on commissioning of those specialised services identified as suitable and ready for greater ICS leadership under joint commissioning arrangements from April 2023 and planned delegation from 2024. As medicines and genomics become increasingly intertwined, ICBs will need to consider how they feed into NICE consultations and make decisions about new medicines.

Appropriate oversight and assurances – the case of sodium valproate

Sodium valproate is a drug used to treat epilepsy and bipolar disorder. While it can produce health benefits, if taken when pregnant it poses substantial risks, potentially causing birth defects, and problems with learning and development. While this is known, sodium valproate continues to be prescribed to pregnant people in some contexts. There are ongoing reminders to healthcare professionals of the risks associated with exposure to valproate in pregnancy.

The Valproate Pregnancy Prevention Programme was published by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) in September 2018, yet it is still in some cases being prescribed in pregnancy. The Commission on Human Medicines (CHM) has advised that there should be greater scrutiny of the way valproate is prescribed and that further risk minimisation measures are required.

ICSs need to support prescribers to be reminded of the risks and to develop methods of peer scrutiny that help minimise exposure in pregnancy.

ICBs should have the oversight and assurances in place to make the use of valproate (in all its forms and all its uses) as safe as possible, striving to eliminate congenital harm while providing the best possible care for patients, preventing deaths from their conditions.

Managing risk

Further work is required to better understand how risk within an ICS is categorised and mitigated and how the risks associated with medicines are managed across a system, including both clinical and financial risk. This will be complex and getting the right assurances in place and the right level of oversight will be critical in terms of patient safety, requiring the specialist expertise of medicines optimisation teams to help unpick this. We heard this should be balanced against a ‘tolerance of uncertainty’ so that teams are not overwhelmed by bureaucracy.

Managing risk will be especially important for the entry of medical technologies into the system, where there is need for greater leadership and governance. Understanding the role of pharmacy professionals in the monitoring of medical technologies and understanding of the affordability and value will be important.

Improving visibility across systems

Greater clarity and visibility of colleagues’ roles and expertise would be beneficial. We heard there are challenges around the visibility and coordination of the functions of ICSs and across medicines teams. For example, who are the experts in different areas and what information do they have access to? There are many functions in an ICS, with numerous groups and meetings needed to deliver any given project. Transformation often sits across numerous professionals and requires a great degree of team working, often with different people doing different bits of transformation.

Relying on professional relationships is insufficient to deliver transformation and effort needs to be put into facilitating improved mutual understanding. Responsibilities are often clear within an individual medicines team but not as clear outside of it, especially in primary care. As an initial step, efforts should be made to ensure relevant pharmacy professionals including community pharmacists are able to connect at a place or system level as appropriate, to know who each other are, what they are responsible for and understand their respective roles.

Identifying synergies and pooling effort

Some of our interviewees could see synergies that might exist across different ICBs and were keen to explore these where possible, for example in tertiary care prescribing. ICBs exist on a spectrum of scale, with different resources. While many areas of work will need specialised approaches and local plans there are substantial areas of work that would have similar solutions. Cooperation between ICBs on similar projects would support this, as would an ongoing dialogue with NHS England and medicines optimisation leaders to identify these common challenges and provide and support solutions. Some ICBs are developing ‘lead ICB’ models in their local area and it would be helpful to explore how this type of model could support the transformation of medicines optimisation.

Case study: Frimley Park - ratifying decisions under a single integrated medicines optimisation board

Prior to the creation of statutory integrated care systems, most decisions on primary and secondary care were made through separate committees and structures. The ICS set up a medicines board including partners from across the system, reporting to the ICB, and with primary care medicines and secondary care sub-committees. These sub-committees agreed new principles for good medicines governance and a shared focus on overall prescribing and shared care agreements, which they oversee delivery of.

The medicine board has helped colleagues to consider the broader opportunities for their populations with one ultimate budget. Frimley’s medicine board is made up of a diverse array of pharmacy colleagues and executives from across different disciplines, including chief nursing officer, chief medical officer, prescribing leads, clinical directors, finance and quality alongside colleagues from providers. The multi-disciplinary nature of the board, importantly broadening beyond just pharmacy, widened the perspective to improve decision-making by looking at wider system implications.

Building one medicines team

The current workforce environment is extremely challenging, with significant numbers of vacancies, staff shortages and a lack of development opportunities to retain, develop and inspire the workforce of tomorrow. For example, we heard there is significant competition between primary care providers and NHS trusts over the same pharmacy professionals. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society sets out a convincing vision of professional pharmacy practice in ten years, which clearly articulates the growing roles and responsibilities of pharmacy teams. ICB leadership of a system-wide approach to workforce planning, from university education through to career development and training, can help to manage such competition while addressing long-term supply issues.

Building one medicines team requires all parts of the system and those working at a local level, including across the acute sector, primary care networks (PCNs), private providers, social care and the voluntary sector.

Building relationships and trust

Interviewees consistently discussed the importance of building relationships and trust across the system, recognising this takes time and capacity. This is a common theme across all system working and applies equally in the case of medicines optimisation. Leaders describe their ambition to improve collaboration across all providers at a local level and reduce siloed working and this has been borne out in some places where this is starting to be the case, even becoming the norm.

Building collaborative networks takes time but is progressing well in many areas. Teams are now often working with other teams that they would not previously have worked with, whether within ICBs or across the wider ICSs transformation is happening, albeit at different rates.

Developing the right workforce and capabilities

ICBs are starting to consider new and innovative roles for pharmacy professionals to help retain and inspire people to join the profession. This includes the ambition to create rotational roles that would allow pharmacy professionals to work in different parts of the system, as well allowing cross-sector appointments. This could not only make roles more attractive and encourage career progression, but also improve knowledge and understanding of the system itself encouraging better working practices and refinement of processes throughout a system. Some leaders shared their ambition to start discussing opportunities with universities and working with students to develop the roles and opportunities of the future. This is still in its infancy but there is enthusiasm to progress quickly and continues a well-established trend of building the expertise of the pharmacy profession, leveraging qualifications to drive up quality while building attractive care.

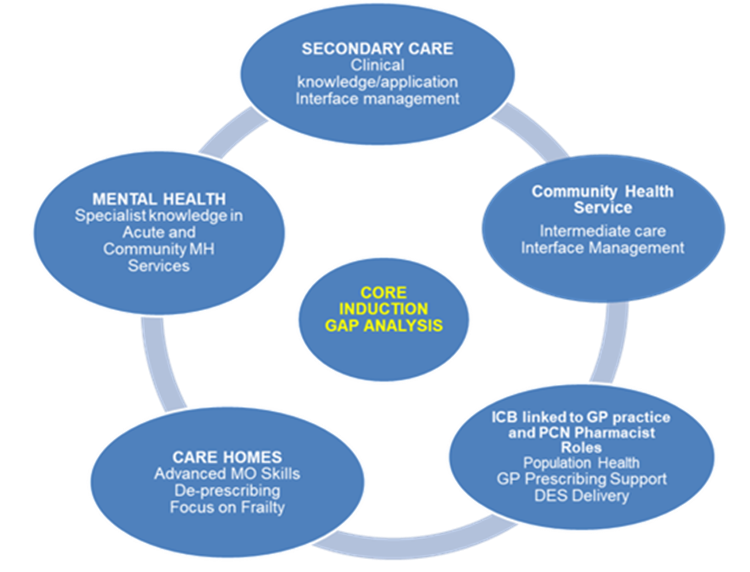

Investment in education and training to support existing pharmacy professionals, while building the capacity and capability to deliver the more complex and demanding strategic medicines optimisation functions, will be essential to systems in the future. Ideally, pharmacy professionals training would be tailored to the system they are going to be operating in. In particular, we heard an example of rotational training schemes between acute, the community, care homes, mental health and primary care that would be good to share more widely, including how these are managed and funded.

Some interviewees discussed the potential role of consultant pharmacists as clinical leaders in a system; these roles predominantly sit within secondary care providers at present. With their combined responsibilities for research, teaching and clinical practice, there could be opportunities for them to lead more transformational approaches, particularly in relation to patient pathways as they will often have a particular specialism. Training in change management could help the workforce to accelerate this transformation.

While this emerging picture of a more system-based workforce is where some ICBs are trying to get to, there are barriers to be considered. It can be challenging to initiate consultant pharmacists and build the business case for them. In relation to rotational and cross-sector roles, we heard there will be challenges around some organisations offering NHS terms of service, including pensions, and GP practices and community pharmacy not being able to. There would need to be clarity on which organisation sits with the risk, who is responsible for the training and how you distribute them fairly across the system. As these innovative roles develop it would be beneficial to share how they have been structured.

Case study: Rotational education and training in East Sussex, the Multi-sector Foundation to Advanced Training programme

The Interim NHS People Plan (2019) emphasised the importance of cross-sector training to meet the workforce needed for integrated care systems, as part of the NHS Long Term Plan. Health Education England (HEE) Kent, Surrey and Sussex funded the East Sussex Multi-sector Foundation to Advanced Vocational Training Scheme (VTS) for pharmacy professionals, a multi-sector pilot programme developed in collaboration with local partners.

The scheme supports qualified pharmacists with at least two years’ registration to broaden their scope of practice to a multi-sector role. It aims to develop a system-wide flexible workforce and deliver more integrated medicines optimisation.

Trainees spend two years across the following areas:

- Induction hosted by secondary care (East Sussex Healthcare NHS Trust)

- Three months in secondary care services.

- Four months in Medicines Optimisation in Care Homes (MOCH) team.

- Three months in mental health services.

- Three months in community health services.

- Four months in the ICB (was CCG) medicines optimisation team.

- Six months in primary care networks.

The training programme has resulted in a number of benefits:

- An opportunity to harness local talent.

- Improved career opportunities.

- Improved trainees’ system-level understanding.

- Development of flexible, adaptable and transferrable skills focused on the individual patient’s needs.

- Improved service and retention, with an overall retention rate in the local ICS in excess of 70 per cent.

The team highlighted the following lessons learned so far:

- Programme resource and a lead organisation willing to host the trainees are key to making programme work.

- Having pharmacists working across sectors encouraged more joint working and sharing of information between care providers which will have a positive impact on patient care.

- IT governance can be an issue and MOUs across systems are important to remove any barriers to appropriate sharing of information.

- Some dedicated support and supervision of trainees is required from within their different placements.

- HR advice on employment contracts is essential as is clarity on the governance and oversight of the programme.

What the trainees say

“I am a different pharmacist following my VTS year, I have gained so much more expertise and confidence in performing my role and have strengthened my clinical skills far beyond my initial expectations.”

“The VTS has given me the opportunity to develop collaboration with the MDT and review patients holistically.”

Strengthening the voice of all parts of the one medicines team

As ICSs continue to develop, bringing together voices from all parts of the system will be integral to their success. With their new delegated responsibilities for commissioning pharmacy services, systems have an opportunity to strengthen the local voice of community pharmacy, ensure it is strategically aligned, invested in and is sustainable. The NHS Confederation has learned that local levels of engagement with pharmacy, optometry and dental (POD) providers varies across systems and while some areas have engaged regularly with pharmacy professionals, ‘in other systems these providers struggle for a voice.’ There are lessons from the nine early adopter systems and the NHS Confederation has recently published a report outlining their experiences and a series of recommendations. Delegation of community pharmacy commissioning to all ICBs from 1 April 2023 enables them to commission across whole pathways and better integrate care and services.

Use of data and digital technology

The challenges around sharing data, digital interoperability and unfit IT systems are not unique to medicines optimisation. This is a long-standing challenge for organisations that will be increasingly exposed as ICSs develop and increase collaboration across different parts of a system. These challenges could serve as significant barriers to progress.

There is a very varied picture for medicines optimisation, from time-consuming manual workarounds to innovative approaches to using digital technology and linking data and records. Overcoming these challenges requires prioritisation as well as financial and workforce capacity and capability, currently under enormous strain.

The opportunities for improved digital technology, data sharing and linking of data sources is exciting. If ICBs are able to build a system view of prescribing, how medicines are used and their impact on patient outcomes, this could contribute significantly to understanding population health and other clinical programmes, including where inequalities exist in terms of use and access.

The Hewitt review makes welcome proposals to incentivise and automate the flow and quality of data between providers and systems, alongside development of a minimum data-sharing standards framework and building in-house teams to train frontline staff to adapt to new digital tools.

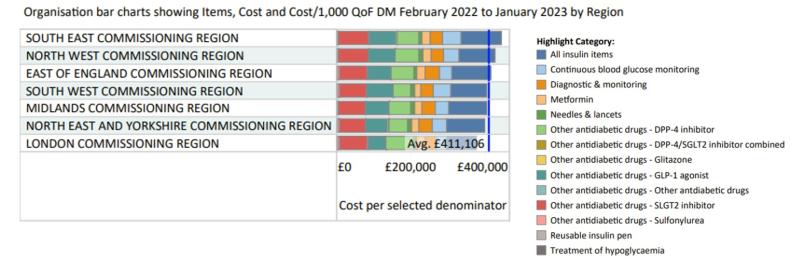

PrescQIPP clinical prescribing snapshots

PRESCQIPP IS A not-for-profit community interest company that supports NHS organisations with prescribing data and supports medicines optimisation through producing a range of bulletins, data sets and training across a range of clinical subjects.

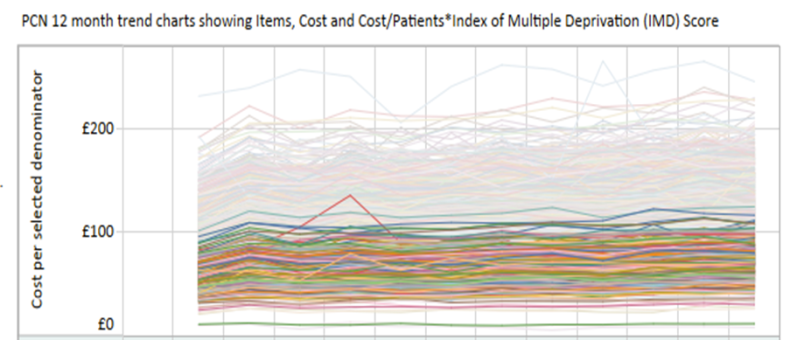

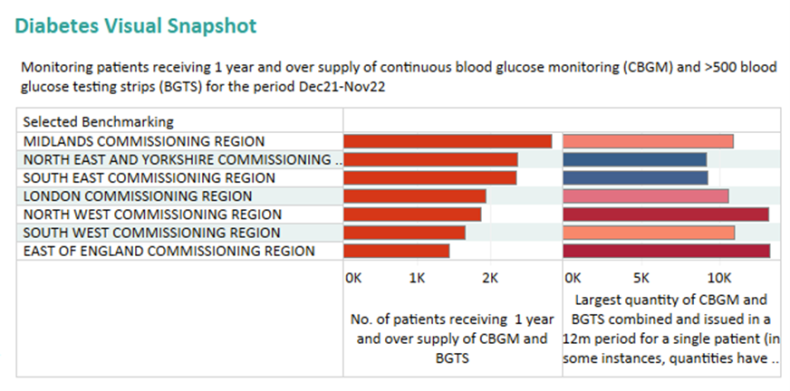

PrescQIPP’s clinical snapshots provide an overview of prescribing data in individual clinical areas and contain a range of visualisations to support reviewing prescribing for that area. These incorporate the Indices of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) data to highlight any differences in prescribing for more deprived areas, Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) prevalence data and also the pseudo-anonymised patient-level prescribing data, which can be used to highlight any overprescribing issues.

The diabetes clinical snapshot breaks down prescribing spend in different groupings of antidiabetic drugs and devices to show how medicines are being used locally across the pathway. Several denominators allow spend comparisons across different areas. The chart below shows spend per 1,000 QOF-registered diabetes patients broken down by drug and device category.

Trends over time and spend per denominator can be explored in the clinical snapshots. The chart below shows spend per population based on IMD deprivation score at PCN level in England for prescribing of all antidiabetic drugs and monitoring devices. The top 20 per cent most deprived PCNs have been highlighted and as can be seen the spend per denominator is all at the lower end.

The pseudo-anonymised patient-level data views indicate where overprescribing may be an issue. The chart below shows the number of patients per region who have been supplied with a one-year supply of continuous glucose monitoring sensors, as well as 500 or more blood glucose testing strips on the left hand side and the maximum quantities prescribed for individual patients on the right.

Visit the PrescQIPP clinical snapshots page to explore this data further.

Digital technology and linking records

Digital technology continues to be an enabler for data sharing and access to data, including access to and editing of patient records, medicines history and discharge information. Pharmacy professionals and all prescribers having access to and being able to edit primary care records of each patient could enable different parts of the system to work together. Progress is being made against the NHS Long Term Plan target for all providers to implement electronic prescribing, aiming to reduce errors by up to 30 per cent.

This is a complex and challenging area that can take years to achieve, requiring leadership, workforce capacity and investment. While progress is being made it continues to be a barrier to transforming medicines optimisation across a system. Where ICSs have progressed this, it would be helpful to share their experiences.

Use of data to drive improvement

Having oversight of medicines prescribing can empower ICSs to better understand the impact at a system level. What is less clear, we have learned, is what this data could include and how to build a more in-depth picture of how medicines are impacting population health. Taking a system view of medicines optimisation highlights where there are opportunities to use multiple data sets together to build a more complete picture of medicines usage, it also highlights where there are gaps. Researchers have recently highlighted that there are no UK medication error data available for some stages of the medication process and none for any stage of the process in care homes.

A community pharmacy blood pressure check service is now live on the SHAPE Atlas, allowing ICBs to use data along with the delegated commissioning capabilities to target specific communities for cardiovascular disease prevention.

For example, to build an accurate picture of the use and impact of medicines, ICSs should move beyond looking at prescribing data, as this in isolation does not evidence how and whether medicines are being used and the impact they are having at patient level. Linking to dispensing data and patient outcome data will build a more complete picture and enable systems to see where interventions may need to be put in place. It would be helpful to understand where there are potential gaps in the data and how this can be improved. This is especially important for the inequalities agenda, for example to build a more complete picture of how people are accessing and using medicines. (See graphs below).

Medicines optimisation teams hold a vast amount of prescribing data that can be cumbersome to manipulate and challenging to share across the system. Better data sharing can support the population health agenda and could help predict future medicines usage and enhance our understanding of future health and care needs in system populations. ICSs provide an opportunity to take this system view through the use of data. It would be helpful to do further work to understand how best to build a more accurate picture through data and learn from areas starting to do this.

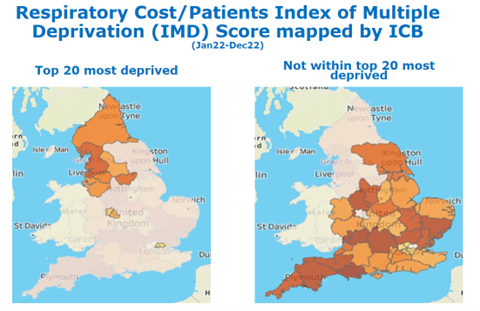

The graphs below show respiratory costs by ICS using the Index of Multiple Deprivation (calculated using the total cost for all respiratory medicines prescribed in the last 12 months divided by the IMD score). The darker the red the higher the cost, suggesting people in the most deprived areas may not be accessing the treatment they may need.

Case study: Establishing a unified medicines record, Lancashire and South Cumbria

Lancashire and South Cumbria ICS is aiming to consolidate all medicines sources locally into one unified medicines record to ensure that a clinician can see what a patient is taking at the point of need, including GP, hospital outpatient, community drugs teams, mental health clinics, homecare and chemotherapy. The record will be interoperable to remove the need for transcription, making a big difference to hospital prescribers and reducing the impact of transcribing errors.

The team has also considered the opportunities for secondary uses of data, identifying the following opportunities:

- A critical medicines alert on hospital admission so that clinical staff can make sure patients don't miss any doses of critical medicines, such as anti-Parkinson's medication or anti-epilepsy medication.

- Factoring in anticholinergic burden scores so when a review is taking place they can be factored in (anticholinergic medications can increase the morbidity of a patient at home and increase their likelihood of being admitted to hospital).

This approach will also include referrals – the ICS’s ReferToPharmacy system allows hospital pharmacy to refer to community pharmacy for the discharge medicines service. This is being expandded to the whole ICS and in time will include community drugs teams and care home teams. It allows staff to know when a person they care for is admitted to hospital, when they are discharged and whether their medicines have changed.

There have been challenges around completeness of data and bringing all of the sources together, with five different acute trusts in the ICS. Also challenges with data quality but this should improve over time. A good user experience will be very important to its success.

The programme of work requires significant financial investment and will need further investment to ensure sustainability.

Enablers:

- This has all been made possible through the use of standards. For example, prescribing in a hospital differs from prescribing in the community, the application of standards allows different systems to present the same information in a slightly different way that is contextually correct for them.

- The Information Standards Notice (ISN) requiring suppliers of electronic prescribing software to be interoperable with others, has been critical.

- Selling the vision and the significant benefits to the ICB and making it a priority workstream.

- Starting with a small team and finding the funding (£705,000), building from there over time.

Conclusion

Medicines optimisation offers significant opportunities for ICBs to achieve their four core purposes. Understanding the broader strategic role of medicines optimisation has the potential to provide significant value to ICSs and ensure that they are better able to improve the health of the population that they serve. Medicines are everyone’s business and bringing pharmacy professionals to the table as part of a multi-disciplinary team to design services across a system should be the norm.

ICSs have made progress with the ‘systemisation’ of medicines optimisation, starting with agreeing shared priorities across each system. This stocktake has set out examples of where appropriate governance structures have been created, new pharmacy career pathways developed and new data tools deployed. There is understandable variation in terms of how medicines optimisation is transforming at a system level, with ICSs facing different challenges depending on their size, make-up and complexity. Indeed, given limited capacity and different populations needs, such warranted variation is part of ICS design, giving systems freedom to take different approaches. That this stocktake considers many of the outstanding opportunities, however, is a reflection of the fact that much of the potential transformation still lies ahead. At the time of publication, little over nine months since the Health and Care Act 2022 came into effect, adjusting governance arrangements to the new statutory structures, including the appointment of ICB chief pharmacists, while continuing day-to-day operations, has consumed much of ICBs’ energy.

Going further and faster with medicines optimisation transformation can be enabled by learning from the experiences of systems that are further ahead. This is particularly important as ICBs take on increasing commissioning responsibilities. The NHS Confederation will aim to support such learning over the year ahead.

Recommendations

To build on progress made to date and go further in harnessing medicines optimisation to deliver on ICSs’ four core purposes, this stocktake makes the following suggestions for ICSs to consider, based on the reflections from their peers:

- System leadership

ICS leaders, including but not limited to chief pharmacists, should ensure that medicines optimisation teams are mainstream in projects and service redesigns from the start, so downstream effects and preventative impact of medicinal interventions, alongside social prescribing, can be considered and ensure best value. - Establish the right governance

ICS should consider establishing a clear board-level medicines lead, supported by appropriate system-wide committees and sub-committees, which help to provide multi-disciplinary expertise to drive transformation across each system. Governance arrangements should ensure a better balance with medicines optimisation teams between time spent on operational and transformational activity. - Build one medicines optimisation team

Alongside developing pharmacy workforce plans that develop innovative and rotational roles, ICBs should consider how they can build awareness of medicines optimisation right across the system including into social care, providing training where necessary. - Harness digital and data

Use shared care records to enable access to medicines information for relevant healthcare professionals across care pathways. Meanwhile, use system-wide data to assess incidence of avoidable harm, specifically inappropriate sodium valproate prescribing, as well as medicines expenditure, to establish an initial baseline in each system to measure success and improvement going forward. - Shared learning and self-improvement

ICSs should be supported to share learning about their respective progress transforming medicines optimisation to drive a process of peer learning and self-improvement. This could include learning on how different systems are delivering improvement in risk assurance; data analytics; digital interoperability; pharmacy workforce planning; development of rotational and cross-sector roles; and integrating medicinal and social prescribing.