Key points

- Innovative medicines transform individual patient lives as well as bringing significant benefits to the UK economy and to society as a whole – through greater patient and carer productivity, NHS productivity and more. It is estimated that the UK economy would achieve £17.9 billion additional productivity gains through the increased uptake of innovative medicines. [1] For the NHS and the wider health and care system to survive and thrive for the benefit of its users, innovation at every stage and in every aspect is not only desirable but necessary.

- Adoption of innovation is challenged by the fact that NHS leaders face ongoing operational pressures every day – asked to meet increasing demand, reduce health inequalities and improve outcomes within constrained resources, while also trying to re-imagine services transformed by a new focus on population health, enabled by partnership working and biomedical innovation.

- Rapid and consistent adoption of evidence-based, innovative medicines is a strategic opportunity for health systems. While medicines themselves have vital clinical benefits in individual treatment, they also have an important broader impact on patients, the NHS, society and the economy.

- However, despite the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and the All-Wales Medicines Strategy Group approving new medicines for use by patients, there is significant geographical and sub-population variation in their usage, leading to millions of patients missing out on proven treatments that would make a huge difference to health outcomes, as well as a failure to realise economic benefits for the NHS and wider society. Figure 2 demonstrates just one example of a therapy area where significant variations in the uptake of innovations exists nationally.

- Improving appropriate uptake and reducing unwarranted variation in the use of innovative medicines presents an important opportunity for integrated care systems (ICSs) in England to achieve their aims not only of ensuring individuals receive the best care possible, but also of reducing health inequalities and supporting broader social and economic development.

- Understanding the barriers to uptake of innovative medicines, and identifying and sharing practical solutions system-wide, are vital to making progress both operationally and strategically. The overarching challenge is to ensure that all health and care system leaders position medicines as a strategic enabler of improved patient outcomes, NHS productivity and efficiencies across the system as well as a clinical intervention for individuals.

- Strategic partnerships between the NHS, patient organisations and industry are also essential in creating a thriving health and life sciences ecosystem that works for patients, society and the economy. Indeed, such partnerships play an important role in enabling the NHS to mature as an innovation partner across value chains and create the conditions required to ultimately tackle unwarranted variation in the uptake of innovative medicines.

Foreword

The development and use of new medicines have been at the heart of human health and progress for hundreds of years. Jenner produced a smallpox vaccine in 1796, and Davy anaesthetics in 1800; Banting made a breakthrough with insulin in 1921, and Fleming penicillin in 1928. Medicines development delivered contraceptives and beta blockers in the 1960s, and anti-virals for HIV in 1996. Vaccines against COVID-19 have transformed the global response to the pandemic since 2020. The ongoing discovery, development and application of innovative medicines has changed the lives not only of millions of individuals but also the global community’s ability to affect population health and wellbeing.

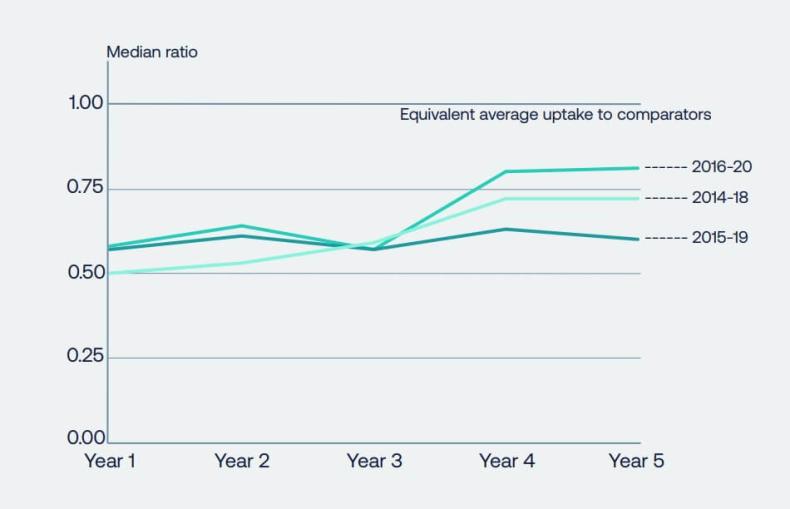

The World Health Organization (WHO) has published a list of essential medicines every two years since 1977. The list has grown from 208 to 479 in 2021, reflecting the importance of innovative medicines and investment in their development during that period. However, access to innovative medicines is inequitable, not only across the globe but within the UK. Where a person lives affects their opportunity to receive the most effective treatment for them. Despite new medicines having NICE approval, there is significant variation in access to them for patients across the UK. Against comparator countries the UK lags behind in uptake (see Figure 1). [2]

The slower and inequitable uptake of innovative medicines contributes to poorer health outcomes for the UK, including for those populations currently disproportionately impacted by disease. For example, UK cancer survival rates lag behind the European average in nine out of ten cancers, with access to cancer medicines being consistently lower than most European countries. It is worth noting that NHS England has opened the reformed Cancer Drugs Fund with more than 100 treatments being funded, and a 2022 report on patient access found that there are five treatments available in England for every four in Europe, and almost a third more cancer drugs in England compared to the European average.[3]

However, data drawn from England has shown that there is a greater premature mortality across numerous diseases than other best performing countries:

- 50 per cent more years lost to ischaemic heart disease than France or Spain

- 60 per cent more years lost to lung cancer than Finland or Sweden

- 50 per cent more years lost to stroke than Austria. [4]

We can change this picture. By working together as system leaders and decision-makers across the health and care services, the pharmaceutical industry, universities and charities to deliver the government’s life sciences strategy, we can ensure that patients are able to access and benefit from innovative medicines – wherever they live in the UK.

In doing so, we can evidence together how improved uptake of innovative medicines can contribute not only to the control of disease but also to reducing the burden of care. And we can coordinate our efforts to embed new medicines in the redesign of service pathways and alongside other new approaches to treatment such as telemedicine, patient-led assessment apps, triage services and at-home testing. All these together will support the NHS and enable its evolution into a more prevention-focused and efficient health system.

On 28 September 2022, the NHS Confederation and ABPI convened a roundtable discussion, bringing together leading experts from across the healthcare policy landscape. That session has helped inform the findings of this report, and we commend its 13 system-level recommendations and further detailed ideas to national and regional health and care leaders.

Matthew Taylor Dr Richard Torbett

Chief Executive Chief Executive

NHS Confederation ABPI

Summary of recommendations

Our 13 specific recommendations, which focus on England, Wales and Northern Ireland, aim to support progress in tackling the unwarranted variation in the uptake of innovative medicines and are listed below.

Health and care government departments across the three nations should:

-

publish a clear national policy statement on improving access to innovative medicines, such as by following the work of the Welsh Government in producing the New Treatment Fund to speed up access to life-improving medicines

- strengthen the role of the NHS as a long-term partner in championing the development and rapid adoption of innovative medicines.

National NHS leaders should:

- improve engagement between the life sciences industry and their national and local colleagues

- improve communication on the role of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the All-Wales Medicines Strategy Group (AWMSG) and changes to specialised national commissioning

- reform rigid pathway structures to ensure all patients have access to innovative medicines from the very beginning of their treatment.

Regional NHS leaders should:

- create data partnership opportunities for ICSs and equivalent structures in Wales and Northern Ireland, industry and other partners

- create and support clinical champions for innovative medicines.

Health and care organisations across the system should:

- create a network at system level to illustrate, champion and leverage the full value of consistent adoption of innovative medicines

- focus efforts on activities that will deliver the greatest impact, in terms of accelerating the introduction and adoption of innovations already in and being brought to the UK by global industry

- continue and build on the good practice of the Medicines Pathway Evaluation Programme

- in England use the new ICS infrastructure as an opportunity to engage and spread good practice

- work hard on improving regional engagement

- embed patient and public involvement and equality, diversity and inclusion strategies throughout all work.

Context

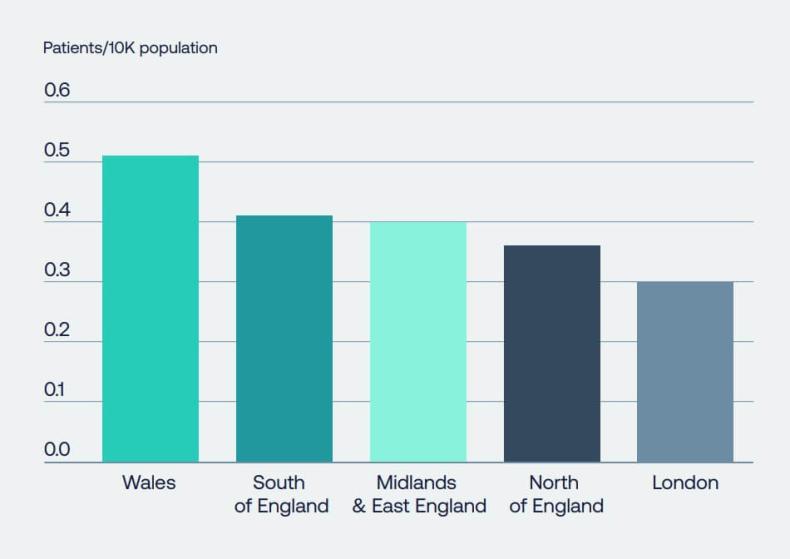

Uptake of innovative medicines remains stubbornly variable across England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Figure 3 provides an overarching breakdown in the variation of uptake at primary and secondary care level and demonstrates the significant gaps in care that patients receive, across England and Wales. [5]

Many major causes of morbidity and mortality disproportionately impact people from lower socio-economic backgrounds. For example, 86 per cent of English northern local authorities have a lower population life expectancy than the England-wide average. [6] Indeed, access to effective treatment among these populations remains disproportionally variable, despite numerous initiatives to address the issue.

The resulting costs from variation in uptake of innovative medicines are significant. A joint ABPI and PwC report published in May 2022 demonstrated that more equitable use of just 13 medicines in line with NICE recommendations across four treatment areas – stroke prevention, kidney disease, asthma and type 2 diabetes – could bring significant economic benefits to the UK, in addition to wider individual and community benefits for patients, carers and families. For these four medicine classes alone, 1.2 million patients are missing out on innovative treatments. [7]

There are real operational pressures on the health and care systems across the UK – continuing or rising demand in part because of the COVID-19 pandemic, shifting demographic need, workforce capacity and skills, constrained funding, external targets and political expectations. It is difficult for those working every day under these ever-present pressures to look beyond the current challenges, to re-imagine services which include using medicines; and to see the uptake of innovative medicines as an opportunity for strategic good. However, innovative medicines do provide this opportunity and there are ways in which appropriate uptake can be encouraged and spread so that all patients who could benefit have an equitable chance to do so, regardless of their geographical location, socio-economic or cultural background.

Building on the discussions we had during our roundtable in September, this report offers an analysis of the barriers and drivers of variation in uptake, and then provides some practical insights into what can and could work to tackle these challenges. It sets out 13 actionable recommendations for system leaders at both national and regional levels to take forward. The appendix provides details of the event, along with links to further reading and additional case studies.

Our report also draws on four tangible case studies from across the UK, which demonstrate the critical role that industry and NHS partnerships can play in tackling variations in uptake and ultimately help improve health outcomes for both the NHS and patients. While these case studies represent examples of good practice at a localised level, not everyone is able to benefit from these changes and there is a need to scale industry collaboration to help reduce unwarranted variation nationally.

Figure 1: Uptake in the UK continues to be below the average of comparators. This graph represents UK uptake (days of therapy) of new medicines per capita, as a ratio of comparator countries average. Source: Office for Life Sciences.

Figure 2: Variance in uptake across NHS trusts in England vary considerably when broken down based on disease area. When comparing the uptake of three types of medicines related to diabetes, there is more than 51 per cent variance between trusts. Source: NICE technology appraisals in the NHS in England (innovation scorecard), to June 2022. [9]

Figure 3: Of the sampled regions across the UK, we observed a 59 per cent variance between London and Wales in the uptake of NICE-approved medicines. We also observed a variance of 26 per cent in primary care and 20 per cent in secondary care. (Source: IQVIA).

Structural barriers behind unwarranted variation in uptake

A number of root causes lie behind unwarranted variation in uptake, identified as:

- The absence of a system-wide secondary prevention narrative which encompasses the importance of early and effective use of innovative medicines to stabilise patients and delay or stop disease progression.

- Limitations in the ability of local health and care systems to address disparities in uptake by supporting community awareness of what is available to patients.

- Constrained capacity in the workforce both in relation to an ability to develop and improve pathways, and in more simple administrative burdens associated with the implementation of new medicines.

- Issues with accessing timely, accurate and personalised diagnosis and the associated detrimental impact on uptake. These issues are illustrated by case study 1 which analyses the substantial regional variation in the uptake of CAR T patient treatments. This case study demonstrates just one example of a therapy area where geographical disparities can have a significant impact on the quality of care a patient can expect to receive based on where they live.

- Complexities in measurement and data hampering efforts to demonstrate impact in healthcare, coupled with;

- Insufficient understanding of strategic benefits beyond a simplistic cost – benefit calculation in relation to new medicines.

The influence of conservatism in healthcare planning and delivery was discussed, reflecting that at times the NHS can appear to be uncomfortable with innovation, and that it can be seen as a risk or an additional burden on already limited resources, rather than a solution to shared challenges.

Unconscious bias, which is shown to have a significant influence on attitudes and behaviours is also a barrier to uptake. Disparities that exist in various groups receiving referrals and treatment can be impacted negatively by unconscious bias influencing key decisions, patient choices and contribute to health inequities. Unconscious bias can also be seen in ageist assumptions about treatment appropriate for seniors (the ‘what do you expect at your age’ commentary).

Another barrier identified is that of some cultures and behaviours among clinicians, administrators, commissioners, politicians, and indeed patient and social communities, all of which can demonstrate fear of change and inability or unwillingness to take a holistic, whole-person and broader societal view.

Finally, the lack of a clear national policy statement from the UK government on how improved access to innovative medicines could significantly reduce unwarranted variation in standards of health and care, improve health outcomes, reduce health inequalities, tackle patient backlogs, contribute to economic growth and support delivery of NHS England’s Long Term Plan was identified. If this were in place, it could stimulate the whole system to take focused action.

Operational barriers to wider and more consistent uptake of innovative medicine

A range of operational issues act as barriers to the uptake of innovative medicines, including:

- Failure by NHS organisations to consider ‘upstream’ investment in innovative medicines at a strategic level to drive secondary prevention, improved outcomes and system efficiencies.

- A lack of knowledge and awareness of the medicines themselves and their potential to support the delivery of strategic population health management goals.

- Continuous capacity pressures in clinical teams and organisations.

- Lack of ‘headspace’ and time in the system at individual and organisational level to engage with new solutions.

- Rigidity in pathway structures, often requiring patients to fail on several older treatments before innovative approaches are considered.

- Administrative processes, such as doctors in Northern Ireland having to complete a ‘cost per case’ form for every patient requiring any innovative, NICE-approved medicines, which represents not only a barrier to uptake but a questionable use of valuable clinical resource.

- Commissioning decisions with a traditional or narrow focus on acquisition cost of medicines, as opposed to considering pathway value.

- Lack of understanding or focus on the opportunity cost of not accessing innovative medicines.

- Limited capability to measure impact on patients, the NHS itself and broader society.

The lack of high-quality data being consistently captured, analysed and acted upon is perceived as both an operational and strategic barrier, preventing an effective correlation between inputs, patient outcomes and system efficiencies.

Potential solutions and achieving their spread and scale for patient and system benefit

The next two chapters focus on how a collaborative and creative partnership across industry, the NHS and local communities, can create a positive working environment that can improve the uptake of medicines and result in better health outcomes for communities.

Further examples of significant improvement can also be found when industry has partnered closely with thought leaders and the NHS to help drive up awareness around disease areas at a grassroots level. Case study 3 highlights the role that MSD’s ‘Do it For Yourself’ campaign played in increasing two-week wait referral (2WW) cancer referral rates across socio-economically deprived regions in England. It also emphasises how such an approach can successfully take place across geographically diverse parts of England and provides a solid blueprint for how similar initiatives can be expanded system wide.

Spread and scale in the uptake of guideline-directed therapies beyond individual organisations would be assisted by a systemwide approach to improving evidence-based medicines use, factoring in pathway improvement and design, bolstered by a strengthened culture shift with medicines not being seen only through a cost lens, but instead using a broader return on investment approach, taking a preventative and wholepathway view. Indeed, case study 4 shows how Boehringer Ingelheim UKIE’s collaboration with the Leeds Teaching Hospital NHS Trust in optimising its cardiometabolic pathway can improve medicine use and empower patients with the tools needed to adopt healthier lifestyles. The value of this local case study in delivering better quality outcomes is a useful area of consideration for future scaling at a national level.

An important factor identified in the successful spread and scale of innovation is achieving alignment on the problem itself. Without broad agreement on the practical and strategic problem the health system is trying to solve, uptake of innovative medicines is likely to continue to experience unwarranted variation. The power of collective focus and action has been demonstrated by the NHS and partners in the COVID-19 response, and in specific disease areas, including Hepatitis C. Strengthening the collective voice of the NHS and system partners in relation to the impact of innovative medicines is crucial to achieving spread and scale across the system for patient and system benefit.

The role of ICSs in England in helping to coordinate this collective voice is also fundamental, and systems can use new healthcare system infrastructure to engage and spread good practice. They have the potential to help health systems to think differently about prevention and to establish clear feedback loops to ensure prevention is not only seen as having a longer-term impact.

Regional NHS England teams are also considered to be an important part of this collaboration; supporting consistency and alignment in efforts to improve uptake in the interest of local communities.

Cultivating and supporting clinical champions to achieve spread and scale was also highlighted as another important opportunity both for system wide operational and cultural change.

Moreover, genuine citizen involvement will need to be a cornerstone of these efforts, with user-centric innovation key to successful and sustainable spread and scale. This is true throughout the process, from increasing engagement in early-stage development and diversity in clinical research trials, to driving awareness and patient choice in health treatment and care decisions.

During the cross-sector roundtable that contributed to this report, the following specific ideas to accelerate and encourage uptake of innovative medicines were also put forward for consideration:

- Develop a ‘comply or explain’ framework for NHS organisations which show disproportionately low use of NICE-approved innovative medicines relative to their eligible patient populations (using ICS level published data) and provide support to them to tackle local issues causing the disparity.

- Incentivise uptake specifically as part of system-level strategies tackling health inequalities.

- Give practical support to ICSs to disaggregate, interpret and share data on uptake of and outcomes from innovative medicines.

- Give health and care regulators (such as the Care Quality Commission and Health Inspectorate Wales) a greater mandate in scrutinising uptake of innovative medicines.

- Position behaviour shifts as a change process not simply a communication task, and support and resource accordingly

Case studies

Provided below are four industry and NHS partnerships that demonstrate the importance of the collaboration across the health system to improve patient outcomes.

While several case studies exemplify the success that can occur when partnerships are able to thrive, (particularly case studies 2, 3 and 4) such achievements only occur at a localised level and not all patients are able to benefit from them. It is therefore important that these positive working relationships are scaled up nationally to help reduce unwarranted variations. A failure to drive down these disparities can result in a significant imbalance in the quality of health outcomes that patients receive between regions, as illustrated by case study 1.

Case study 1: Addressing regional variation in CAR T patient treatment – Gilead

CAR T-cell therapy is a specialist and advanced class of cell and gene therapy treatments that use genetically engineered T-cells to recognise and target cancers. Gilead Sciences has been proud to partner with NHS England and local centres alongside Novartis in supporting England to make CAR T therapy available from 2018, initially for patients with a form of leukaemia, and subsequently for patients with a type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. [10] CAR T was subsequently made available for use in Scotland and Wales. [11]

CAR T therapies have now been available to patients in England for nearly four years and are delivered across 14 specialist sites in the UK for adult patients as of October 2022. The NHS’s rapid adoption of these personalised therapies has been impressive, demonstrating agility, ambition and collaboration in overcoming the wide range of unique challenges these complex therapies present.

However, data suggests that while CAR T has been routinely available to patients in England for coming up to four years, significant variation in access remains. In the case of diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL), hospital episodic statistics (HES) data suggests that there may be inequality in access to CAR T for patients from areas with higher levels of deprivation. In the period from 2019 to March 2022, this data shows that only 11.7 per cent of CAR T-treated patients came from the most deprived quintile of the population, compared to 23.8 per cent from the least deprived quintile. [12] While this deprivation quintile variation does also exist for patient care across the entire DLBCL patient population, it appears to be more pronounced for patients infused with CAR T.

This data also suggests that wider regional inequality in access to CAR T may exist. In 2021, there appeared to be fewer CAR T infusions for patients diagnosed in the Southwest and in a belt across the North than in other areas. [13]

Based on analysis of HES data and Gilead’s own internal data, Gilead are concerned that patients in certain areas of the country appear to face challenges in access to CAR T therapies. HES data from 2019 to 2022 may suggest that no or very limited numbers of patients in either the Northeast region near Hull or areas of the Southwest including Cornwall have been treated with CAR T since it was made available. [14] There are also indications that treatment rates have recently improved in certain areas of the Northeast and Southwest, although this is not yet reflected in the available data.

If this data is accurate, Gilead are concerned it appears to be mirrored in wider health disparities facing people in both the Northeast and Southwest – who tend to suffer from poorer health outcomes and wait longer for care than those in other areas of the country:

- Life expectancy is 12.7 years lower for men and 10.2 years lower for women in Kingston upon Hull than in England’s least deprived areas. [15] In Cornwall, the under 75 mortality rates from cancer is 127.1 per 100,000 people – around the national average, but much worse than the best areas of the country which have a rate of 87.4 per 100,000. [16]

- Cancer waiting times in Hull CCG are also higher than those in other areas of the country, with 57.07 per cent of patients receiving treatment within the targeted 62-days from referral compared to a national target of 85 per cent. [17] In NHS Kernow CCG – the NHS area that covers Cornwall – 73.63 per cent of patients are seen within 62 days. [18]

As such, Gilead would welcome the opportunity to discuss the challenges captured above in further detail, and to explore how industry can collaborate with local teams to ensure equitable access to innovative treatments across the country.

Case study 2: Service transformation – halving time in hospital for patients with soft tissue sarcoma – Lilly UK

Following the addition of a new chemotherapy to the treatment standards for patients with soft tissue sarcoma (STS), The Beatson West of Scotland Cancer Centre worked with Lilly UK to halve the amount of time patients spent in hospital and free up consultant time which improved the efficiency of their chemotherapy clinic.

Under a Joint Working Agreement with Lilly UK, the project took a Lean Six Sigma approach to identify areas for improvement, which would implement a new nurse-led service to reduce the length of time patients spent in clinic.

The aim of the project was to identify where delays were occurring. Data was collected from key points in the care pathway, and this helped map out the minimum possible process time so that this could be used as a baseline target. Following this, the project set up a new Systemic Anti-Cancer Therapy (SACT) service for patients, removing them from the general clinic, therefore freeing up capacity in the general clinic and reducing patients time in hospital. The project also measured patient satisfaction with the new service, as well as efficiencies made in having a new nurse led service as opposed to one led by consultants.

The programme resulted in a series of positive changes for the SACT service. Total patient time in hospital was reduced by more than a half from 8 hours 31 minutes on average, to 3 hours 57 minutes. This is a reduction of 4 hours 34 minutes, and a equates to a reduction of 53.6 per cent. For patients whose treatment was authorised the day prior to attending for treatment, the time in hospital was reduced further, to 3 hours 18 minutes. This is a reduction of 61.3 per cent on preproject time in hospital. Surveys completed by 12 patients also showed a high rate of satisfaction with the new service.

The project highlighted that the use of process mapping was an effective tool in improving clinical efficiencies, that could be benefit in reducing patient numbers in line with new ways of working following the COVID-19 pandemic. It also demonstrated the critical role that industry can play in sharing skills to ultimately, improve patient care and their experience in the NHS.

Better for patients:

- Total patient time in hospital was reduced by more than a half – from 8 hours 31 minutes on average, to 3 hours 57 minutes.

- For patients whose treatment was authorised the day prior to attending for treatment the time in hospital was reduced further, to 3 hours 18 minutes.

Better for the NHS:

- The resultant reduction in hospital waiting times and transition to a nurse-led service, helped free up capacity for consultants for other NHS care. [18]

Case study 3: ‘The ‘Do It For Yourself’ campaign supports patients to seek help and respond to drop in referral rates – MSD

The ‘Do It For Yourself’ campaign was designed to support lung cancer disease awareness within some of the most socio-economically deprived regions across England in areas which exhibit some of the highest levels of disease burden of lung cancer as well as the steepest declines in patient presentation when the pandemic began. These included Cheshire and Merseyside, Greater Manchester, Lancashire and South Cumbria, North East and Cumbria, Peninsula, South East London, South Yorkshire and Bassetlaw, and West Yorkshire and Harrogate. This campaign was designed and implemented with the support of a number of cancer alliances, professional organisations and charities.

The campaign was successful in creating a visual concept and message which resonated with MSD’s target audience, and which was delivered through a multi-channel approach, enabling a significant proportion of MSD’s target audience to have seen or have heard the campaign. From a stakeholder perspective, feedback confirms the campaign helped fill a gap, in providing many local cancer alliances with valuable resources to support with targeted awareness raising at a highly volatile time; helping them to build further visibility and credibility within their local communities, as well as enhancing connectivity between national and regional organisations.

Moreover, while behaviour change campaigns can typically require many years to establish and measure their impact, initial feedback and data support the value of this particular ‘rapid development’ public health campaign approach. While there are numerous factors that prevent MSD from drawing direct, definitive conclusions in terms of what percentage of the public exposed to the campaign subsequently followed up on any symptoms. On average, regions tackling greater deprivation are rebounding from the pandemic more slowly. Looking at the trend for the whole year and comparing the most deprived regions with the rest of England, the trend of total numbers of patients returning to care has been slower than in less deprived areas.

Ultimately, recovery from the impact COVID-19 has had on lung cancer will require ongoing and dedicated efforts, that consider regional variations and requirements. However, insight driven public health campaigns, developed and deployed in partnership with local organisations and representatives can have a powerful protective and supportive role to play in facilitating and expediting this process.

Better for patients:

- When looking at the two-week wait referral figures across a two-month period before the campaign took place (April and May 2021) versus figures for the month of the campaign and month directly following the campaign (July and August 2021), there was an increase in the number of 2WW referrals within six of the eight cancer alliances where the campaign took place.

- For the same time periods, when looking at the percentage change in 2WW referrals, nationally England remained stable. Cancer alliances where the campaign took place showed a 5.4 per cent increase in referrals, which is in line with the observed national trend leading up to the campaign of 5.2 per cent.

Better for the NHS:

- By acting swiftly to design and implement a lung cancer symptom awareness campaign while the NHS was focusing on the pandemic response, ‘Do It For Yourself’ was able to play a role in striving to positively impact the decline of lung cancer referrals during a critical time. [19]

GB-NON-06792

Case study 4: Optimisation of cardiometabolic pathway – Boehringer Ingelheim UKIE

Working with Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Boehringer Ingelheim UKIE established a new innovative cardiometabolic clinic. Around 1/4 of patients who suffer a heart attack have type 2 diabetes (T2D). [20] The presence of diabetes increases the risk of death by >2.5 times when compared to heart attack patients without the disease. [21] The pharmacist-delivered clinics scheduled for 6-8 weeks post heart attack, are a patient-centred approach to reducing risk.

The aim of the clinic is to:

- Optimise and reduce the cardiovascular risk factors among patients with T2D and cardiovascular disease.

- Provide better support for patients, including education and self-management.

- Enable patients discharged from clinic to have better diabetes control through improved medication adherence and medication optimisation by providing strategies to address a number of factors that may impact an individuals’ adherence to their medications.

- Enable timely interventions to reduce the need for further treatment escalation and reduced hospital stays.

- Offer patients with T2D post-MI, the use of guidelinedirected cardio-protective diabetes agents.

- Identify the training needs to develop advanced pharmacists who can run such clinics as part of a multi-disciplinary team.

Since its founding, the ‘one-stop clinic’ has helped reduce the waiting list burden for diabetes review. While some patients still need a review by a diabetes specialist, many receive optimisation of their cardio-renal-metabolic (CaReMe) medicines and risk factors without needing a referral to the diabetes service. Additionally, a reduction in patient visits required in both primary and secondary care. The combination of face to face and a virtual clinic approach is convenient for patients and reduces the pressure on the outpatient services.

Interim results demonstrate the importance of a CaReMe approach in cardiovascular risk reduction with patients achieving improvements in their HbA1c, lipid profile and BP control as well as a fall in BMI.

Better for patients:

- Thanks to the success of this clinic, patients were empowered with the tools needed to adopt healthier lifestyles, e.g., 38 per cent of patients who attended clinic were provided with a home blood pressure monitor to better optimise BP, and 65 per cent of smokers were provided smoking cessation advice including the prescribing of smoking cessation therapy.

- With 100 per cent of patients surveyed expressing that their concerns relating to heart/diabetes health were addressed.

Better for the NHS:

- Improved workforce utilisation – upskilling pharmacists allowing consultant physicians to manage more complex patients.

- HCP skills (pharmacist) matched to patient needs – a high patient need exists to uncover barriers to adherence, provide health education and medicine optimisation.

- Improved compliance with guidelines – prescribing of guideline recommended pharmacological therapies in line with NICE and local guidelines.

- Optimising therapy for the multimorbid patient – including recommended therapies for post MI secondary prevention, diabetes, and renal disease where identified.

Recommendations

These recommendations flow from the commentary outlined above and are offered as practical and experience-based calls to action for system leaders across the UK’s health and care landscape. Our 13 specific recommendations to support progress in tackling the unwarranted variation in uptake of innovative medicines are set out below.

Health and care organisations across the system should:

- Create a network at system level to illustrate, champion and leverage the full value of consistent adoption of innovative medicines, ensuring that innovation adoption is not seen as a burdensome ‘add on’, but rather a central part of delivering shared objectives for patient benefit, efficiency, and reduction in health inequalities.

- Focus efforts on activities that will deliver the greatest impact, in terms of accelerating introduction and adoption of innovations already in and being brought to the UK by the global industry, with industry involvement viewed as an integral component of partnership from initial planning stages through to implementation and performance monitoring.

- Continue and build on the good practice of the Accelerated Access Collaborative’s Medicines Pathway Evaluation Programme which has ensured a well formulated scope and a programme of work for identifying and addressing system barriers to adoption and uptake.

- In England use the new ICS infrastructure as an opportunity to engage and spread good practice, with system partners working together to achieve spread and scale in the uptake of innovative medicines.

- Work hard to ensure full regional engagement, including by ensuring that industry and ICS leaders can input in the development of guidance to support ICSs in delivering on the research mandate (as laid out in the Health and Care Act 2022).

- Embed public and patient involvement and equality, diversity and inclusion strategies throughout the programme at strategic and operational levels to ensure it reflects patient and society priorities and needs.

Health and care government departments across the three nations should:

- Publish a clear national policy statement on how improved access to innovative medicines could significantly reduce unwarranted variation in standards of health and care, improve health outcomes, reduce health inequalities, tackle patient backlogs, contribute to economic growth and support delivery of NHS long-term plans.

- Strengthen the role of the NHS as a long-term partner in championing the development and rapid adoption of innovative medicines, through a broader return on investment approach; taking a preventative, whole-pathway and population health view; working to dismantle barriers to conducting clinical trials and working more closely with the life sciences industry in the early stages of medicine development.

National NHS leaders should:

- Improve engagement between the life sciences industry and their national and local colleagues, to make easier for the NHS to know about development in medicines, and how these can be implemented in care pathways.

- Improve communication on the role of NICE and AWMSG and changes to specialised national commissioning.

- Reform rigid pathway structures so that patients are not required to fail on older medicines before innovative approaches are considered, so that they can have access to the right treatment for them the very beginning.

Regional NHS leaders should:

- Create data partnership opportunities for ICSs and equivalent structures in Wales and Northern Ireland, industry and other partners, to share and disaggregate data better in order to draw out and implement actionable insights.

- Create and support clinical champions for innovative medicines providing outcome focused leadership from within the NHS and enabling the progress from strategy to delivery and impact.

Appendix

Details of roundtable discussion

A roundtable discussion was hosted by the NHS Confederation and ABPI and took place online on Wednesday 28 September 2022. Participants came from the NHS, pharmaceutical and medical research charity sectors. They were provided with background reading and a series of questions to prompt their own thinking; and were invited to share case studies from their own environments.

Through a structured discussion, participants identified barriers to system-wide uptake of innovative medicines, drivers of unwarranted variation, shared successes in tackling these challenges and discussed how good practice could be adopted system-wide and what would need to change to enable this.

We recognise that Scotland is not represented by the NHS Confederation and as such, attendees of the roundtable focused on their respective organisations and health systems.

Attendees

- Dr Dianne Addei, Senior Public Health Adviser, National Healthcare Inequalities Improvement Programme, NHS England

- Sue Brown, Chief Executive, Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Alliance (ARMA)

- Colette Goldrick, Executive Director – Strategy, Research and Partnerships, ABPI

- Linda Honey, Director of Pharmacy and Medicines Optimisation, Surrey Heartlands ICS

- Todd Manning, Vice President and General Manager, AbbVie

- Matthew Taylor, Chief Executive, NHS Confederation

- Sarah Woolnough, Chief Executive, Asthma UK and the British Lung Foundation.

The discussion was chaired by Hilary Reynolds CBE (former chief executive of the Association of Medical Research Charities), and supported by Donal Sutton and Amy Swanborough from the NHS Confederation; and Brian Duggan and Victoria Bates from ABPI.

Further reading

- Transforming Lives, Raising Productivity – May 2022, PwC report, commissioned by ABPI

- Local Uptake of NICE Approved Medicines in England and Wales, A Summary of Insights – June 2022, IQVIA report, commissioned by ABPI.

References

- Transforming lives, raising productivity: Is the UK missing out on the full potential of innovation medicines? Available at: https:// www.abpi.org.uk/media/5frnryxy/transforming-lives-raising-productivity-v4-may.pdf (Accessed: November 28, 2022).

- Life science competitiveness indicators 2022 GOV.UK. Available at:. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/ life-science-sector-data-2022/life-science-competitiveness-indicators-2022 (Accessed: November 28, 2022).

- IQVIA (2022), EFPIA Patients W.A.I.T. Indicator 2021 Survey (updated July 2022), https://www.efpia.eu/media/676539/efpiapatient-wait-indicator_update-july-2022_final.pdf (Accessed: January 2023).

- Transforming lives, raising productivity: Is the UK missing out on the full potential of innovative medicines? Available at: https:// www.abpi.org.uk/media/5frnryxy/transforming-lives-raising-productivity-v4-may.pdf (Accessed: November 28, 2022).

- Transforming lives, raising productivity: Is the UK missing out on the full potential of innovative medicines? Available at: https:// www.abpi.org.uk/media/5frnryxy/transforming-lives-raising-productivity-v4-may.pdf (Accessed: November 28, 2022).

- IQVIA (2022) Local Uptake of NICE Approved Medicines.

- University of York (2019) Researchers to tackle worsening North-South health divide. 18 July 2019.

- Transforming lives, raising productivity: Is the UK missing out on the full potential of innovative medicines? Available at: https:// www.abpi.org.uk/media/5frnryxy/transforming-lives-raising-productivity-v4-may.pdf (Accessed: November 28, 2022).

- Digital, NHS (2022) NICE technology appraisals in the NHS in England (innovation scorecard), to June 2022, GOV.UK. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/nice-technology-appraisals-in-the-nhs-in-england-innovation-scorecard-to-june-2022 (Accessed: November 28, 2022).

- NICE, NICE recommends a CAR T-cell therapy for adults with some types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, 2019.

- Scottish Medicines Consortium. SMC recommends CAR T-cell therapy for adults with some types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, 2019.

- Kite analysis: DLBCL CAR T health inequality and penetration analysis, June 2022.

- Kite analysis: DLBCL CAR T health inequality and penetration analysis, June 2022.

- NHS Digital: Hospital Episode Statistics analysis via reuse licence (Harvey Walsh), 2022.

- Public Health England, Kingston upon Hull, Local Authority Health Profile 2019, March 2020.

- Public Health England, Cornwall, Local Authority Health Profile 2019, March 2020.

- NHS England, Commissioner based Cancer Waiting Times for Q1 2022-23 Provisional, August 2022.

- NHS England, Commissioner based Cancer Waiting Times for Q1 2022-23 Provisional, August 2022.

- Lilly UK case study, 2022.

- 19. MSD, Do It Yourself Campaign Evaluation Report (2022) Available at: https://www.msd-uk.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/43/2022/02/Do-It-For-Yourself-Campaign-Evaluation-Report-Jan-2022.pdf (Accessed: November 28, 2022).

- Unpublished data – Dr Rani Khatib.

- Haffner et al. N Engl J Med 1998;339:229–34 https:// www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejm199807233390404 (Accessed: November 28, 2022).

About us

NHS Confederation

The NHS Confederation is the membership organisation that brings together, supports and speaks for the whole healthcare system in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. The members we represent employ 1.5 million staff, care for more than 1 million patients a day and control £150 billion of public expenditure. We promote collaboration and partnership working as the key to improving population health, delivering high-quality care and reducing health inequalities.

For more information visit www.nhsconfed.org

Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI)

The ABPI exists to make the UK the best place in the world to research, develop and use new medicines and vaccines. We represent companies of all sizes who invest in discovering the medicines of the future. Our members supply cutting edge treatments that improve and save the lives of millions of people. We work in partnership with Government and the NHS so patients can get new treatments faster and the NHS can plan how much it spends on medicines. Every day, we partner with organisations in the life sciences community and beyond to transform lives across the UK.

For more information visit www.abpi.org.uk