Key points

- Research conducted by public bodies has shown that COVID-19 has had a greater impact, both directly and indirectly, on people who share certain protected characteristics (such as belonging to particular ethnicities or age categories, having a disability, or being women or from the LGBTQ+ community). Health and care services have a major role to play in both identifying the extent of these impacts as well as working together to reduce them.

- This report showcases examples of health and care systems across the country devising innovative approaches to mitigate the direct effects of COVID-19, through targeted vaccination campaigns, and support for people to recover from indirect impacts, through wellbeing and support programmes.

- These examples evidence that barriers came down during the pandemic to protect staff, patients and resources both within the NHS, and between NHS organisations and external partners in local government and the voluntary sector. They also show that tackling health inequality in an inclusive way is possible.

- The NHS and its partners must continue to gather data both on the direct and indirect impacts of the pandemic on people with different protected characteristics, and on the effectiveness of different programmes in addressing these impacts.

- Building on the achievements of the past two years, we must fund voluntary and community sector partners and put processes in place to consolidate partnership working (both within the NHS and between NHS organisations and other stakeholders) to drive continued progress in reducing inequalities affecting people with protected characteristics.

Introduction

During the two years since COVID-19 emerged as a global threat, it has become increasingly clear that some groups have experienced worse outcomes from the virus itself, and also as a result of measures taken to slow the spread of the disease.

Where inequalities are already known to exist, it is important to monitor new threats such as COVID-19, so that if an exacerbation of these existing inequalities is observed, health and care leaders have an opportunity to respond quickly.

Legislation exists in the UK to protect people with different ‘protected characteristics’ from discrimination in places of work and where they access services. They can cause people to experience discrimination in the workplace and in their daily lives. Having regard to these protected characteristics is helpful when considering how policies affect different groups of people from an equalities perspective.

This report maps existing research into COVID-19 inequalities onto some of these protected characteristics, showing how the pandemic has interacted with them. It then showcases four case studies of how different health and care systems have put in place interventions to respond to these inequalities when designing their COVID-19 response.

It is important to note that although this report does not address all protected characteristics, this does not mean that people with protected characteristics not discussed here have not been adversely affected by the pandemic. The report’s aim is to highlight some areas in which evidence has already been gathered about the pandemic’s impacts and to illustrate how the protected characteristics can be used as a framework for understanding the differential impact of COVID-19 on different groups of people.

Background: the UK Equality Act 2010 and its relevance to COVID-19

The Equality Act 2010 is a key piece of UK anti-discrimination legislation. The Act is designed to protect different groups of people from discrimination in the workplace and in accessing services, and describes how different forms of discrimination can affect these groups.

The Act sets out sets out nine protected characteristics. These are characteristics where there is specific provision in the Equality Act to guard against direct and indirect discrimination.

Direct discrimination is when someone is discriminated against because they have a protected characteristic, whereas indirect discrimination occurs when rules or arrangements applying across the board are in practice unfair to a people sharing a particular protected characteristic. [1]

Viewing the impact of COVID-19 through the lens of these protected characteristics can be informative in understanding how the pandemic has impacted some groups of people who are at potential risk of discrimination.

In producing this report, we have identified research highlighting the impact of COVID-19 on black, Asian and minority ethnic groups, people with a disability, women and pregnant women.

The next part of this report summarises the findings for each of these groups.

Box 1: Protected characteristics in the Equality Act 2010

- Age

- Disability

- Gender reassignment

- Marriage and civil partnership

- Pregnancy and maternity

- Race

- Religion or belief

- Sex

- Sexual orientation

Source: Equality and Human Rights Commission

Provisions for carers

Carers looking after someone who is elderly or disabled are protected by law against direct discrimination or harassment because of their caring responsibilities. This is because they are counted as being associated with someone who is protected by the law because of their age or disability.

COVID-19 and people with black, Asian and other minority ethnicities

There is already a significant body of evidence showing that from the start of the pandemic, belonging to a black or minority ethnic (BME) group has been associated with an increased risk of contracting COVID-19, experiencing more severe symptoms and higher rates of death.

Research carried out by Public Health England in 2020, prior to the launch of the COVID-19 vaccination campaign, explored the extent to which ethnicity impacted on risk and outcome. This revealed that people of Bangladeshi ethnicity had twice the risk of death compared to people with white British ethnicity, while people of Chinese, Indian, Pakistani, other Asian, Caribbean and other black ethnicity had 10-50 per cent higher risk of death than people of white British ethnicity.

Moreover, death rates for black and Asian ethnic groups were higher than for white ethnic groups, in contrast with previous years when all-cause mortality rates were lower in black and Asian ethnic groups. These analyses did not account for the effect of occupation, co-morbidities or obesity, all of which are associated with the risk of acquiring COVID-19, of dying from it or both. But the report emphasises that other evidence has shown that when co-morbidities are included, the difference in risk of death between ethnic groups among hospital patients is greatly reduced. [2]

Co-morbidities

Stakeholders participating in Public Health England’s research suggested that rather than creating new health inequalities, the pandemic had exacerbated existing inequalities affecting BME groups in the UK. [3] This finding is supported by evidence gathered by the House of Commons’ Women and Equalities Committee in 2020, in an inquiry into the impact of COVID-19 on people from BME groups.

Co-morbidities are known to increase the likelihood of more severe COVID-19 and the Women and Equalities Committee heard evidence that the prevalence of hypertension is higher among black African and Caribbean groups than in the white population, while South Asian groups may experience a higher risk of cardiovascular disease.

People in Asian and black ethnic groups have been found to develop diabetes at a younger age than people in white ethnic groups on average, and some BME people are susceptible to obesity-related diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, at a lower weight than white populations. The committee has called for the prioritisation of primary prevention work and the expansion of eligibility for NHS health checks so that people from a BME background are invited to attend a health check from age 25. [4]

Pre-existing inequalities

The committee emphasised that throughout the pandemic, black, Asian and minority ethnic people have been acutely affected by a large number of pre-existing inequalities, ranging from health to employment, accessing Universal Credit, housing and the ‘no recourse to public funds’ policy. Many of these underlying inequalities made the impact of the pandemic far more severe for BME people than for white counterparts, the inquiry found. [5]

Cultural competency and community networks

The Women and Equalities Committee also highlighted the importance of guidance that is culturally competent in communicating with people from BME backgrounds. Inquiry witnesses reported that work with community groups and focus groups was essential to iron out problems such as poorly-targeted communications and a lack of specific terms in some languages for important concepts related to the pandemic.

A compounding issue was that the lockdowns had meant the closure of community networks that some BME people rely upon to source information. The committee highlighted the value of schemes such as the government’s Community Champions initiative in addressing these problems. [6]

Housing conditions

A final factor covered by the COVID-19 inquiry was housing conditions. Two issues were relevant here: BME people were found to be more likely to live in overcrowded homes, and more BME people live in multi-generational homes where people aged over 65 live with children aged under 16. In both cases, social distancing, self-isolation and shielding is more difficult, increasing the potential for transmission of the virus within households. [7]

Employment and benefits

Issues relating to employment and benefits also emerged as important factors in the Women and Equalities Committee inquiry into COVID-19 and BME people. The inquiry heard that BME people were more likely to be health and social care keyworkers, and slightly more likely to be working in sectors such as restaurants, gyms and non-essential retail that had experienced a shutdown during the initial national lockdown.

Moreover, BME people were more likely to be in insecure work, which for some means that they will not be able to access statutory sick pay, and “disproportionately over-represented” in zero-hours and insecure contracts. The inquiry saw some evidence of people on zero-hours contracts being refused furlough payments. When as a consequence BME people need to apply for benefits under the Universal Credit system, digital barriers to access can pose a problem for claimants in registering on the system. [8]

COVID-19 and sex, pregnancy and maternity

In 2021, the Women and Equalities Committee undertook a separate inquiry into the gendered economic impact of COVID-19. It found that the government’s priorities for recovery were “heavily gendered in nature”, with investment plans skewed towards male-dominated sectors, running the risk of exacerbating existing inequalities between men and women. [9]

The inquiry found that women were over-represented in the group of people ineligible for statutory sick pay and called for a government study into the adequacy of and eligibility for statutory sick pay, along with an equity impact analysis, as well as the extension of redundancy protection to pregnant women and new mothers. [10]

Higher risk of severe disease

Research carried out in Scotland found that while pregnant women were not at increased risk of contracting COVID-19 compared with non-pregnant women, they were at higher risk of severe disease. Pregnant women were more likely to be admitted to intensive care, to receive invasive ventilation and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) and to die. COVID-19 in pregnancy was also associated with an increased risk of pre-eclampsia, pre-term birth and stillbirth. [11]

Although pregnant women were not included in COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials, subsequent data suggests that vaccine effectiveness is broadly similar for pregnant and non-pregnant women, but researchers found uptake among pregnant women was low in Scotland during the study period, and that severe complications known to be associated with COVID-19 in pregnancy were more common in unvaccinated pregnant women than in pregnant women. [12]

COVID-19 and disability

The Equality Act defines a disability as a physical or mental impairment with a long-term adverse effect on day-to-day activities. People with disabilities in the UK have faced a greater risk of illness and death than those who do not have a disability during the pandemic. Analysis of deaths by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) revealed that between the start of the pandemic and late November 2020, disabled people accounted for six in ten deaths involving COVID-19.

Higher rate of death

Age standardised death rates involving COVID-19 for people aged between 30-100 showed those people who had reported that they had a disability in the 2011 census had a statistically significantly higher rate of death during this period, and more-disabled people had a statistically significantly higher rate of death than less-disabled people. [13]

People with a learning disability died of COVID-19 in much higher numbers than the general population at the beginning of the pandemic. Data gathered by the Learning Disabilities Mortality Review programme shows that between February and June 2020, the death rate for people with learning disabilities was 2.3 times higher than the rate in the general population over the same period.

When this is adjusted to account for under-reporting, the figure is 3.6 times higher than in the general population. During the peak three weeks of the early part of the pandemic, deaths from all causes for people with learning disabilities were three times the average for the corresponding period in the two previous years. For the general population, deaths were twice as high. The disparity was much larger in younger age groups. [14]

Impact on wellbeing

Research conducted by the ONS between March 2020 and December 2021 revealed that disabled people experienced very high levels of worry about the effect the pandemic was having on their lives, with 91 per cent reporting being very or somewhat worried in March 2020. This had decreased to 72 per cent by December 2021, but this was still higher than the lowest level of 59 per cent in June 2021. [15]

In May 2021, disabled people continued to have on average poorer wellbeing ratings than non-disabled people across four wellbeing measures (life satisfaction, feeling that things done in life are worthwhile, happiness and anxiety). Disabled people reported feeling stressed or anxious (79 per cent), making their mental health worse (50 per cent) and feeling like a burden on others (23 per cent) more frequently than non-disabled people, and around twice as many disabled people (40 per cent) reported feeling lonely than non-disabled people. [16]

Negative effect on daily lives

Analysis by the Health Foundation of ONS data covering the period between 24 September and 4 October 2020 found disabled people were more likely than non-disabled people to report that COVID-19 restrictions had negatively affected their lives, with more disabled people reporting that their relationships, access to shops and access to healthcare had been affected. They were also more likely than non-disabled people to report that their medical treatment had been disrupted during the pandemic, with only 26.9 per cent of disabled people stating that their treatment had started or continued as normal compared with 44 per cent of non-disabled people. [17]

COVID-19 and older people

Older people have faced a higher risk of serious illness and death associated with COVID-19 than younger people. In May 2020, the mortality rate for those people aged over 80 years with COVID-19 was five times the average. [18]

Reduced physical activity

Analysis of the wider impacts of COVID-19 on people aged over 65 years found that between March and May 2020, almost one in three older people (32 per cent) were inactive, compared with 27 per cent in the corresponding period in 2019, and average duration of strength and balance activity decreased from 126 to 77 minutes per week. Inequalities in physical activity persisted, with those older people in the most deprived group more likely to be inactive than those in the least deprived group in both 2019 and 2020. Older people experienced a “considerable reduction in strength and balance activity between March-May 2020, with the greatest change in the age 70-74 group.” [19]

Researchers used modelling methods to predict that without mitigation, 110,000 more older people would be projected to have at least one fall per year as a result of reduced strength and balance activity during the pandemic and the total number of falls could increase by 124,000 for males (up 6.3 per cent) and 130,000 for females (up 4.4 per cent). For each year that lower levels of strength and balance activity observed during the pandemic persisted, there was projected to be an additional cost to the health and social care system resulting from the change in predicted related falls of £211 million. [20]

Impact on wellbeing

Polling carried out by Age UK into the impact of the pandemic on older people’s health and morale in October 2020 found that 34 per cent of respondents reported feeling more anxious than at the start of the pandemic. Thirty-six per cent reported feeling less motivated to do the things they enjoy and 26 per cent said they couldn’t walk as far as they used to.

In addition, 20 per cent said they were finding it harder to remember things and 18 per cent said they were less steady on their feet. [21]

COVID-19 and young people

The pandemic has also had a significant impact on the lives of children and young adults, with school closures and disrupted starts to university or working careers. Although it is difficult to establish a causal link between poor mental health in children and young people and the pandemic, government research indicates that some children and young people’s mental health and wellbeing has been “substantially impacted” during the pandemic.

A mixed picture

During the first lockdown between March and June 2020, when schools were closed to most pupils, symptoms of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) increased significantly in children aged between 7.5 and 12 years, compared with immediately before the pandemic. However, some pupils reported sleeping and feeling better and primary-aged children were more likely to report feeling happier and less lonely during the lockdown than secondary-aged children. [22]

Probable mental disorder and eating disorders

Data from February and March 2021 showed that rates of probable mental disorder increased between 2017 and 2021. In children aged 6-16 years, rates increased from 11.6 per cent to 17.4 per cent while in those aged 17-19 years, the increase was from 10.1 per cent to 17.4 per cent. The proportion of children and young people with possible eating problems also increased, from 6.7 per cent to 13 per cent for 11-16 year-olds, and from 44.6 per cent to 58.2 per cent among 17-19-year-olds. [23]

Responding to the challenges

Although the arrival of the COVID-19 vaccination programme has significantly improved outcomes for all people contracting the virus – including those with protected characteristics – inequalities persist. Health and care systems have an important role to play in mitigating these inequalities, and leaders have worked across systems to address particular issues in their local areas.

The next part of this report consists of four case studies showcasing schemes in different parts of the country targeting people with different protected characteristics.

Improving COVID-19 vaccine uptake in Norfolk and Waveney

In Norfolk and Waveney, NHS trust, CCG and public health leaders placed addressing inequalities at the centre of their system’s COVID-19 vaccination programme. Norfolk and Waveney is a large area with a higher than average rural population, with a coastal geography and areas of deprivation.

What the system faced

Vaccination levels have been high on average across the area covered by the health system, but there were some areas where uptake was still much lower than the system average. Norfolk and Waveney used a metric called the vaccine inequalities gap, which showed a range of around 20 per cent between the most- and least-vaccinated groups in the region.

What the system did

System leaders developed a vaccine inequalities oversight group whose role was to use data and business intelligence, in conjunction with local knowledge, to target work to improve uptake in these areas. Working with Norfolk and Suffolk county councils, the eight district councils and other system partners, the group put in place analytics and governance arrangements to enable a roving model of vaccine delivery.

The team deployed two vaccine buses to target specific locations and to identify underserved communities to boost vaccine uptake. The vaccine teams worked closely with local people, designated community champions and voluntary sector organisations to raise awareness of the vaccine bus visits, to improve awareness about the vaccine and to actively engage with local communities.

This activity included doorstep visits to inform residents about the buses, leaflet drops, reminder text messages and a specially designed website, built in conjunction with Norfolk County Council, to show where walk-in sites were located. Community engagement and acting on feedback informed the communications strategy and vaccination delivery approach to support equity of access and targeted approaches to underserved communities.

The team could target visits highly accurately because staff were able to use a population health management approach to identify locations with lower-than-average vaccination levels in close to real time. Working with local leaders in the eight districts across the system meant that the team could foster highly effective local relationships and achieve a greater level of understanding about specific local concerns. For instance, a vaccine bus made a night-time visit to the night-time economy and a team visited a local mosque during Ramadan to offer vaccinations to members of the local community who were fasting.

Image 1: Norfolk and Waveney’s COVID-19 vacinnation bus

Overcoming obstacles

Detecting that some local people had concerns about the vaccination programme, Norfolk and Waveney staff created a ‘worry bus’, which meant they could offer a multidisciplinary approach to supporting vaccine hesitant people to come forward, involving mental health and wellbeing team staff. This was particularly helpful in supporting people with anxiety and depression who felt uncomfortable visiting larger vaccination sites and were able to benefit from more time and space to receive their vaccination.

For people with learning disabilities and autism, a specialist vaccination clinic was established at the James Paget Hospital, to offer vaccinations in a setting where specialist clinicians were available to support service users. Vaccinations were also offered to pregnant women via maternity clinics so that staff could address specific concerns around receiving a vaccination when pregnant.

The smallest bus in the fleet of vaccine buses was the ‘SOS bus’, which was able to access smaller communities where there could be a problem using a conventional vehicle and in particular for inclusion health groups where a trusted approach was needed. This bus was able to visit homeless hostels and night shelters, Gypsy, Roma and Traveller sites and local prison estates to offer vaccinations. It was also able to provide vaccinations in places where there is a large amount of accommodation for dispersed asylum seekers. This offer adopted a making every contact count (MECC) approach which included Hepatitis C screening and social prescribing.

Image 2: Norfolk and Waveney ‘SOS bus’

Results and benefits

Although the vaccine bus initiative reached smaller numbers of people than other approaches to delivering COVID-19 vaccinations, it was able to target under-vaccinated localities highly effectively, focusing effort on some of the groups who were most vulnerable to COVID-19 infection, because of the association between higher levels of deprivation and worse COVID-19 outcomes. Staff received anecdotal reports that the scheme had also supported inclusion work by demonstrating to people in deprived communities that staff were prioritising meeting their needs.

The vaccine programme was funded using a patchwork of small funding sources including Health Equity Partnership money and Community Champions funds, as well as money specifically for vaccination of pregnant women, none of which amounted to more than £100,000 individually. This posed an additional challenge for staff who faced a larger than usual administrative burden in applying for the funding.

However, system leaders consider the initiative to have been successful and worthwhile, and an approach to addressing health inequalities. The health system is now exploring deploying the bus approach for health screening interventions and a range of other interventions in future.

Supporting teenagers’ and young adults’ mental wellbeing in Newham

A collaborative of local statutory and voluntary, community and faith sector organisations in East London created a scheme to support and develop local young adults as part of Newham's Year of the Young Person 2021/22 during the pandemic. The initiative was designed to support the mental wellbeing of young adults in Newham, a section of the community who had experienced severe restrictions on their freedom at a particularly formative time because of the pandemic.

What the system faced

Newham has a particularly high proportion of children and young people – at the time of the 2011 census, almost a quarter of residents were aged under 18 years. [24] At the start of the programme, some participants reported lacking optimism about the future, and some were experiencing issues such as poor sleep.

What the system did

Using £70,000 of funding from health and local authority partners, the collective comprising representatives from Newham Training Hub, Newham Children's Health 0-19 and HeadStart Service created Youngest In Charge, a health and wellbeing-themed programme to encourage innovation and entrepreneurship in young adults aged 16 to 25 years old.

Applicants were invited to pitch to access funds from the £70,000 pot to set up schemes to support the health and wellbeing of the wider community of young people in Newham via a participatory budgeting approach and supported through a Dragon’s Den-style nurturing and preparation process. To be eligible, projects had to be themed around tackling inequalities, improving access and uptake, and learning and development opportunities linked to health and wellbeing.

Thirteen applicants put forward proposals, with ten making it through to the final stage of the process, and nine finalists taking part in the online Dragon’s Den and final participatory budgeting process. Although the scheme was not targeted at people from specific ethnic backgrounds and it was diverse in its participants, most of the participants were from Caribbean or African backgrounds.

Each applicant was allocated a mentor to support them throughout the process, with mentors coming from Newham Health Collaborative, the GP federation and West Ham United Foundation, among other organisations. These mentors supported the applicants’ personal development as well as working with them on the projects.

Applicants made their presentations to over 125 young people, in person and online, and were able to bid for between £500 and £5,000 to fund their schemes. The bids received ranged from £750 to £5,000 in value. Just under 400 local young people scored the proposals out of ten, with three proposals becoming the eventual winners. However, because of the high-quality of the proposals, local councillors and senior management determined that all nine finalists’ schemes were funded.

Following completion of the participatory budgeting process, all the applicants were able to attend a project planning workshop to get their schemes off the ground. At this workshop, participants learned how to recruit, how to project plan and how to consider issues such as safeguarding and health and safety requirements for their schemes. Participants were able to attend workshops and undertake subsequent meetings with local community groups in person, marking a shift back towards normality following a period where face-to-face interactions had been very limited.

Results and benefits

In the end, eight projects were delivered, with 205 young people aged 14 and over from across the borough attending those eight schemes. Projects included a healthy eating scheme publicising a good diet by promoting healthy treats, a skating project and an art-based project with a focus on emotions and mental health, culminating in a borough-wide touring exhibition.

The local youth work service is now looking to work more closely with participants in the programme to deliver services within their areas of responsibility. Participants have also been able to join the local children’s health services sessional pool to access future paid work opportunities. Similarly, primary care and the GP federation are exploring how to use the scheme to improve its engagement with a segment of the population that is usually under-represented in patient involvement activities.

Building a community-led mental health recovery programme in south London

What the system faced

As the COVID-19 pandemic began in March 2020, it quickly became clear to staff working in mental health provider organisations that poorer mental health would be a lasting legacy of the health emergency.

In south London, mental health professionals were observing how fears and anxieties about COVID-19 as well as the impact of restrictions designed to slow the spread of the disease were affecting mental health and wellbeing.

What the system did

As a first response, the three mental health trusts serving the area, South London and Maudsley Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust, South West London and St George’s Mental Health NHS Trust, and Oxleas NHS Foundation Trust, set up online meetings to discuss the mental health challenges of the pandemic affecting their areas and to plan their response.

In recognition of the multi-faceted nature of the problem, local authorities and other partners including Citizens UK were invited to join an emerging taskforce chaired by former coalition health minister and chair of South London and the Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, Sir Norman Lamb, working with London Borough of Lambeth deputy leader and Mental Health Foundation president Cllr Jacqui Dyer, and London Borough of Croydon member Cllr Janet Campbell.

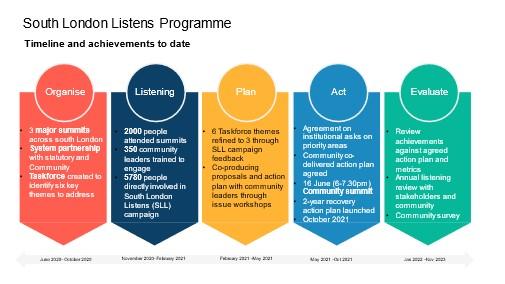

Initially called the South London Mental Ill-Health and Recovery Programme, South London Listens was set up to provide a route for listening exercises with the different communities that make up the population of south London. The programme is a partnership involving the three mental health trusts, south London local authorities, local Healthwatch organisations, south-east and south-west London integrated care systems (ICSs) and over 100 community organisations including schools, colleges, universities, faith organisations and small charities.

In November 2020, the partnership launched a four-month listening campaign, South London Listens. Communities were asked to consider six initial draft priorities, to share their views on what they felt was having the biggest impact on their mental health due to COVID-19 and to step forwards in taking an active role in shaping solutions.

Representatives were trained to listen and understand local people’s perspectives, and conversations took place with almost 6,000 people. It quickly became clear that the people whose mental health was most affected by COVID-19 tended to be from communities that were already among the most disadvantaged in the area.

Based on these conversations a series of priorities were identified around social isolation, loneliness and digital exclusion, work and wages, children, young people and parental mental health and access to mental health services. Then through workshops, a set of practical solutions were developed by community leaders and NHS and local authority partners. The action plan was launched in November and the programme has secured £1.5 million of funding to deliver projects in the plan.

Results and benefits

Although the programme has mental health and wellbeing at its heart, it is a prevention and recovery programme that looks beyond the boundaries of traditional mental health work. Elements of the plan range from placing clinicians within community organisations to train staff and provide mental health support to championing Living Wage Accreditation across the NHS and local authorities in south London.

Image 3: South London Listens' timeline and achievements

This programme sits at the heart of developments within the NHS and local authorities in south London to drive forward their roles as anchor institutions within their communities. The first action plan covers a two-year period, but the hope is that ultimately a five to ten-year plan to support south London communities will emerge from the work.

Hera Lorandos is a campaigner and fundraiser for Lewisham Refugee and Migrant Network (LRMN). Hera worked with other community representatives and trust staff to develop a plan to embed a mental health clinical adviser at LRMN under the programme.

Hera said:

“I cannot explain what a difference this will make to the people I work with. No longer will they have to face their mental health issues alone and instead will be able to get help from people they trust and understand their circumstances. And hopefully, this will mean that their stories are no longer in the shadows and we will see an end to borders in the NHS once and for all.”

Providing holistic support for people in Bradford during the pandemic

In the central Bradford area of the West Yorkshire integrated care system, a proactive care service set up shortly before the pandemic began was redesigned to provide support for people with specific needs during the COVID-19 period. The Central Locality Integrated Care Service (CLICS) comprises administrators, community connectors, advanced practitioners or physician associates and GPs. Each GP practice has a CLICS team, which is also supported by a community development worker and a volunteer coordinator working at primary care network level.

The scheme is distinctive because it offers the combined expertise of general practice and the voluntary and community sector, and enables service users to engage with team members at greater length than would be possible in a traditional GP appointment, where needed.

What the system faced

The project, which was part of the integrated care system’s Reducing Inequalities in Communities (RIC) initiative, focused on people living in Central Bradford. This area has high levels of deprivation, with a number of people who met one or more of a set of need-based criteria.

These criteria included being at greater risk of COVID-19 (having four or more clinical risk factors), having a caring responsibility, being a new asylum seeker. It was also possible for staff to refer other people into the service via a reactive pathway. The following criteria were added later:

- having received a new diagnosis of cancer or another serious long-term condition or being at the end of their life

- having recently experienced a significant health event, such as a fall or a cardiac event.

What the system did

GP practices invited patients meeting these criteria to join the CLICS. On joining the scheme, patients took part in a review and were allocated either to a community connector-led pathway, an advanced practitioner-led pathway or a jointly led pathway.

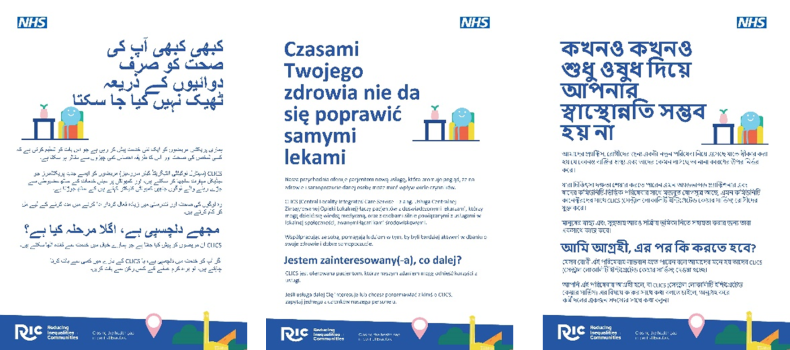

Materials about the scheme have been made available in Urdu, Hindi, Gujarati, Polish and Bengali to ensure that information would be accessible to the diverse communities that live in the area in which it operates.

Because of the risks of COVID-19 transmission, the service, which had originally been envisaged as a face-to-face social prescribing service shifted to an online approach, with online meetings and phone-call based support.

Image 4: Materials in Urdu, Polish and Bengali

Results and benefits

Under the advanced practitioner pathway, patients were able to access support such as medication reviews, assistance with referrals to other services where needed (such as mental health) and condition monitoring and lifestyle advice.

Those accessing a community connector pathway could access services such as help to get food parcels delivered from food banks, assistance with benefits, befriending schemes, housing support, health and wellbeing training and support with integrating into local community groups. For those on a combined pathway, both sets of services were available.

Dr Usman Akbar, a local GP, said:

“The Central Locality Integrated Care Service (CLICS) has had a major positive impact on our patients. It has helped to identify the right kind of support needed, particularly where this is community-based support rather than clinical.

“CLICS has helped reduce the medicalisation of non-clinical problems among our patients and we have seen a reduction in the number of patients returning to our practice for non-clinical support”.

One example of the type of support provided was that a patient who became very ill after having COVID-19 was supported by one of the scheme’s advanced practitioners while the community connector helped to deal with the social isolation they had suffered while recuperating by arranging a befriending call on a regular basis.

Overcoming obstacles

For community connectors (the scheme’s social prescribers) operating during the pandemic, not having the full range of services and community activities available for participants was a challenge, but teams linked with local community anchors so that they had a clear picture of the availability of community-based activities in each district.

Viewpoint and recommendations

The COVID-19 pandemic has had an unequal impact on people in the UK, exacerbating existing inequalities that were already being monitored using frameworks such as the Equality Act 2010’s protected characteristics.

Evidence highlighted in this report indicates that people who do not fall into the white British ethnic group, women (including pregnant women), people with disabilities and older people have all experienced worse consequences stemming from the pandemic. In some cases these relate to disease outcomes from COVID-19 itself, whereas in other cases the measures put in place to stop the spread of COVID-19, have made problems with working and living conditions worse.

As more evidence is gathered, we should be able to develop a clearer picture of the extent of COVID-19’s impact on existing inequalities and the extent to which these map onto the Equality Act’s nine protected characteristics. We will also be able to see in more detail to what extent major public health campaigns such as the national drive for COVID-19 vaccination have been able to mitigate these impacts.

In our equality, diversity and inclusion strategy, we have called for an understanding and acceptance throughout the NHS of its own agency in the creation of, and inertia in addressing, health inequalities. Recognition is needed that to deliver high-quality services for all communities, longstanding inequalities faced by the workforce and people served must be challenged and overcome. [25]

Health and care services have a major role to play in both identifying the extent of these impacts as well as working to reduce them.

This report showcases four examples of health and care systems, using innovative approaches to lessen the impact of COVID-19 on different groups of people with protected characteristics or who already experience health inequalities. For example, targeting vaccination campaigns at particular groups to boost vaccine uptake; ensuring communities have a voice in strategy development for work to improve mental health and wellbeing post-pandemic; and supporting children and young people to overcome social isolation brought about by the pandemic.

These examples demonstrate how through innovative thinking and with access to funding, health and care systems can make a difference to the most vulnerable people in their areas. But locally tailored schemes such as these can only ever be part of the picture.

The NHS and public services more broadly need to tackle the enduring effects of COVID-19 for all, preventing a further worsening of inequalities during the COVID-19 recovery. To do so, public services will need to capture high-quality data at both national and regional levels to understand who has been badly affected. Gathering this data using protected characteristics as a set of categories will not provide all the answers, but it will be a helpful place to start.

During the pandemic, barriers came down to protect staff, patients and resources, both within the NHS, and between NHS organisations and external partners in local government and the voluntary sector. The examples in this report evidence this and show that tackling health inequality in an inclusive way can be done. We must now build on this learning and these strengthened relationships to make further progress. To do so, we are encouraging health and care systems to:

- capture and analyse data on direct and indirect impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, where possible, and use the insight to plan and co-produce services wherever people with different protected characteristics experience greater adverse effects in any areas

- evaluate the impact of schemes designed by health and care systems to mitigate direct and indirect effects of the pandemic on people with different protected characteristics, where possible, so that learnings can be retained and used in future

- continue to monitor long-term effects of COVID-19 and containment measures, especially indirect effects and ensuing socio-economic impacts for people with different protected characteristics

- put processes in place to consolidate working in partnership, both within the NHS and between NHS organisations and other stakeholders, to drive continued progress in reducing inequalities affecting people with protected characteristics.

References

1. ACAS (2020) Direct and indirect discrimination: discrimination and the law, available online at: https://www.acas.org.uk/discrimination-and-the-law/direct-and-indirect-discrimination

2. Public Health England (2020) Beyond the data: understanding the impact of COVID-19 on BAME groups, available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/COVID-19-understanding-the-impact-on-bame-communities

3. Ibid

4. Women and Equalities Committee (2020) Unequal impact? Coronavirus and BAME people, available online at https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/3965/documents/39887/default/

5. Ibid

6. Ibid

7. Ibid

8. Ibid

9. Women and Equalities Committee (2021) Unequal impact? Coronavirus and the gendered economic impact, available at https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5801/cmselect/cmwomeq/385/385.pdf

10. Ibid

11. Stock, S.J. et al (2022) SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination rates in pregnant women in Scotland, Nature Medicine 28, p.504-512

13. Office for National Statistics (2021) Updated estimates of coronavirus (COVID-19) related deaths by disability status, England: 24 January to 20 November 2020, available online at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/articles/coronaviruscovid19relateddeathsbydisabilitystatusenglandandwales/24januaryto20november2020#overview-of-COVID-19-related-deaths-by-disability-status

14. Public Health England (2020) Covid 19 deaths of people identified as having learning disabilities: summary, available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/COVID-19-deaths-of-people-with-learning-disabilities/COVID-19-deaths-of-people-identified-as-having-learning-disabilities-summary

15. Office for National Statistics (2021) Coronavirus and the social impacts on disabled people in Great Britain: March 2020 to December 2021, available online at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/disability/articles/coronavirusandthesocialimpactsondisabledpeopleingreatbritain/march2020todecember2021#main-points

16. Ibid

17. Health Foundation (2021) The forgotten crisis: exploring the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on disabled people, available online at: https://www.health.org.uk/news-and-comment/blogs/the-forgotten-crisis-exploring-the-disproportionate-impact-of-the-pandemic

18. United Nations (2020) Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on older persons, available online at: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/un_policy_brief_on_covid19_and_older_persons_1_may_2020.pdf

19. Public Health England (2021) Wider impacts of COVID-19 on physical activity, deconditioning and falls in older adults, available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1010501/HEMT_Wider_Impacts_Falls.pdf

20. Ibid

21. Age UK (2020) Age UK research lays bare the drastic impact of the pandemic on our older population’s health and morale, available online at: https://www.ageuk.org.uk/latest-press/articles/2020/10/age-uk--research-into-the-effects-of-the-pandemic-on-the-older-populations-health/

22. Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (2022), 4. Children and young people, in COVID-19 mental health and wellbeing surveillance: report, available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/COVID-19-mental-health-and-wellbeing-surveillance-report/7-children-and-young-people

23. Ibid

24. Newham Info. Newham facts and figures, available online at: https://www.newham.info/

25. NHS Confederation (2021) Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Strategy