This collection focuses on the general practice component of primary care in ten year's time – a further series reflects the views of members from community pharmacy, dentistry, optometry and audiology.

We are grateful the authors – Dr Duncan Gooch, Dr Arvind Madan, Dr Dan Bunstone, Dr Joe McManners, Dr Sian Stanley and Dr Nigel Fraser – for their work and insightful contributions on the future of primary care.

The views are those of the contributing authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NHS Confederation.

Foreword

Primary care is often referred to as the backbone of the NHS – the place where patients show up and rely on those professionals to help them; the place where relationships and continuity make all the difference, the place that connects problems to solutions; the place that works within its means – and we know that high-performing primary care is key to improving health outcomes.

As we look ahead to a new ten-year plan for the NHS, this is a moment of both challenge and opportunity. The world around us is changing: patients’ needs are evolving, and their expectations are rising, while the wider economic position – much of which is beyond our control – is looming large on what we do and how we do it.

The burning platform for change is now. Lord Darzi, in his recent review, recognised that we currently spend significantly more on hospital care than on primary and community care, leading to an increasingly fragile system that fails to prioritise prevention and primary care, instead repeatedly opting to pay for the consequences of this shortfall, both financially and in terms of poorer patient outcomes. The current, highly hospital-focused, ‘sickness service’ model has become both outdated and unsustainable.

As Georg C Lichtenburg said: “I cannot say whether things will get better if we change; what I can say is they must change if they are to get better.” A resilient, sustainable healthcare system needs thriving primary care sitting within communities at the heart of delivering population-based, comprehensive, patient-centred continuity of care. So, this is a time to reimagine, to redesign and to lead.

In 2035, primary care stands at the forefront of a fundamentally reimagined healthcare landscape

This collection of essays is not a roadmap; it is a view of what the future could look like, written by those leading and working in primary care. It is intended to support both national thinking on the content of the ten-year health plan and inspire primary care leaders to recognise the opportunities that exist if they are willing to embrace them.

In 2035, primary care stands at the forefront of a fundamentally reimagined healthcare landscape – one that is personalised, proactive and deeply embedded within communities. No longer constrained by rigid structures, primary care has evolved into a system that allocates resources dynamically based on need, ensuring the right care reaches the right people at the right time. This transformation is underpinned by technology-driven personalisation, collective accountability for population health outcomes, and a health system that identifies itself around neighbourhoods rather than organisations.

We must protect what makes primary care valued – the relationships, the trust and the local knowledge. But we must also be ready to innovate, to collaborate across boundaries – health and beyond – and to embrace new ways of working that support both patients and professionals.

Ruth Rankine

Director

Primary Care Network

A vision for 2035

Dr Duncan Gooch

GP and Clinical Director, Erewash Health Partnership

Introduction

In 2035, primary care and general practice stand at the forefront of a transformed healthcare landscape – one that is personalised, proactive and deeply embedded within communities. No longer constrained by rigid structures, primary care has evolved into a system that allocates resources dynamically based on need, ensuring the right care reaches the right people at the right time. This transformation is underpinned by technology-driven personalisation, collective accountability for population health outcomes, and a workforce that values itself.

To illustrate this vision, consider Sarah, a 45-year-old woman with asthma, diabetes and work-related stress. A decade ago, Sarah’s care was fragmented, dependent on her own ability to navigate multiple appointments, with little coordination between providers. Today (2035), her care is appropriate to her needs, supported by technology-driven health planning, a proactive and risk-stratified approach to long-term conditions, and seamless integration across general practice, dentistry, optometry and community pharmacy.

Community-based healthcare: bringing care closer to home

By 2035, a fundamental shift has taken place in healthcare – care is delivered within communities rather than requiring patients to travel out of their local areas. The old paradigm of ‘out-of-community’ care being the default has been replaced by a model where people receive high-quality, personalised healthcare in the places where they live and work. The necessity of going out of the community for healthcare is now the exception, rather than the norm.

For Sarah, this means that rather than navigating multiple service providers in different locations, she receives all but the most complex care within her local area. The services required to achieve this – including diagnostics, specialist-led clinics and multidisciplinary community teams – have been developed within local hubs. Only a small number of exceptions, such as complex surgeries, highly specialised treatments, or advanced interventions requiring niche expertise, necessitate travel beyond the community.

To achieve this shift, investment in appropriate estates, workforce and resources has been a priority. Primary care at scale has been developed to provide the infrastructure and governance needed for expanded services, and healthcare professionals have been recruited and trained to deliver a wider scope of care. This has also created opportunities for better integration of social care, voluntary services and community-led health initiatives, ensuring that healthcare is not only clinically effective but also deeply rooted in the community’s broader wellbeing.

Working with local assets has been essential. Local organisations, schools, workplaces and local businesses have become active partners in delivering health interventions. From gyms offering structured health programmes to schools integrating wellbeing initiatives into their curriculum, the entire community plays a role in improving population health. This approach has also fostered trust and continuity, as patients like Sarah receive care from professionals who understand their local contexts and the factors influencing their health.

Technology-supported personalisation: from protocols to precision

The greatest shift in primary care has been the move from a generalised, protocol-driven model to a personalised, technology-enhanced approach. General practice is no longer about universal annual reviews but instead uses technology-driven risk stratification to ensure patients receive the level of care they need, when they need it most.

For Sarah, this means her digital health assistant monitors her biometric data and lifestyle habits, adjusting her care plan dynamically. If her asthma deteriorates, her GP is alerted immediately, while her community pharmacist provides targeted interventions. Meanwhile, stable aspects of her diabetes management are overseen through a digital platform, allowing her to avoid unnecessary visits while maintaining access to specialist support when needed.

The digital transformation of primary care has been made possible through sustained government investment in health technology, with national digital support and private sector partners co-developing AI-driven risk stratification tools

Crucially, relational continuity is embedded in Sarah’s care. While technology optimises efficiency, it does not replace trusted relationships with her local care team. Her general practice remains central to her neighbourhood, ensuring she continues to see familiar healthcare professionals who understand her history and preferences. These trusted relationships extend beyond clinicians to include social care, community pharmacists and voluntary organisations, reinforcing an integrated, community-based model of care. Furthermore, proactive care management teams now identify those most at risk and intervene early, reducing the need for crisis-driven care and ensuring Sarah receives the right interventions at the right time.

The digital transformation of primary care has been made possible through sustained government investment in health technology, with national digital support and private sector partners co-developing AI-driven risk stratification tools. Regulatory frameworks now mandate interoperability between GP, hospital, pharmacy and social care records, reducing inefficiencies caused by siloed data systems.

To ensure digital health solutions remain accessible, national digital inclusion policies have provided funding for community-led training programmes, ensuring patients and professionals alike can effectively use emerging technologies. Moreover, reimbursement models have adapted to support digital-first care delivery, compensating providers for proactive, technology-enabled interventions rather than just face-to-face consultations

Rethinking accountability: from individuals to population outcomes

For decades, accountability in primary care rested primarily with individual clinicians, leading to variation in practice, defensive decision-making and individualised working. By 2035, this model has shifted to collective accountability based on population health outcomes and patient experience.

Rather than being judged on how many asthma reviews they complete, local groups of practices are accountable for reducing asthma exacerbations across their local population. Similarly, dental, optometry and community pharmacy services are fully integrated into population health, ensuring that early warning signs of chronic diseases are detected and addressed collectively. Sarah benefits from this new model, as her entire care team – from her GP to her pharmacist and community optometrist – shares responsibility for improving her overall health, rather than just meeting isolated clinical targets.

Moreover, accountability structures now incentivise collaboration rather than competition, ensuring that workforce efforts are aligned towards improving outcomes rather than meeting arbitrary quotas. Groups of practices and neighbourhood collaborations work together, fostering an environment where best practices are shared, and variation is reduced, while still allowing for personalised, patient-centred care.

Additionally, primary care delivery at the neighbourhood level has fostered a distinct identity, strengthening patient trust and engagement. These neighbourhood-based collaborations ensure that healthcare is not just about delivering services but about embedding a sense of community-driven healthcare leadership, where both providers and patients are active participants in shaping health outcomes. This has led to stronger community engagement, where patients like Sarah actively contribute to shaping healthcare services through co-design initiatives and feedback loops that continuously refine and improve care models.

Workforce transformation: a profession that values itself

By 2035, the primary care workforce has undergone a major cultural shift, recognising and respecting itself as a cornerstone of the NHS. Terms and conditions are now aligned with those of secondary care, ensuring pay parity, structured career progression and protected time for professional development. This has made general practice an attractive career choice, reducing burnout and ensuring workforce sustainability.

Crucially, primary care has taken ownership of developing the workforce of the future, including clinicians and managers. Every local collaboration has embedded training and leadership programmes, ensuring the next generation of GPs, practice managers and allied health professionals are nurtured within primary care itself.

Groups of practices also function as anchors within natural communities, ensuring that healthcare is locally embedded and responsive to population need

Equally important is the full integration of dentistry, optometry and community pharmacy into the workforce model. These professions no longer operate in isolation but are recognised as fundamental to primary care’s mission. Community pharmacists, for example, are now leading routine medication reviews and chronic disease management, while optometrists provide early screening for conditions such as diabetes and stroke.

Additionally, primary care is playing a direct role in economic and workforce development. Apprenticeships, health coaching programmes and career pathways are now embedded within local healthcare collaborations, ensuring that the local workforce is trained within primary care itself. Groups of practices also function as anchors within natural communities, ensuring that healthcare is locally embedded and responsive to population needs. Harnessing community assets – including voluntary organisations, schools and local businesses – has strengthened the ecosystem of care, allowing professionals like Sarah’s GP to spend more time on meaningful patient interactions rather than administrative burdens.

Balancing prevention and productivity: a necessary tension

A major challenge in healthcare reform has always been the tension between upstream prevention and industrialised productivity. By 2035, primary care has found a way to balance these priorities by embracing hybrid models that create efficiency while preserving the human aspects of care.

The socioecological model – which emphasises addressing root causes such as housing, education and employment – has been fully integrated into primary care. Local practice collaborations work alongside local authorities and social enterprises to improve food security, air quality and physical activity, tackling the determinants of health before disease develops.

To balance this, primary care has also embraced productivity-enhancing innovations such as digital triage, remote monitoring and automation of administrative tasks. These efficiencies free up capacity, allowing GPs and other professionals to focus on complex cases and relationship-based care, rather than being overwhelmed by bureaucracy.

Furthermore, standardising algorithms and processes has been central to improving quality and reducing unnecessary variation. By adopting evidence-based digital protocols, local practice collaborations have ensured that clinical decisions are consistent, efficient and patient-centred. This standardisation has not only increased safety but also enhanced the ability to scale best practices across neighbourhoods, ensuring equitable care.

Importantly, using community assets has played a crucial role in both prevention and efficiency. By embedding dentists, optometrists and pharmacists within local health strategies, primary care has ensured that chronic diseases are identified earlier, reducing the demand on GP and hospital services. Community organisations, in turn, deliver structured health interventions that complement formal healthcare provision, ensuring that Sarah and others in her neighbourhood benefit from a holistic, responsive healthcare system.

Conclusion

By 2035, primary care has redefined itself – not just as a service but as an integrated system that personalises care, ensures accountability, values its workforce and strengthens local communities.

Sarah’s experience in 2035 is radically different from a decade ago. Her care is tailored, continuous and proactive, with technology ensuring her needs are met efficiently while still preserving the human relationships that matter most. Her health is no longer managed in isolation but as part of a broader community-wide effort, with her general practice acting as a central hub that connects healthcare, social support and economic opportunities.

The future of primary care is not just about technology or efficiency – it is about trust, collaboration and impact. By embracing this vision, we can create a primary care system that truly delivers better health for all

A seamless, smarter and sustainable NHS

Dr Arvind Madan

GP Partner, Hurley Group

Imagine a world where healthcare is not rationed by our capacity to deliver it. One where any patient query can be addressed, day or night, with such adeptness that our barriers to entry can be removed or at least lowered. Many would argue that at least a third of NHS interactions today, whether in general practice, outpatients or urgent care, were of limited value or wholly avoidable. So perhaps unlimited healthcare, in some form, is not so unimaginable if we used existing resources more wisely.

If we do it right, the NHS of 2035 will be a profoundly transformed service, built upon empowered patients, AI-enabled delivery and sustainable funding that drives a return for UK Plc. It will be designed to seamlessly integrate services across primary, community and secondary care, ensuring the right care, first time, every time. This vision outlines the key pillars underpinning a vision for the NHS in 2035.

Enhancing triage and patient flow: intelligent navigation as the default

An NHS littered with low-value interactions costs our citizens millions of avoidable journeys and billions of NHS pounds. Continuing to let patients simply guess what service they need without sufficient guidance or steer is both unsafe and unsustainable in a tight financial climate.

The single most impactful and easily implemented change we can make to patient flow is to institute a system-wide triage-led model of ‘care traffic control.’ Integrated triage systems that guide patients to the right care between connected, seamless interfaces between primary, urgent and specialist care is overdue. This will short-circuit unnecessary touchpoints in the patient journey, underpinned by advanced AI-supported triage platforms. These systems will:

- Guide patients seamlessly between self-care, primary care, diagnostics, specialist care and A&E, using channel shift between online, phone and in-person interactions, as needed.

- Use natural language processing, biometric data capture, and the patient history to auto-route cases with increasing accuracy.

- Detect and escalate red-flag symptoms, including those submitted via online interactions, wearables and home devices during out-of-hours periods.

- Directly connect patients with self-booking options as appropriate, reducing administrative bottlenecks and service workload.

- Create fluidity of case transfer with channel shift across settings and clinician types, based on each patient’s ability to engage, and their clinical need. Moving data around the system, not just people.

Beyond navigation within the primary care team, AI navigation should be extended into secondary care teams so that appropriate cases can be routed straight to diagnostics or specialist care without delay, such as breast clinics. The wiring of AI navigation tools locally should support horizontal and vertical signposting through digital integration. Additionally, richer data collection drives AI enhancements to the triage process and promotes a higher remote case closure yield by clinicians, thereby driving up their productivity. The principle should be to take a comprehensive history once and use it to get the right service first time. As triage systems mature, they will become more nuanced, for example detecting which patients would benefit from continuity with a particular clinician, rather than simply offering the first available appointment.

Currently only around 10 per cent of patient demand is coming in using online consultations. Yet we know that the more we can drive inbound demand online, the greater our opportunities to route that demand correctly and close each case with the lowest effort. Therefore, we should double down on supporting practices to adopt a total triage model of phone calls and online consults. Eventually this could include data capture from automated phone systems, which will further drive work to the right place.

Practices have historically constrained online access through capping numbers and switching off their online consultation platforms during core hours. Their contracts are top sliced to pay for access to out-of-hours services, so they understandably choose not to absorb this additional demand. Yet up to 40 per cent of patients attending A&E could have been dealt with through self-management or in primary care. While steps to cover elements of demand during core hours are being addressed in the new contract, there is a strong case for GPs being resourced to keep their online access available 24/7 to repatriate primary care suitable A&E attendances back to primary care. This will require online platforms to be able to detect serious symptoms out of hours and escalate these cases to urgent care as appropriate.

By 2035, we should target over 80 per cent of patient demand entering the NHS digitally, either through the NHS App or semi-automated phone systems, creating rich datasets that feed real-time service planning. Data from these platforms will not only power AI improvements but also drive increased rates of remote case closure, thereby freeing up clinical capacity for the minority unable to transact online. This would be a step on the road to unrationed healthcare.

Empowering patients to self-manage long-term conditions

The NHS of the future will embrace its role in enabling patient autonomy. With over 40 per cent of adults in England living with at least one long-term condition (LTC), we need to activate the digitally literate population to self-manage a greater proportion of their needs. Remote patient monitoring (RPM), through symptom and biometric tracking apps, can support this self-management and early intervention. This could be complemented with data from wearables and devices, with all this data feeding into a monitoring dashboard shared between primary and secondary care teams.

Proactive management of these LTC cohorts of patients could be delivered within the emerging service configurations, such as place or neighbourhood. These capabilities could form part of each practice’s online consultation platform, so hub-based multidisciplinary teams are managing both inbound requests for episodic issues and supporting patients proactively with their chronic conditions. From a service configuration perspective, we could combine hubs with virtual ward teams to provide 24/7 step-up and step-down wrap around care.

Earlier intervention will enhance patient empowerment, improve health outcomes, reduce A&E attendances, avoid unnecessary hospital admissions and reduce avoidable activity for the NHS

Ideally, LTC RPM should be incorporated into the NHS App. From the patient’s perspective, their personalised version of the NHS App should not just allow them to send an online consultation request but also share the care of their LTC with their clinical teams using the clinician-facing dashboard. Supporting patients to self-manage while giving them the confidence of knowing their clinical team is tracking their status represents a step-change in the NHS offer to the patients.

Through these capabilities, patients will transition from passive recipients of episodic care to active partners in the management of their health. Earlier intervention will also enhance patient empowerment, improve health outcomes, reduce A&E attendances, avoid unnecessary hospital admissions and reduce avoidable activity for the NHS.

Instead of today, where we pay for the consequences of poorly managed LTCs in more expensive hospital settings, we will offer patients the ability to have their condition continually monitored by their own clinicians, in a way that makes it easy for the clinicians to do so.

Increasing workforce productivity through technology and automation

By 2035, NHS clinicians will be supported by an AI-enabled digital co-worker. The system will no longer depend solely on increasing headcount to meet growing demand. Instead, investment in automation and intelligent tools will revolutionise primary and secondary care productivity.

Benefits of automation in general practice include all administrative tasks, such as repeat prescriptions, document coding, referral generation and results management - activities that collectively cost practices thousands of hours a year. The centre should invest in the widespread adoption of approved models using intelligent robotic process automation.

AI-driven clinical support tools using large language models will assist with case summarisation, triage and clinical decision support using the electronic health record (EHR) and national guidance. It will also generate responses to patient queries for clinicians to validate and send back. Ambient voice technology to generate medical notes and send patients a note of the consultation and self-help resources will be the norm. Some practices are already trialling AI-created avatars of their clinicians in multilingual videos encouraging patients to take up preventative services, such as immunisations.

One could argue that, as businesses, practices should be investing in many of these tools which exist now for themselves, and some are starting. However, the pace of adoption is slow, and the cost of primary care inefficiency is borne manyfold over by the wider system, so a centrally supported scale up is necessary.

Financial alignment and incentives for sustainability

GPs know how much they are funded to run their practices but have very limited understanding of what their practice costs their health system in investigations, prescriptions, referrals, A&E attendances and admissions. Commissioners have historically failed to share, incentivise or resource GPs to reduce their avoidable costs to secondary care. Clearly this broad concept needs a revised payment mechanism to gradually accelerate the left shift in resources to develop a richer range of services in the community over time, but differential investment into primary care is required to underpin the system change.

A key enabler of a future NHS is a redesigned funding model. By 2035, financial incentives must be closely aligned with system-wide outcomes. A new gain-sharing model will be necessary to incentivise primary care providers to continually expand their services from resources they release from avoidable secondary care activity.

In addition, to ensure equitable access to healthcare we should reintroduce the Deprivation Allowance (or similar equity-based model) to support practices in high-need areas. They suffer the challenges of looking after more deprived populations, struggling to hit targets, and having fewer clinicians per capita. This is asking highly mobile GPs to do a harder job with more challenged communities for less remuneration. Gaps are beginning to show.

Advancing population health management and data utilisation

The NHS of 2035 will be a data-first system, built on a foundation of advanced population health management. Predictive analytics will guide resource allocation, service design and preventative outreach programmes.

Harnessing data-driven insights can improve resource allocation and enhance health outcomes. Community-based disease management initiatives should be expanded to integrate specialist input alongside primary care teams, reducing reliance on hospitals.

Data-sharing projects, underpinned by trusted governance frameworks, should be promoted to build public trust and clinician confidence

Too many patients are denied preventative care as, due to the volume of work, their diagnosis is often not coded, so they are not included on the disease register and never receive treatment. Using AI, we can now find these codes buried in the unstructured information in the primary care EHR, identify these patients and increase the uptake of preventative management. We should drive up prevalence detection as delays cause patient harm and ultimately cost the NHS more.

The system is fearful of data-sharing and working with the academia and life sciences sectors on research. Data-sharing projects, underpinned by trusted governance frameworks, should be promoted to build public trust and clinician confidence, acting as exemplars to encourage greater cooperation across the system.

Moreover, predictive analytics for resource planning should be implemented, allowing for better anticipation of healthcare demands and preventing system bottlenecks. These strategies ensure a more efficient, data-driven approach to healthcare planning and delivery.

Primary care infrastructure fit for the future

Half of all GP practice premises are unfit for purpose. Long-term NHS transformation requires investment in modern community facilities and upgrading primary care premises.

Adopting innovative funding models such as inflation-linked leases used in Ireland’s HSE system, with integrated care boards as leaseholders, to attract private sector investment and doing away with the archaic bottleneck of District Valuer assessments could unlock our ability to fund significant numbers of state-of-the-art primary care/out-of-hospital facilities.

By co-locating health and wellness services, integrating primary care services, diagnostics, mental health services, and social care under one roof – supporting prevention, early intervention and team-based care, these premises will become the heart of the neighbourhood ecosystem. They will be the community assets through which we bring to life the health benefits of horizontal and vertical integration for a population and economic benefits for the NHS.

Conclusion

By 2035, the NHS should no longer be defined by queues, delays and inefficiencies. Instead, it will be defined by agility, intelligence and personalised care. By implementing these concrete, focused actions we can create a more efficient, patient-centred NHS without exceeding existing budgetary constraints. This transformation requires vision, investment and bold leadership. But the prize is worth it: a healthcare system that is accessible, equitable and sustainable – for patients and staff alike.

Innovating primary care

Dr Dan Bunstone

Clinical Director, Warrington Innovation Network

The opportunity for significant innovation in primary care is immense, yet we risk stifling progress by focusing too heavily on current challenges rather than future possibilities. We find ourselves in the ‘innovator’s dilemma’ – where disruptive innovation creates entirely new models, while sustaining innovation merely enhances existing models. This scenario is reminiscent of the Netflix versus Blockbuster scenario, where a revolutionary approach completely transformed an industry.

To truly revolutionise primary care, we must shift our perspective to a forward-thinking approach. This transformation involves empowering citizens, catalysing the delivery of primary care services, and realising the benefits of a system. We can create a revitalised primary care system that harnesses innovation and technology to empower patients, optimise health outcomes, and foster a thriving workforce dedicated to preventative and personalised care.

People-empowered health

The growing demand on primary care necessitates a shift from a purely clinical focus to a more holistic approach to health delivery. While social determinants play a significant role in overall health outcomes, we will concentrate on the potential impacts achievable within primary care. The core hypothesis is that a healthier population reduces demand, creating a virtuous cycle.

Empowering patients is at the heart of the transformation. Individuals are equipped with tools and knowledge to take true ownership of their health, going beyond mere control. This approach involves self-monitoring and data-driven action, supported by protocol or AI-based interactions for personalised advice. By reducing reliance on primary care services and enhancing personal accountability, patients become active participants in their health journey. For instance, if blood pressure is high, automated advice might suggest increasing physical activity, and aiming to lose 2kg, with a recommendation to recheck blood pressure in eight weeks. This low-touch approach can be applied to various health metrics, freeing up health services and improving individual health management.

Wearable technology plays a crucial role in the ten-year plan. These devices provide a rich stream of data that enables individuals to recognise signs of illness; track health improvements such as physical activity, sleep and nutrition; and make informed decisions based on real-time physiological metrics. This technology goes beyond simple step counters, incorporating clinically validated devices that offer real-time data. AI-supported systems can create bespoke treatment or lifestyle recommendations and trigger clinical escalation when necessary, opening new opportunities for illness prevention and care optimisation.

Annual clinical reviews complement the continuous data from wearables. These pre-bookable reviews support everyone and integrate wearable data. They feature near-patient testing with rapid results, contributing to a centralised ‘health metric’ visualisation. This comprehensive view provides clear, actionable next steps for clinically validated improvements. Through this approach, the focus gradually shifts from an illness service to a true health service.

The concept of citizen health scores, inspired by programmes like Vitality, further incentivises health-conscious behaviours. The system allows working-age adults to input data into the NHS App (or a proprietary app) and integrate information from wearables. By doing so, individuals can share in the financial benefits of improved health. Better health scores, reflecting reduced illness and economic costs, could lead to small but meaningful tax rebates. Additionally, healthy eating choices could be rewarded through supermarket loyalty card programmes, further encouraging positive lifestyle changes.

Primary care can evolve to empower individuals, leverage technology and create a more proactive, health-focused system. This transformation not only benefits individuals by improving their health outcomes, but also contributes to the broader economy by reducing healthcare costs and fostering a healthier, more productive population.

Catalysed health delivery

Reducing the number of people needing care is the first step in transforming healthcare delivery. The next stage involves efficiently supporting those with healthcare needs. Health delivery can be revolutionised through efficient booking mechanisms, streamlined consultations and automated administrative processes. We can enhance patient satisfaction while optimising healthcare resources.

Proactive care through data

Machine learning models will analyse anonymised patient data to predict health risks at both individual and community levels. This enables targeted preventive care, even before illness begins. GPs will have access to dashboards highlighting patients at high risk of developing specific conditions, allowing for timely interventions, and indeed predictive interventions to not only move left, but entirely shift left.

By integrating clinical data with information on social determinants of health, we can identify system and community-level health issues. The result is a more proactive and efficient healthcare system that addresses potential health issues before they become critical for the patient and costly for the system.

AI-based resource allocation

Full AI-based triage systems ensure patients are directed to the right clinicians at the right time, every time. This approach transforms demand planning into a data-driven process, making surges predictable and manageable. Healthcare teams will work differently, often in centralised hubs, and the often quoted 40 per cent of patients who don’t require primary care receiving support through alternative channels. The system will free up significant capacity overnight, addressing the recruitment crisis and reducing clinician burnout.

Patients will be able to book appointments tailored to their specific needs, with bespoke time allocations (such as ten minutes for a UTI vs 20 minutes for mental health concerns) without navigating through administrative barriers. The result is an ultra-low-friction system that benefits everyone, akin to the experience provided by companies like Amazon. The NHS App has the potential to play a crucial role in facilitating this streamlined process.

Ambient scribe

AI-powered ambient scribes will automatically transcribe and summarise consultations into a usable format, highlighting pertinent points and generating automated tasks, coding and referral letters. This technology significantly reduces administrative overhead while maintaining high-quality record-keeping. The result is more efficient consulting without compromising on the quality of patient records. The work life of all staff demonstrably improves.

Clinical decision support

At the point of care, AI will run searches through patient records to extract relevant information and results, providing real-time feedback to support high-quality decision-making. For certain conditions requiring minimal clinical intervention (such as tonsillitis with scoring criteria), the decision to prescribe can be largely automated. This approach ensures low-friction, efficient and safe healthcare delivery. Many of the large digital providers are already at this stage, with Google being a notable example.

The healthcare system can evolve to become more efficient, proactive and patient-centred. This transformation not only improves the quality of care but also optimises resource utilisation.

Unified patient records

A unified digital health record for every citizen, spanning all health and social care touchpoints, will address the complex needs of individuals and populations. This comprehensive approach allows for better stratification of populations based on need, enabling improved management and support throughout the health and wellness journey.

The lack of information visibility has been cited as a persistent obstacle across all parts of the healthcare system. By implementing a unified record system, the healthcare sector can catch up with other industries like retail, which have long since mastered information tracking. This unified system will eliminate the inefficient processing of referral and discharge letters, as patients will be fully managed at each care touchpoint. Interface issues will diminish and be addressed in real time, leading to a more seamless and efficient healthcare experience for all.

The healthcare system can evolve to become more efficient, proactive and patient-centred. This transformation not only improves the quality of care but also optimises resource utilisation.

The power of a system: a seamless continuum of care

The future of healthcare lies in the seamless integration of health and social care systems, creating a continuum where patients receive aligned support without clear demarcations between different parts of the system. This integrated approach focuses on enabling health, providing support during illness, and facilitating effective recovery. The goal is to create an environment where care is delivered holistically, regardless of which part of the system is providing it.

Nerve centres

At the heart of this integrated system are nerve centres, which provide a comprehensive view of resources across the entire healthcare ecosystem. These centres monitor hospital and community bed stock, primary and urgent care appointments, and ambulance positions and availability in real time. This approach mirrors the logistics systems used by multinational corporations like DHL, enabling a truly responsive healthcare system.

By analysing demand patterns, nerve centres can deploy teams to areas of greatest need, optimising resource allocation and improving patient outcomes. This system aims to remove the unnecessary complexity and ‘straw walls’ that currently create inefficiencies, consume time and lead to poor patient outcomes. The result is a streamlined, agile system that can respond rapidly to changing healthcare needs.

Data lakes and integrated information

The combination of health and social care data in comprehensive data lakes presents an unprecedented opportunity to impact people’s lives. By understanding the factors that contribute to illness and supporting the journey to health, we can extend not just lifespan but also health span (the period of life spent in good health). Data lakes will be structured to present information in a usable format for healthcare teams, with clear, definable outcomes. The integration of genomic data further catalyses the potential for personalised, effective interventions. This data-driven approach enables healthcare providers to tailor treatments and preventive measures to individual patients, maximising the impact of care.

Proactive interventions: shifting focus to prevention

Prevention becomes the cornerstone of the entire healthcare system in this integrated model. Recognising that preventive care is significantly more cost-effective than treating advanced illness, the system prioritises early interventions (for example, treating high blood pressure costs only pounds per patient, while managing cardiovascular events costs thousands.) In this proactive model, health and social care systems plan and work together seamlessly. The concept of ‘interfaces’ between different services disappears, replaced by a smooth flow through various care provisions. This approach ensures that patients receive the right care at the right time, often before serious health issues develop. Frictionless and effective.

By focusing on prevention and early intervention, this model has the potential to significantly improve health outcomes while optimising healthcare spending

The integration of these three elements – nerve centres, data lakes and proactive interventions – creates a healthcare system that is more efficient, effective and patient-centred. By breaking down silos between different aspects of care, this model enables:

- Better resource allocation and use across the entire healthcare system

- More accurate prediction and prevention of health issues

- Personalised care plans based on comprehensive health and social data

- Seamless transitions between different types of care as patient needs change.

This integrated approach represents a paradigm shift in healthcare delivery. It moves away from a reactive, fragmented model to a proactive, holistic system that considers all aspects of a person’s health and wellbeing. By focusing on prevention and early intervention, supported by real-time data and efficient resource management, this model has the potential to significantly improve health outcomes while optimising healthcare spending.

Conclusion

The future of primary care lies in creating a proactive, preventative and personalised healthcare system. By leveraging wearable technology, AI-driven analytics and integrated data systems, we can shift from a reactive illness service to a true health service that anticipates and prevents health issues before they arise.

This vision not only addresses the growing demand on primary care but also creates a virtuous cycle of improved health outcomes and reduced healthcare costs. By empowering patients with tools and knowledge, streamlining healthcare delivery processes and fostering collaboration between health and social care systems, we can create a more efficient, effective and patient-centred healthcare ecosystem.

The implementation will require a paradigm shift in how we approach healthcare, moving away from the traditional clinician-centric model to one that truly puts the patient at the centre of their own health. It will demand investment in technology, changes in policy, and a cultural shift in how both healthcare providers and patients engage with health management.

This approach to primary care has the potential to not only improve individual health outcomes but also to create a healthier, more resilient population. By embracing innovation and technology while maintaining a focus on human-centred care, we can build a primary care system that is fit for the future, capable of meeting the evolving health needs of our society, and extending not just our lifespan, but also our health span.

Delivering a neighbourhood health service

Dr Joe McManners

Clinical Director, OX3+ Primary Care Network

The ambition needed

The NHS has become a highly hospital-focused ‘sickness service’. For various reasons, resource and investment in primary care has dwindled as we seek to fund the consequences of our failing system. We need to build a different future, one that creates a healthier nation through a primary- and community-centred health system.

The characteristics of the new model build on the foundations of excellent primary care; population based, patient-centred, comprehensive, multi-disciplinary, with the clinician-patient relationship at its heart. As well as delivering modern, technology-enhanced personalised care, it will focus on prevention, tackling inequality and solving the root causes of ill health. It seeks to combine the best of small autonomous local teams with the benefits of larger-scale working.

If we get this right, we will see a better value and higher quality sustainable NHS. We can reverse inequalities, flip the death spiral of ever-increasing hospital resource use, improve long-term outcomes, support economic growth and enrich the lives of those living with chronic illness. Most importantly, we will see the hope of an exciting future, not only for patients, health professionals and teams, but for the health of the country.

Future model for primary care

This paradigm shift will not be realised by accident: how this happens is vital. Getting the framework, structures and policy levers right is critical to realise the vision and unlock innovation. The new model needs resource and support to be able build the structures, capability and capacity to allow the shift from the hospital to the community. We need to consider what the geography of this new environment looks like and we need to describe the financial, leadership and cultural ways that helps this change happen.

The neighbourhood health service

In this model there are two key components to delivering a neighbourhood health service.

1. Neighbourhood health network (NHN) – consisting of:

a. Expanded primary care network:

- GP practice units, including additional roles

- Primary care teams (those not part of GP teams), including community nursing

- Local social care teams.

b. Physical network of neighbourhood health centres – hub and spoke

c. Network of local council services, community and voluntary groups.

2. Neighbourhood health provider organising and supporting local network of NHNs

Neighbourhood health networks

Neighbourhood health networks (NHNs) are formal health and care networks that will enable the new community-based health model. They will bring together the health and care teams that work within natural geographies that are recognised by residents and teams that naturally would work together. They need to be large enough to have benefit of scale, but able to be sub-divided into workable operational clinical teams. They represent a coming together of public services and local communities. The NHN may well have multiple smaller neighbourhoods within it.

Being an active part of a neighbourhood health network will be an essential part of a public service contract

The NHNs are an evolution of the primary care network (PCN) model and based on similar populations. GP practices and their teams are the key building blocks, but only one part. The NHNs will include the public service teams that work most of their time in the neighbourhood, such as community nursing, health visitors, mental health workers, as well as the contracted services, such as pharmacies and opticians. They will include housing teams, local social care, public health and the voluntary sector. Being an active part of a NHN will be an essential part of a public service contract.

Neighbourhood health providers

The NHNs are supported by new NHS primary care organisations. These neighbourhood health providers (NHPs) are locality-based umbrella organisations that support a network of NHNs. They should not be too big or risk becoming overly cumbersome and institutional, but they need to be big enough to employ staff and hold contracts. They should not be part of existing large NHS organisations due to the risk of diminishing the role of primary care and being stuck in existing institutional problems. Existing collaborations and federations can evolve into these or be merged with them. The NHPs will employ staff that are not able to be employed by the organisations within them. The NHPs will also provide a potential vehicle for delivering more services out of hospital.

The leadership, constitution and governance of the NHPs will be collaborative and made up from leaders of the organisations within the NHN to build in ownership and alignment. There will need to be input and accountability to local communities and system partners.

Networks and organisations

The binding together of the neighbourhood health network is via contracts and memorandum of understanding (when a contractual route is not workable or appropriate). The neighbourhood health provider can hold contracts across larger areas and hold subcontracts as needed.

The NHNs will be given key objectives, including contractual outcomes that attract financial incentives and allow for resource to be given to teams and services that can meet the agreed objectives.

The NHN will contain ‘integrated teams’ that can deliver better and expanded complex care outside hospitals (see below). Those teams wrap around patient groups and are made up of the individuals and teams in the network, working with teams across multiple networks (for example, specialist palliative care). The teams include social workers and mental health workers, and each one is supported by a named medical specialist from the local hospital, who has dedicated time to do this.

Funding and contracts

Funding for primary care will be population based on an ‘onion’ model with three layers.

The first layer pays for GP practices. A reformed GP contract will provide a consistent core funding capitation to hold a list of patients with a named GP at its heart. The capitation will fund a minimum level of GPs/1,000 patients, prioritised towards continuity, GP-patient relationships and holistic care. The contract guarantees the increase in funding to have a minimum agreed number of GPs, but also requires it.

The next layer is extra staff and services paid for on top of GP funding, weighted to need. Staff that work in GP practices will continue to be multi-disciplinary and include nurses, care coordinators and paramedics. Funding for staff will increase and be ringfenced to ensure equitable services and proportionate to need (for example, reversing the inverse care law, levelling up not down).

The final layer of funding goes to the NHN as an extra capitation funding model tied to outcomes which are determined nationally and locally. The usage is up to the NHN.

Wrap-around funds are given to the NHN to manage and to provide an enhanced level of primary care. The fund is allocated according to population need (for example, extra funding for diabetic patients, for those over 75 years, or higher in deprived areas). The funding is to provide proactive care and support populations to prevent worsening ill health.

The overall NHN is not-for-profit, but within it individual teams can have agreed performance-related payments for keeping within budget and achieving key objectives.

Leadership

The leadership and management of these NHNs is vital. They need to have dedicated time of senior managers and clinical leaders, supported by the NHP management teams who have capability and capacity to run services and manage contracts and finances. The NHP holds a contract with the integrated care board. The NHP funding is a ‘pass through’ ringfenced fund for each NHP from the ICB, with no top slicing, but the local objectives and outcomes are agreed with and monitored by the ICB.

Infrastructure

The NHNs will work from a ‘hub and spoke’ of estates – neighbourhood health centres. They will be highly technologically powered, with very modern digital systems and equipment. Each NHN will have a ‘neighbourhood health hub’, which ideally is a large building where staff can work together, as well as a digital virtual hub. Realistically, this is likely to need to be mainly virtual until a large-scale estate plan catches up. The ‘spokes’ are key: these are physical buildings where patients can be seen and includes the network of health centres, local authority buildings and new facilities (such as ‘Health on high street’ shops and space in community centres).

Functions

The NHNs will have a number of functions:

- Integrated neighbourhood teams, whose objective is to provide proactive joined-up care for higher need groups (such as frail elderly, multi-morbidity, at-risk children, frequent attenders, serious mental health) — made up of NHN management, community health teams, specialised GPs, care coordinators, social care, hospital outreach support and more — the actual membership of the INTs is fluid and will reflect the professionals needed to manage the identified needs of patients but will have consistent leadership and coordination.

- List-based general practice, providing named GP continuity of care, especially for higher-need groups and long-term conditions.

- GPs will have dedicated list time for ‘enhanced care.’

- Same-day triaged access for urgent problems, delivered by network, includes pharmacies, opticians, dentists within the network.

- Running advanced digital systems to allow self-management and comprehensive personalised health plans.

- Preventive health programmes (such as hypertension screening).

- Intermediate health services outside hospitals, such as diagnostics and dermatology.

The changing role of the GP and team

The new model of care should be designed to ensure GPs remain in the profession and are positive and enthusiastic about the future

In the reformed system, the role of the GP is core. The new model of care should be designed to ensure GPs remain in the profession and are positive and enthusiastic about the future. This will retain, recruit and best use highly trained, experienced and trusted professionals.

Their future role includes:

- dedicated and funded leadership roles within GP partnerships, NHNs and NHPs

- portfolio work: ‘complex care’, ‘named’ GP time, specialist GP work within NHN services, as well as leadership roles and areas of interest (such aspublic health, digital)

- less bureaucracy, better digital systems and more; ‘let GPs be GPs.’

The new organisational structures mean that GPs will have options of employment by NHP or within organisations within the NHN, including partnerships in the GP surgeries. GP pay will be transparent and reflect roles and responsibilities. Negotiation with the profession is based on extra resource and reduced financial risk, in return for embracing the reforms.

GP partnerships will continue where working and will be a core part of the NHN.

To reduce financial pressure, a ‘cap and collar’ approach could be offered to result in less risk, retain a degree of financial incentives for partners within agreed parameters. This should be a win-win situation for the profession and the NHS, helping those GPs struggling with financial sustainability and removing any impression of excessive profiteering.

Rewiring primary care

Dr Sian Stanley

Clinical Director, Bishop Stortford & Valleys Primary Care Network

Primary care has recently seen a resurgence in its place within the system. The hospital-led model of care is not enough to fulfil the needs of the population, and the ageing nature of the population has created a need for holistic care, which is something that hospitals cannot do well. Primary care is poised to become everything it should always have been. We need to explore the processes and contracts that are working well and build on those, how the contract and partnership model can be used to improve pathways and promote integration, and how this integrated model could be delivered at scale.

Digital

All patient flows into primary care and the emergency department should be streamed to the appropriate healthcare provider, with concomitant patient education so they do not feel ‘short changed’ by not getting a doctor’s appointment. This digital front door should be fully interoperable with existing systems and build on the NHS App to streamline processes. Patients are the constant in their own care and should have the ability to digitally carry their own records. These systems should be safe and user friendly, ensuring secure records that travel with the patient. Any future digital commissioning should ensure that future systems interface with existing primary care systems and work across all the providers involved in that patient’s care.

We need to stop using the GP as the only trusted assessor: they may hold the record, but they should not be the only ones to act on it

Using AI, patients can be streamed to what they need rather than everything going through primary care. Care coordinators should be available to assist patients who are not digitally able to help them navigate the healthcare system. All elements of the system need to share equal responsibility for the patient journey and the concept of the GP reviewing first before other services are involved needs to be a thing of the past.

Traditionally the GP has been asked to review the patient but in the future the GP would only be involved if there was a medical need. We need to stop using the GP as the only trusted assessor: they may hold the record, but they should not be the only ones to act on it.

Alice is 96 years old. She has multiple comorbidities and is worried about a lesion on her leg. She calls the practice and is guided to an AI triage model, helped by the receptionist or the care coordinator. It is immediately noted that she has a dynamic care plan. Her issues are multifactorial, as she comments that she has in fact acquired the lesion due to a fall and this is not the first. Her son, who is usually her carer, has been unwell himself and she confides that she is worried about how they will cope this winter as there is little money coming into the household.

Her call is to the GP as she knows and understands who the GP is and what they do. The reality is that she needs a district nurse to dress her leg, a pharmacist and an occupational therapist to review her medications and see if there is anything in her home that can reduce her risk of falls. She needs a social prescriber to help understand what is going on with her son and finances, and social care to help with care, if needed.

Dynamic care planning

For all patients who are severely frail, a dynamic digital care plan should be implemented and supported, with the whole system taking an equal responsibility for their part of the care. These care plans should be updated after every hospital admission, change in medication and social care change. It should be a single record which sits at the heart of the integrated neighbourhood team and be clear, up to date and travel with the patient. It is not their entire medical record but a precis of their immediate medical and social needs, with an appropriate plan to manage their care closer to home where possible.

Reducing variation

There is a perception that if national and local commissioners centrally control how practices run this will reduce variation. It could be argued that this is part but not the whole solution. A core contract for services is required and parameters set to create a minimum viable product for all primary care. It is not possible to remove all variation across primary care due to local deviation, but there are a few core principles that should be adhered to:

- There should be a set number of appointments per thousand patients and a ratio of 20-minute complex care appointments and ten–15-minute acute appointments. How a practice decides to do this needs to be evidenced and audited based on population health management data in conjunction with the ICB teams.

- Mandate that a practice is offering the appointments that the population needs. Combining population health management data and modelling for deprivation, commissioners should work with the practices to form a structure of their appointment books. Create templates with GPs to maximise the workforce in the context of their population. The Carr Hill formula would be replaced with a formula that reflects not just allocation of funding but how that funding should be used to create the minimum viable product – this would reduce failure demand establishing local systems fit for local need.

“As a partner I can create hundreds of telephone appointments, but my population is non-English speaking and do not use the telephone – they will go to the emergency department to seek care. In theory, I have created appointments, but they are not fit for purpose.”

Using digital tools, the ICB should work with practices to ensure appropriate appointments are being offered. The Care Quality Commission should adopt failure demand as a criteria for assessing practices, auditing how many touchpoints a patient needed within the system to get the care they wanted for themselves or a relative, and the outcome of that journey.

Primary care can lean into this variability to create health settings fit for the purposes of that population, for example, in deprived areas co-locating with optometry, dentistry and community pharmacy, creating partnerships that straddle professions. People present to primary care and emergency departments because they are some of the few open access points in the system.

The partnership model should be used to its maximum potential and greater flexibility on who can become partners. For example, frailty consultants could work as partners in primary care to reduce hospital attendances; we could integrate general practice and dentistry through partnerships.

Health inequalities are the biggest variable of all, and we need to use the partnership model to create well-funded partnerships in the most deprived areas with collaborative working, shared risk, and high productivity. These should be more rewarding Alternative Provider Medical Service (APMS) contracts that have clear corporate governance structures, with partnership agreements that are standardised and overseen by regional or local bodies that have the patient and primary care at the centre of their remit. It should be mandated that a partner must work a certain number of sessions in that practice to qualify for this funding and demonstrate leadership and responsibility for the practice.

Access

Access is a perception of patients’ needs at a given time. Some patients will need more access and continuity of care and some less so, preferring a more transactional model of care. It could be argued that this is not a zero-sum game but rather a continuum, and it is often helpful for GPs to see all patients as there is always an opportunity for health education. It is clear, however, that the GP training means that we are moving more towards the model of the medical generalists. This would mean that complex care would need to be the responsibility of GPs, and working with secondary care colleagues, can put in place proactive care plans and reduce referrals.

This takes time. The traditional ten-minute appointment is not fit for this purpose and a minimum of 20 minutes would be needed. Practices need to be given autonomy to create surgeries that meet the population’s needs with minimum standards. If a practice, PCN or federation chooses to create pathways of a higher standard and that is a population need, then they should be funded for that pathway. For example, a diabetic pathway, where minimum standards are met but higher funding is available if insulin is initiated.

The future of primary care could be bright if all left-shift activity is adequately invested in – either through funding or greater sharing of workforce

Incorporated PCNs or GP federations should be able to hold contracts on behalf of smaller practices to deliver some services at scale, such as diabetes services and ADHD prescribing. This would create an intermediate tier between primary and secondary care, keeping care closer to home and reducing variability.

The future of primary care could be bright if all left-shift activity is adequately invested in – either through funding or greater sharing of workforce. It is vital to take GPs and patients on the journey too, as top-down structure and reorganisation will only stop innovation.

It is tempting to have top-down integration, with GPs monitored and micromanaged, but the vision would be to see a set of desired outcomes set nationally, a high-trust environment created and reward for excellence at a practice, PCN or alternative neighbourhood provider. This would require clear and precise contracts and collaborative agreements, with the lead provider rooted in primary care. No provider should be allowed to have an INT contract without demonstrating their ability to work with primary care and there should be clear KPIs on how this is achieved and maintained for all parties involved.

The role of primary care in at-scale provision

Dr Nigel Fraser

Chair, Taurus Healthcare GP Federation

Introduction

The government has announced its three shifts – hospital to community, analogue to digital and sickness to prevention. These are sensible and desperately needed, as it has never been clearer that we cannot just continue as we are and expect different outcomes.

We do this at a time of unprecedented financial pressures and a health service struggling to recover in the aftermath of the pandemic, albeit five years down the line. Acute hospital funding has expanded considerably over the last five years, but funding for general practice has fallen in real terms (while demand rises). Lord Darzi acknowledged in his report that despite the strategy of investing in out-of-hospital care, we have done the opposite and, unsurprisingly, are not the better for it.

There is a clear opportunity to shape thinking in this space; now is not the time to fight for the status quo

The centre will change, both in size and function; systems will be smaller and more focused on strategic commissioning; and there will be pressure for providers to look for new efficiencies. This gives a clear signal that the reform agenda has started, and a greater role will be needed from providers.

There does not appear to be a reluctance to adopt a radical approach to solving the major problems we are facing. The role of primary care in an increasingly integrated provider model is unclear and will depend on its appetite to be part of the solution. There is a clear opportunity to shape thinking in this space and now is not the time to fight for the status quo.

General practice

There is clear agreement that the foundation of general practice is the care delivered at practice level, which is indeed the ‘beating heart’ of NHS general practice and indeed the NHS. The value of continuity, for those who need it, and a longitudinal approach to care, brings the NHS immense value. This area has seen a squeeze in resources pushing practices to transform the delivery model and absorb massive real-time cuts. This has not been fair or warranted, but we may be seeing this addressed through the 2025/26 GP contract, that while not an answer, at least signals perhaps a turning point.

Primary care networks

PCNs have seen considerable investment since 2019, and with an average footprint of 30,000-50,000, allow practices to work together. While the profession remains divided on their success, there is no doubt they have provided a vehicle for GP leadership development, which is welcome. But we need to continue that journey.

GP federations and at-scale providers

Despite the role and value of federations and at-scale providers, there has been a piecemeal approach to their evolution despite them providing services that can be co-terminus with other place-based partners. There are a variety of models but where these have been successful, they have a strong governance link to membership practices and PCNs, so that the services are delivered in a truly integrated manner.

An example of this is out-of-hours provision that requires a larger footprint than PCNs and can benefit from integration with in-hours general practice. This only works when the consensus is that this is part of general practice and feels owned by general practices. This is not the case everywhere. When done successfully it can return 24/7 general practice services and enable risk and complexity to be managed out of hospital, including a more localised NHS 111 clinical assessment.

When these tiers are aligned, with the correct governance, each tier is supported by the others and general practice collectively is stronger. The other piece of the jigsaw is the vitally important role of the local medical committees that need to be involved as the statutory representatives of GPs. Getting this right is not easy and there are a variety of models where this has been enabled, such as in Cornwall; Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, Oxfordshire; and Herefordshire.

This adds enormous value to a unified voice so that general practice can be a peer at place or system level. It can provide a supportive web of services around the practice, so that the value of continuity and personal care can reach its full potential.

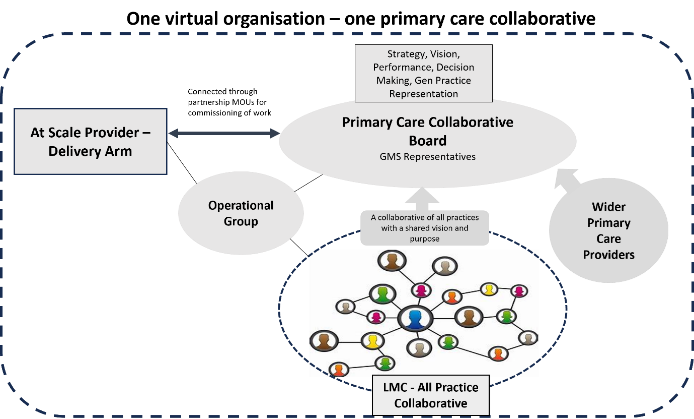

Primary care collaboratives

At-scale services could be effectively contracted through a primary care collaborative to be delivered by providers from across primary care.

Figure 1: One virtual organisation – one primary care collaborative

© Nigel Fraser

A functional primary care collaborative can provide:

- Reduced elective waiting lists.

- Improved urgent and emergency care by integrating 24/7 GP with other providers, to increase ability to hold risk out of hospital.

- Act as key integrator in neighbourhood health.

- Primary mental health care.

- Collaborative partnerships and alliance contracts with system partners primary, secondary care, VCSE, community and local authority.

- Stability to practices and a safety net for some practice risks.

- Centralised services, where it makes sense to do so, for the benefit of practices and providers, such as HR, finance, business intelligence and quality improvement.

Primary care is firmly located in the population that it serves and already demonstrates the ability to implement innovative services, efficiently and with the appropriate governance. This population-based approach aligns well with local authority partners. Likewise, when working as a collaborative, primary care is an effective peer to established NHS trusts. Many of the challenges affecting hospitals have solutions that sit or partly sit in the community, so this alignment is going to be particularly important.

Neighbourhood health

There is a government commitment to a new neighbourhood health service, and we need to make sure that at-scale general practice is ready to drive that transformation as it is well placed to be nimble and transformative.

General practice touches every part of the system and culturally understands the psychosocial factors that often are more important than those of a purely medical model. Partnerships with local authorities and VCSE are critical in building trust and engaging communities. Neighbourhood working cannot just be a diversion of the same work previously done in hospitals into the community, it must be about communities not services, and a change in mind set.

The culture is of one team wrapped around the patient, regardless of the employing organisation, and has taken strong transformational leadership from each organisation

In Herefordshire, the at-scale GP provider (owned by all the practices) provides an integrated out-of-hospital emergency care service involving acute, community and GP assets, run 24/7. The culture is of one team wrapped around the patient, regardless of the employing organisation, and has taken strong transformational leadership from each organisation. Our at-scale GP provider has a joint appointment of one of its directors as the line manager of community services, which was truly a bold step by the trust involved. It has been highly effective in reducing unnecessary bureaucracy and making sure more time is spent on direct patient care. Our community services, urgent care teams, and out-of-hours clinicians all use the GP clinical system, so the GP has complete visibility and vice versa.

Figure 2: Herefordshire Urgent Community Care Model – wrap around the patient

© Nigel Fraser

There are a variety of potential organisational forms, but it may not be useful to define these as they have evolved locally depending on local strengths. They should, however, be united in the same unified principles and values:

- Rooted in NHS values.

- Aligned around a clear social purpose, reinvesting surplus into services and having transparency of operation.

- Have primary care values: valuing practice-based working, continuity when appropriate, and appropriate governance for the service.

- Collaborative in culture.

- Should be accountable to primary care.

- Should operate on a footprint that makes sense for place-based working.

- Should be shaped by local health needs and local populations should be at the heart of decision-making.

There is of course a ‘do nothing’ approach. If we take this approach, we may lose the opportunity to lead change. Local areas will need to decide collectively how they see service provision in their own area and which model enables the best bits of primary care to be preserved and provides the appropriate level of influence.

Conclusion

Change in the health service comes in cycles and we are entering a period of reform and transformation. In general practice, this may be a once in 20- year opportunity, with a new contract and similarly the rest of the NHS moving to a new operating model. Primary care collaboratives can drive the shift to neighbourhood working and, if resourced by the wider system, can move quickly to do so. It is now the time for place-based discussions at established forums and a wider discussion in practices and with primary care colleagues. The professions need to understand the opportunities and possible outcomes as larger partners are unlikely to wait.