The preventative potential of social care

Driven largely by necessity, several NHS acute trusts have followed the lead of Sir Jim Mackey and got into the social care business. Examples of this practice range from increasing physical capacity to supporting the recruitment and retention crisis across the sector. Notable examples come from Harrogate and Liverpool.

To address persistent issues with delayed discharge of medically fit patients, Liverpool University Hospital is exploring establishing a bank of care staff, recruited on NHS terms and conditions, who would be available to fill staffing gaps in care homes. Harrogate is in the process of commissioning its own homecare services to support the three-quarters of patients caught up in delayed discharges who are eligible for homecare services.

For many years, the NHS Confederation has highlighted the dependence of the NHS on social care services and championed the need for investment in social care, particularly the recruitment and development of staff. We established the Health for Care coalition and are now working with our care colleagues to explore how that coalition can have greater influence and impact.

A different conversation

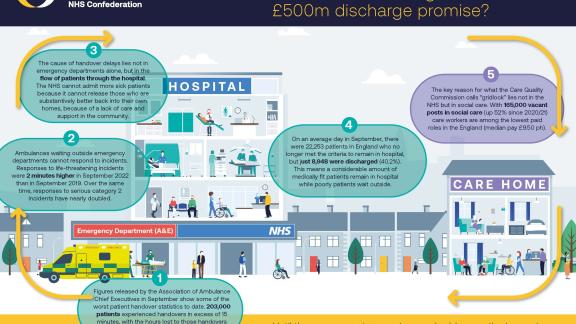

We in the NHS need to try to shift the focus of our conversation with social care colleagues. It too often seems that the only reason we engage is in seeking help getting medically fit people out of hospitals. Of course, delayed discharge is a major issue and, according to the NHS leaders I speak with, the single biggest source of capacity and flow problems in the system, in particular the urgent and emergency pathway. If health and care were completely independent of each other, we would not be required to collaborate.

The commonly imagined purpose of the social care sector as being auxiliary to the health service needs to shift

However, focusing on discharge is not a positive foundation for building these necessary relationships. On the one hand, it can too often lead to blame-mongering as each side points out what more they think the other could be doing to tackle a difficult problem. On the other, to social care colleagues, it can feel disrespectful. Social care is about a lot more than helping get old people out of hospital. Local authority social care includes services for people with mental health problems, physical and learning disabilities, substance abuse and brain injury. The commonly imagined purpose of the social care sector as being auxiliary to the health service needs to shift to reflect the independent, diverse and complex services it provides.

Reducing demand

There is, for example, the role that social care plays in prevention. The emphasis on community services in the recent urgent and emergency care (UEC) strategy is welcome and offers opportunities for stronger collaboration with social care, but the focus is still primarily on growing capacity to meet demand. Given headlines about ambulance delays and overcrowded emergency departments, this is understandable.

The welfare of patients and carers is better served by stopping people getting sick

But in the longer term we need also to focus on reducing demand through preventive measures. This is because improving prevention aligns not only with the long-term objectives of a ‘leftward shift of resources’, an objective that should be at the heart of the shift to system working, but also because the welfare of patients and carers is better served by stopping people getting sick or by helping them live good lives with sickness.

As Charlotte Augst, the former head of National Voices, has often pointed out, the relationship between sickness acuity and life quality is attenuated. People can live well with multiple and challenging conditions if they have the right support. Conversely, a single treatable illness can start a decline into multiple chronic conditions when someone is isolated and unsupported.

The problem with prevention

The scope for social care to contribute to the improvement of patient and carer welfare, and therefore reduction in demand for healthcare, seems obvious and is supported by research.

This is particularly the case if we think of social care not just in terms of services to individuals but also broader investment to grow community assets (action which will often flow through the voluntary and community sector organisations).

In a 2019 report, Skills for Care identified four dimensions of preventive social care:

- supporting people to live as healthily as possible, both mentally and physically

- reducing the use of health services, including primary care, emergency services and hospitals

- preventing or reducing the escalation of health issues

- supporting people to remain as independent as possible.

But as a report in 2021 from the Social Care Institute for Excellence recognises, there is still a lack of clarity about what we understand by prevention as well as a paucity of reliable evidence about what works. Social care is vital to the welfare and dignity of individuals and families, and a decent society should seek to provide care regardless of its consequences of other services. However, despite the launch of initiatives such as the IMPACT centre between the Health Foundation and University of Birmingham, the preventative potential of social care is undermined by this limited evidence base.

Seeing the signs

The UEC plan is welcome and necessary, but it is surely not sufficient in the long term. As one acute leader I spoke said: "If I knew who was most likely to be coming into my hospital next winter and also most likely to get stuck, I would happily spend some of my budget paying for the voluntary sector to build social support around those people… because the social signs appear before the health signs which appear before the health crisis.”

The local data is there, the forums for health, local government and other partners to collaborate have been put in place, and the need to focus more on prevention is widely accepted. We are now in position to have creative conversations with care colleagues about building fences at the top of the cliff not only whose job it is to drag people off the rocks below.

Matthew Taylor is chief executive of the NHS Confederation. You can follow Matthew on Twitter @FRSAMatthew.