Key points

- Strong collaboration between providers forms the bedrock of statutory integrated care systems. While collaboration across NHS providers has existed for many years, collaboratives have become more common in mental health through NHSE’s new care models for specialised services and in other sectors, with trusts coming together to look at streamlining resources, standardising care and offering mutual aid.

- In summer 2021, NHS England formalised the move to collaborative working and set out guidance for how providers should work together at scale in provider collaboratives. These partnership arrangements have been developing across the country, embracing the opportunity to work together at scale to tackle unwarranted variation, make improvements and deliver the best care for patients and communities.

- But since being formally mandated, how have provider collaboratives been progressing, what challenges have they faced and what opportunities lie ahead in the years to come? To discover the answers, the NHS Confederation and NHS Providers joined forces to conduct the first survey on provider collaboratives’ progress.

- This report – based on a survey of provider collaborative leaders – details what we found, including insights on provider collaboratives’ priorities and how they are building relationships with partners and integrated care boards (ICBs). It also highlights their challenges and successes, and where more support might be needed to fully realise their potential. The insights will be of interest to provider collaboratives up and down the country, to ICBs and integrated care systems (ICSs), and to policymakers looking to support their development.

- Many provider collaboratives still consider themselves in the early stages of development, with more than 70 per cent focusing on set up – such as governance arrangements, leadership models and decision-making processes – in the last 12 months. While establishment has been an important focus, a gear shift over the coming year has been signaled, with twothirds intending to focus on clinical pathway redesign or the consolidation of clinical services.

- Despite being at this early stage, collaboratives are already working to make a difference for the populations they serve: even the newer collaboratives are taking their first steps towards improving the quality of care by reducing out-of-area placements, strengthening community services, tackling backlogs and making services more efficient.

- Relationship building has been a key priority, with a positive early picture emerging of collaboratives’ engagement with ICBs, focusing on setting priorities, operational pressures and with involvement of place-based partnerships. This can be dependent on the maturity of the system and the complexity of the number of ICSs that the collaborative covers.

- Collaboratives vary by sector and in maturity. The varied nature highlights that providers are using the deliberately open statutory framework to take approaches that make sense in their local areas. Population needs, NHS priorities and local relationships will inevitably vary from ICS to ICS, but what is evident is that the permissive approach is paying off. NHS England and ministers must make efforts to preserve it.

- As well as time, collaborations need staffing, resource and leadership capacity: these are in short supply given the extreme operational and financial pressures facing the NHS at the moment. As collaboratives mature, it is vital that national leaders are realistic about the impact that external factors will have on their development. This must be reflected in national policy while pressures persist.

- The survey illustrates that trusts are committed to collaboration and realising the benefits they can bring. However, the ability to realise this potential and make a transformational contribution to care in their systems will be underpinned by access to the right support.

Introduction

Integration and collaboration are central themes of healthcare policymaking across England. Although the concept of partnership working is not new, the challenges of workforce pressures, rising demand and limited resources have increased the national focus on how organisations can work together to deliver and transform services. This has driven a clear policy move away from competition and towards collaboration. One result has been the creation of provider collaboratives. Provider collaboratives initially formed in mental health, following NHS England’s (NHSE) new care model for specialised mental health, learning disability and autism (MHLDA) services. They have more recently become common in acute settings and some community providers, with trusts coming together to look at streamlining resources, standardising care and offering mutual aid. In August 2021, NHSE formalised the move to collaborative working and set out expectations for how providers should work together in provider collaboratives through its guidance, Working Together at Scale.

The NHS Confederation and NHS Providers have taken the opportunity to evaluate the evolution of these partnerships through a joint survey. Analysis of this survey presents a view from provider collaborative leaders about how collaboratives are progressing their priorities and building relationships with partners and integrated care boards (ICBs). It also highlights their challenges and successes, and where more support might be needed.

Methodology

During a three-week period in November 2022, we invited provider collaborative leaders to respond to a survey on the development of their collaboratives. We specifically targeted those in a managing director or programme director role to understand the progress of these partnerships from an operational perspective.

We requested one response per provider collaborative. In total we received 43 responses from 42 individual provider collaboratives, giving feedback on a series of qualitative and quantitative questions. Although the exact number of provider collaboratives nationally is unknown, at the time of writing we estimate it at around 120. This means our dataset represents approximately a third of provider collaboratives in England, with an even spread of respondents from across the seven regions of the country.

Different types of provider collaboratives are at different stages of maturity. While many collaboratives of acute providers are relatively new bodies, most mental health-focused collaboratives have been in operation for several years already. To address this, we split the collaboratives that responded into four types: acute focused, mental health, learning disability and autism (MHLDA) focused, community focused, and all in (with a mixture of providers, often including the voluntary, community and social enterprise sector and/or local authorities).

We were unable to split out the results by specialised MHLDA provider collaboratives, created under the new care model, from newly forming mental health collaboratives. The chapters that follow detail what we found.

Focus and progress so far

As national policy on provider collaboratives has developed over the past year, trusts and partner organisations have started to collectively consider what their areas of focus should be. In this context, we asked respondents what the key priorities have been for their collaborative over the last 12 months (or since establishment, in the case of those that may have formed previously).

Priorities to date/over the last 12 months

- ‘Relationship building’ was the most commonly identified priority, with 86 per cent stating that this had been a key focus for their collaborative over the past 12 months

- Seven in ten respondents prioritised set up/establishment over the past 12 months

- Nearly three-quarters (74 per cent) identified ‘addressing unwarranted variations in care’ as a key priority for their collaborative.

Analysis

The strong focus on relationship building reflects the view from health leaders that collaboration between providers cannot succeed without trust and transparency. For many provider collaboratives, relationship building has been a vital part of their development, with leaders and clinical teams investing time and energy to develop mutual understanding to establish shared ambitions.

Provider collaboratives across the country vary in their maturity, with many forming in response to recent national policy directions and the experience of mutual aid during the pandemic. It is therefore unsurprising that a majority are prioritising set up and establishment. Some collaboratives have clearly been taking the time to establish themselves before embarking on transformational work to ensure that they are in the best possible position to make real change happen. Collaboratives addressing unwarranted variations in care as a key priority also reflects national guidance, which states that addressing unwarranted variation in access, experience and outcomes is a key benefit of working together at scale. [1] This corresponds with our understanding of trusts working together to improve quality of care and access by standardising service offers, pooling insights, or developing a common improvement methodology, and was chosen as a key priority across the different types of provider collaboratives.

“Raising standards of care and improving health outcomes has been a key priority over the past 12 months.” Managing director, provider collaborative focused on acute services

As well as building relationships, establishment and addressing unwarranted variation, the survey results suggest that some provider collaboratives have prioritised tackling backlogs, addressing inequalities and pathway redesign of clinical services. These areas of focus reflect the national ambitions for provider collaboratives.

“Over the past 12 months, our collaborative has been transforming services in care closer to home, prescribing and musculoskeletal services.” ‘All in’ provider collaborative

Collaboratives in different sectors appear to have different priorities: 90 per cent of acute-focused collaboratives stated that addressing care backlogs has been a key priority over the past 12 months. This is compared to 14 per cent of mental health, learning disability and autism (MHLDA) focused collaboratives. This possibly reflects the political and operational focus at a national level on elective surgery and diagnostic backlogs.

Although relationship building was seen as a priority for all sectors, respondents from MHLDA collaboratives were the least likely to identify it as a key priority. These differences may be because some mental health provider collaboratives have been established for longer; they grew from NHS England’s New Care Models programme, established in 2015, and therefore tend to have better established collaborative working arrangements.

Overall, the range of priorities outlined above suggests that provider collaboratives are making use of the flexibility afforded to them by the statutory and policy framework, and are responding to local arrangements and circumstances, and to the needs of their local populations. This permissiveness at a national level should be maintained as provider collaboratives continue to develop and start to realise the benefits of working at scale.

Benefits delivered to date

We asked respondents to outline the most material benefit their collaborative has delivered to date. The survey results produced an extensive list, suggesting that the benefits of working together at scale are starting to be realised. For example:

“[Working collaboratively has] improved patient outcomes through reduction in out-of-area placements and reduced waiting times and lists.” Managing director, provider collaborative focused on mental health, learning disabilities and autism services

“[Collaborative working has] provided an opportunity for long wait patients to access quicker diagnostic and elective procedures by working as a set of acute providers rather than individually.” Programme director, provider collaborative focused on acute and acute specialist services

“[Our collaborative has been able to] invest savings in strengthened community services that provide greater choice for patients and improved experience.” Managing director, provider collaborative focused on mental health, learning disabilities and autism services

Analysis

Reducing out-of-area placements and length of stay were some of the most common benefits identified within the survey – this is driven by respondents from MHLDA-focused collaboratives, which are working to enable patients to be treated closer to home and for a shorter period of time. This reflects what we have been hearing from collaboratives such as South London Mental Health and Community Partnership, whose members worked together to develop a new pathway for forensic care, including all medium secure, low secure and community outreach services across south London.

Elective recovery and mutual aid were also cited by several respondents as a material benefit they have delivered to date.

Spotlight

The Black Country Provider Collaborative has acted collectively to tackle long waits for breast cancer services. This type of collective working has enabled patients to access services quicker than they would have if trusts were working individually.

Respondents also cited efficiency savings as a material benefit, for example reducing costs through joint procurement, which has freed up funding to reinvest in frontline services.

The number of reported benefits supports evidence that there are already many examples of good practice emerging across the country. The range of benefits reflects the diversity of ambitions provider collaboratives have to improve services for their populations and demonstrates the value of the permissive approach being taken nationally.

Improvement approach

The challenging operational context underlines the importance of quality improvement – the systematic application of tools and approaches to improve care quality, productivity and outcomes for patients. Organisations around the country are exploring how to sustainably implement quality improvement approaches and are investing in improvement capabilities and skills. National policy has highlighted opportunities for provider collaboratives to play a part in supporting improvement through deploying joint quality improvement frameworks. [2] We asked respondents to describe the extent of their collaborative’s focus on quality improvement.

Focus on quality improvement

- More than nine in ten respondents indicated their collaborative was developing work focused on embedding improvement.

- Just over half (51 per cent) said they have developed and are ‘actively applying’ a common approach to improvement through their collaborative.

- Around a fifth of responses (18 per cent) indicated their member trust has committed to a joint programme of work around improvement but is yet to begin development work to shape and implement it.

Analysis

Responses suggest many collaborative leaders agree that there is an opportunity to add value around quality improvement and, as such, are making quality improvement a strategic focus for their collaborative.

However, survey responses also suggest real variation in the extent to which collaboratives have made progress. Just over half indicated they have developed and are ‘actively applying’ a common approach to improvement through their collaborative. Most of the other respondents indicated that their joint work around improvement is at an earlier stage of development.

Approaches to quality improvement

Quality improvement is a diverse category of approaches with a range of theories, tools and methodologies used in many health and care systems internationally. [3] We asked collaborative leaders to provide some headline details about how their collaborative is seeking to embed improvement approaches and disciplines.

- Over half of respondents (54 per cent) indicated their collaborative is developing a ‘shared vision and shared principle’ to inform members’ improvement work.

- Just under half said their collaborative was supporting ‘networks for shared learning and improvement in place’ (49 per cent), or said they had ‘agreed behaviours between partners’ (46 per cent).

- Only around a third (36 per cent) said their collaborative was developing a ‘common methodology’ for improvement work.

Analysis

Embedding systematic quality improvement work is a real focus for many provider collaborative leaders, and a range of activity is underway today. The approach and role that collaboratives will play in driving quality improvement at scale will vary around the country. In many cases, trusts or other organisations within collaboratives will lead improvement work locally, with their collaborative(s) operating in supportive or enabling roles, including flexibly contributing improvement capabilities and resources. Some collaboratives will also play a role in joining up operational teams to share learning and approaches.

Only a minority of respondents suggested their collaborative intends to embed a common improvement methodology across its members.

It is worth noting that some collaboratives are only beginning to embed their improvement work, with a small number indicating it is ‘too early’ to describe their collaborative’s role in this area

How are provider collaboratives set up

Governance model

There is flexibility in the national policy framework for trusts to develop collaborative arrangements that make sense in their local context and may be shaped by the shared priorities trust leaders identify. As a result, collaboratives vary in the form they take. National guidance highlights three main governance models for collaboratives: [4]

| Provider leadership board | Lead provider | Shared leadership |

|---|---|---|

| Senior leaders from participating trusts establishing a joint forum to shape a collaborative agenda. The joint forum may operate with delegated authority to take decisions for the member trusts. | A single trust holding a contract with a commissioner and sub-contracting with other trusts in the collaborative to coordinate service delivery and improvement. In some cases, a lead provider may use its existing governance arrangements to support decision-making within a collaborative. | Multiple trusts appointing a single person (or group of people) to fulfil key leadership roles across the collaborative – particularly the chief executive role – while maintaining specific leadership capabilities for each member trust within the group |

We asked respondents which of the governance models best describe the approach their provider collaborative is taking. The provider leadership board model was the most common governance approach, with 40 per cent of respondents reporting that they are using this model. 29 per cent said they would use the lead provider option, while 17 per cent said they were opting for the shared leadership model. 14 per cent said they use something else or are still deciding on the model they plan to use.

Analysis

The spread of models being used shows trusts are making use of the flexibilities available to them as they establish their collaboratives.

The lead provider model has been very popular with MHLDA-focused collaboratives: all of the 12 respondents that reported using the lead provider approach come from that sector. Lead provider arrangements have been widely used by mental health collaboratives [5] that have taken on specialised commissioning delegated budgets and functions from NHS in recent years. This may in part also reflect the fact that mental health collaboratives are potentially more likely to involve a mix of provider types, including trusts, the voluntary sector and independent sector partners.

For ‘all in’ and acute-focused provider collaboratives, the provider leadership model with a committee in common approach is often employed, with all of the ‘all in’ provider collaboratives that responded reporting using this model. In the acute sector the most commonly used approach was the provider leadership model (five out of ten).

Dedicated delivery resource for collaboratives

There is no additional funding from national bodies to set up and run provider collaboratives, so trusts have drawn on existing budgets, clinical staff and leadership teams to resource their establishment and programmes. In some instances, this has been resourced by trusts sharing the costs of a programme manager or director role – sometimes these roles are staffed by trust employees on secondment.

- Almost all respondents (98 per cent) said their provider collaborative has some form of funded and dedicated resource.

- Only one respondent said they have no dedicated and funded resource. However, this collaborative reported being at the beginning of the collaboration process.

- The survey showed that 42 per cent have dedicated funding for a managing director and 60 per cent have a funded programme director.

- Half of the provider collaboratives have a funded clinical director role; just under half (47 per cent) have project management office (PMO) support.

Analysis

The scale of programme management function can depend on the ambitions of the collaborative, with some using only a small number of staff and others creating substantial teams. Other funded roles within provider collaboratives included commissioning and contracting leads, which featured in 31 per cent of responses. These roles were only found in mental health and learning disability and autism (MHLDA) focused provider collaboratives, the majority of which were using the lead provider model to take on delegations from NHS England’s specialised commissioning.

Whole-time equivalent roles

Although almost all respondents had at least one funded role, there was a broad range in the number of whole-time equivalent (WTE) funded roles in a provider collaborative:

- only one provider collaborative had no WTE roles

- the collaborative with the most funded roles had 27 WTE posts

- the median figure was four WTE roles.

Analysis

Our survey showed that 43 per cent of respondents had fewer than five WTE funded roles in their provider collaborative. A further 19 per cent had between five and ten WTE funded roles. Of those provider collaboratives that have more than ten WTE-funded roles, all were from well-established provider collaboratives.

From this survey we are unable to say whether there is a link between the number of funded WTE roles in a provider collaborative and the impact a collaborative is making. However, it is likely that as a provider collaborative becomes more established and takes on more responsibility for the delivery and commissioning of services across a system, the more dedicated resource is required.

Relationships with partners

We asked provider collaborative leaders about how well their collaborative is engaging with other partners within the system. Positive relationships are considered one of the key enablers of effective provider collaboratives, with NHS England guidance stating that ‘building and nurturing strong relationships among trust leaders, clinical teams and with system partners at all levels, based on honesty and transparency, is critical.’[6]

Although we did not focus primarily on relationships within the provider collaborative, when asked about challenges to embedding the provider collaborative, immature relationships between providers were not viewed as a huge issue as only 10 per cent saw it as a significant challenge, and almost three-quarters of respondents (72 per cent) stated that it was only a slight challenge or no challenge at all.

In terms of external relationships, the results present a positive early picture of collaboratives’ engagement with ICBs, focusing on setting priorities, operational pressures and with involvement of place-based partnerships. Relationships with voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) sector partners and primary care networks (PCNs) are for many still in their infancy, though we expect these to strengthen over time.

Although we did not focus primarily on relationships within the provider collaborative, when asked about challenges to embedding the provider collaborative, immature relationships between providers were not viewed as a huge issue as only 10 per cent saw it as a significant challenge, and almost three-quarters of respondents (72 per cent) stated that it was only a slight challenge or no challenge at all.

In terms of external relationships, the results present a positive early picture of collaboratives’ engagement with ICBs, focusing on setting priorities, operational pressures and with involvement of place-based partnerships. Relationships with voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) sector partners and primary care networks (PCNs) are for many still in their infancy, though we expect these to strengthen over time.

Relationships with ICBs

- Nearly seven in ten (68 per cent) stated that they strongly agreed or agreed with the statement that ‘the collaborative and ICB(s) are working well together to plan and set priorities’. A quarter (24 per cent) were neutral and only 2 (5 per cent) disagreed.

- Just over half (57 per cent) stated that they strongly agreed or agreed that ‘the collaborative and ICB(s) are working well together to address operational pressures’. Two in five (38 per cent) were neutral.

- A quarter (24 per cent) strongly agreed or agreed that ‘the collaborative and ICB(s) are working well together to monitor service performance.’ Only a small minority (16 per cent) strongly disagreed or disagreed, while over half (57 per cent) were neutral.

Analysis

Our survey indicates early signs that positive relationships are being established between provider collaboratives and ICBs on planning and setting priorities together. The results align with the conversations that both the NHS Confederation and NHS Providers have had with collaborative leaders over recent months, in which several leaders have welcomed the nature of the relationship with their ICB(s) so far as being equal and co-operative, rather than top-down and directive.

While frequency of collaboratives’ engagement with their ICB(s) was not covered in the survey questions, it is worth noting that this is likely to vary depending on factors such as the maturity of the ICB and the scope of different types of collaboratives. We know, for example, that most acute collaboratives are prioritising the recovery of care backlogs (see section on ‘Priorities to date/over the last 12 months’), which is likely to involve regular engagement with the ICB given the current national focus in this area. Other collaboratives, such as those focused on specialised commissioning in mental health, are likely to have less frequent engagement with their ICB(s), due to their specialist nature, or the fact that some of the MHLDA collaboratives span a number of ICB areas:

“Because of the specialist nature of our collaborative we have fairly infrequent interactions with the ICB from a collaborative perspective.” Programme manager, provider collaborative focused on adult secure services

“We work with five ICBs… Each ICB is at a different level of maturity which impacts on progress to re-design end to end pathways.” Managing director, MHLDA provider collaborative

On addressing operational pressures, our survey paints a picture of broadly positive working between collaboratives and ICBs. That said, a high number of respondents answered ‘neutral’ and the reasons behind this require further investigation. For some, it may simply be that addressing operational pressures sits outside of the current scope of the collaborative. Yet even for the acute collaboratives focused on recovery of care (see section on ‘Priorities to date/over the last 12 months’), nearly two-thirds (60 per cent) answered neutral. The comments received indicate that this could be due to relationships, ways of working and governance arrangements still taking shape:

“[We] need to develop mutual confidence and trust in respective roles.” Programme director, acute-focused provider collaborative

“[We are] currently developing / agreeing governance proposals that move us from the transitional 22/23 arrangements to a more formalised agreement for 23/24.” Programme director, acute-focused provider collaborative

On working with ICBs to monitor service performance, there was more variation. A high number of ‘neutral’ responses suggests that at this early stage of collaboratives’ journey few are taking on this function. One respondent commented:

“There is no expectation of a role in operational or performance at present.” Director of strategy

Maturity again may be a key factor here. We know many of the collaboratives that responded are still relatively new. As alluded to, however, some ICBs are relatively immature as statutory bodies, having only been set up in July 2022. This was given as a reason for answering neutral by the following respondent:

“To be fair, I think the ICB is still in the midst of figuring out its role in the system, so it’s taking a little longer right now than it will in future.” Managing director, all-in provider collaborative

Another explanation, however, is that for many, monitoring service performance is itself a contentious aspect of provider collaboratives and system working more broadly. Through conversations with provider collaborative leaders, there is the view that they do not wish to see collaboratives become performance managers. Instead, they would like trusts and collaboratives to be more focused on joint working, peer support and coordination.

“Performance management space is challenging. Our collaborative is very clear in its focus - peer support, not performance management.” Managing director, acute provider collaborative

Relationships with other system partners

- Seven out of ten (68 per cent) respondents indicated that their provider collaborative was meeting with place-based partnership(s) very regularly (at least once a month) or quite regularly (at least once every three months).

- Almost six out of ten (58 per cent) indicated that their collaborative was meeting with local authorities very or quite regularly.

- Just over half (56 per cent) indicated that their collaborative was meeting with voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) sector organisations very or quite regularly. However, one in ten (9.8 per cent) said they had not yet met with the VCSE sector.

- The lowest frequency of engagement was with PCNs. Only one-third of respondents (30 per cent) said they were meeting with PCNs very or quite regularly. And, seven in ten (70 per cent) said they rarely or never meet with PCNs

Analysis

Provider collaboratives form one part of the complex delivery and partnership working arrangements within ICSs. Close relationships and regular engagement will be key to managing this complexity and delivering programmes of work that span across partnership vehicles. For example, work to improve discharge and community support for patients leaving hospital may require joint involvement across collaboratives and place partnerships.

Our survey shows that provider collaboratives already appear to be engaging closely with place-based partnerships. The NHS Confederation and NHS Providers are clear that both can be complementary drivers of integration within systems. They will be key to the delivery and improvement of services for patients. However, this is dependent on clear understanding within the system of respective priorities, functions and accountabilities. It is therefore positive that there already appears to be regular interaction between the two, even with both in their infancy in many parts of the country.

Engagement with PCNs, and to a lesser extent the VCSE sector, appears less frequent. This is particularly so among acute-focused collaboratives: none of the leaders of these collaboratives said that they met with PCNs very regularly, with four in five (78 per cent) saying they met with PCNs very rarely or never.

This is understandable given the early stage many collaboratives are currently at, particular those primarily made up of acute trusts, though there are other reasons why engagement with PCNs and VCSE may be less frequent than with ICBs and place-based partnerships:

- Some provider collaborative leaders have indicated that part of the challenge of engaging with both has been the number of PCNs and VCSE organisations across their system, often with a lack of an authoritative ‘single voice’ for the sector.

- Relationships with PCNs and VCSE organisations may in some parts of the country sit more naturally with individual members of the collaborative or at place, as opposed with the collaborative itself. For example, a district general hospital in a rural county seeking to improve pathways or access with PCNs may have direct contact with them as a trust rather than through the collaborative.

- PCNs and VCSE organisations are represented within many place-based partnerships. This means that for provider collaboratives that are engaging regularly with partners at place, additional direct engagement is unnecessary.

- The level of engagement with different system partners will depend on the priorities and strategic objectives of individual collaboratives. We have spoken to acute-focused collaboratives, for example, who at present are focused on issues such as governance, procurement and workforce, none of which require the input of wider stakeholders.

It should be noted that some provider collaborative leaders have indicated the level of engagement with PCNs and VCSE organisations is likely to increase over the coming year as provider collaboratives begin to focus on clinical pathway redesign and consolidation of services (see section on priorities and challenges).

Priorities and challenges

We asked provider collaborative leaders about what issues they will be prioritising over the coming year, as well as what they anticipate their key challenges will be.

The results show a desire among collaboratives to begin improving clinical pathways and addressing variations in care. There is a desire among some collaboratives to take on delegated functions from the ICB in 2023/24 or 2024/25, but not a majority. Looking ahead, workforce pressures are identified as the top challenges for collaboratives.

Priorities

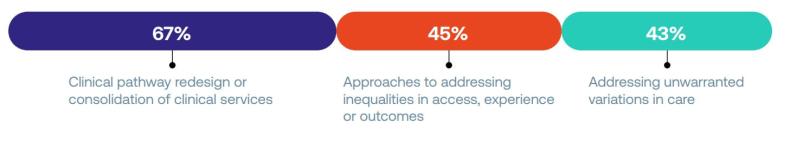

When asked about what they expect to be the collaborative’s top three priorities over the coming 12 months, two-thirds said ‘clinical pathway redesign or consolidation of clinical services’ (67 per cent). The next most popular answers, given by over two in five, were ‘approaches to addressing inequalities in access, experience or outcomes’ (45 per cent) and ‘addressing unwarranted variations in care’ (43 per cent).

Figure 8: What do you expect to be your collaborative’s top three priorities over the coming 12 months?

There was evidence of provider collaboratives making progress in many of these areas.

Spotlight

The West Yorkshire Association of Acute Trusts (WYAAT), which has been in operation as an acute collaborative for a number of years, has introduced an overarching single, shared regional vascular service to ensure that patients, regardless of where they live within West Yorkshire, have access to the same high-quality treatment.

Analysis

It is unsurprising that clinical pathway redesign and consolidation of services is seen as a priority for provider collaboratives over the next 12 months. We know from conversations with provider collaborative leaders that many feel this is where collaborative working can be of most value to patients.

Though some collaboratives are in certain respects starting from scratch, in many parts of the country there are established clinical networks (established by NHS England in 2013 to develop a system wide approach to service improvement) which provide an important platform for collaboratives to make progress in redesigning services. In Cheshire and Merseyside, the cancer alliance worked with the emerging provider collaborative to develop a regional cancer surgical hub, which coordinates mutual aid between providers to ensure that patients are prioritised and not disadvantaged by any local capacity constraints.[7]

Provider collaborative leaders across the country see the relationship with clinical networks as a key one for improving pathway design and quality. Many want to work closely with the clinical networks in their area, with some expressing a desire to oversee networks on behalf of the ICB.

Among acute-focused collaborative leaders specifically, recovery of care backlogs was given as a top three priority for the coming 12 months by one in two (50 per cent). Many of the ICS leaders engaged through the NHS Confederation’s ICS Network have indicated that they see provider collaboratives as a key body through which to accelerate progress on their backlog of patients awaiting elective care.

In contrast to the earlier question about collaboratives’ focus to date, ‘relationship building’ was identified as a future priority by relatively few respondents. Collaboratives may anticipate their foundational relationship building has been completed, however many collaborative leaders have shared their concern that trust between partners takes time to build but can be quickly lost. We would therefore anticipate processes around maintaining relationships and organisation development to continue to be at the forefront of leaders’ minds as collaboratives take on responsibility for delivering system ambitions.

Delegated responsibilities from ICBs

- Sixteen (40 per cent) respondents are currently considering using legal flexibilities created through the Health and Social Care Act 2022 to take on delegations or jointly exercise statutory functions in 2023/24 or 2024/25. However, 20 (50 per cent) said it was too early to say and four (10 per cent) said this was something they were not considering.

- When asked about barriers to delegation, four answers were most prominent. Almost half (47 per cent) said workforce/ resourcing the collaborative, while just over two in five said ICB hesitance to delegate (45 per cent), funding (45 per cent) and immature relationship between the collaborative and ICB (42 per cent).

Analysis

Sections 65Z5 and 65Z6 of the Health and Social Care Act 2022 allow ICBs, trusts and foundation trusts to delegate their functions to each other, jointly exercise functions and form joint committees. However, NHS England has recommended that ICBs do not delegate functions to providers in 2022/23.

Our results reveal a relatively high number of collaborative leaders wishing to take on delegated functions in 2023/34 or 2024/25. However, we suspect only a minority of collaboratives are likely to take on delegations in the next two financial years given the level of trust, maturity and resource that will be required to do so.

“We want delegation to be used as a lever, not an end point, so we may have to consider delegation if necessary but we aren’t focusing on that as a goal specifically.” Managing director, all-in provider collaborative

It is worth noting that delegation should not necessarily be something for collaboratives and ICBs to aim for. It is a legal mechanism that may work for some collaboratives but would not work for all, with skepticism being expressed by many collaborative leaders on whether delegation(s) will help them progress their objectives and priorities. For half of our respondents, it is too early to say if that is an avenue they want to explore. One in ten are not considering delegation at all.

This is important context for understanding how collaboratives will develop and the support they will require, which will need to span both delegated and non-delegated models. This should be noted by NHS England as they develop guidance on delegation to provider collaboratives, which we believe should make clear that delegation is a means to an end rather than an end in itself. In the words of one respondent:

“We are a longstanding collaborative and at no point has a lack of delegation of responsibilities hindered our progress on collaborative aims. Delegation can require significant administrative effort and additional governance processes, which may detract from the real transformational work to deliver sustainable services and high-quality outcomes to patients.” Managing director, acute-focused collaborative

“Formal delegation needs to be an option to achieve an objective, not an end in itself. This is not to rule delegation out entirely but there is currently no imperative to pursue this as we have, and continue to make, improvements to services without the necessity to use such approaches.” Managing director, acute-focused provider collaborative

The answers given on delegation varied based on the focus and scope of different types of collaborative. For example, three in five (60 per cent) acute-focused collaboratives answered that they were considering delegation in 2023/24 or 2024/25, compared to two in five (39 per cent) mental health focused collaboratives and one in five (20 per cent) community-focused collaboratives. Further research is needed to explore the reasons behind this, though it may be that respondents from acute-focused collaboratives felt that their priorities (such as recovery of elective backlogs) could be better achieved through delegation, or that formal delegation is at the insistence of the ICB in certain areas of service delivery.

In terms of barriers, workforce/resourcing has come up frequently in our engagement with provider collaborative leaders. Many we have spoken to believe that if the ICB is to delegate functions to collaboratives then the resource ‘should follow’. Some have outlined tensions in this regard, with collaborative leaders having to be clear about the limits of what they can take on without funding for more resource. Concerns around workforce are explored further in the following section on wider challenges.

Again, the barriers listed above should form the list of areas to explore further in a support offer focused on collaboratives developing delegated models of operating.

Wider challenges

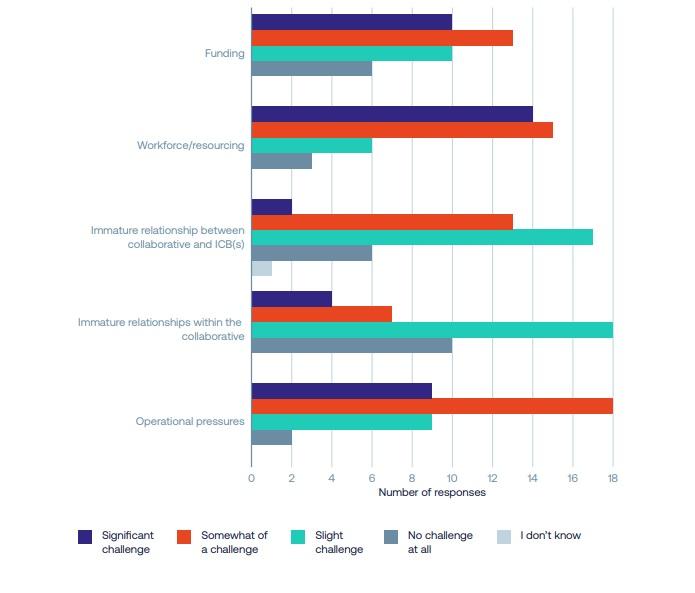

Although there have been several material benefits identified and realised by provider collaboratives in their formative year/s, it is clear that challenges remain when exploring the opportunities of collaboration at scale. We asked respondents to indicate the significance of a selection of challenges to embedding and developing their provider collaborative so far.

- Workforce and resourcing were seen as a ‘significant challenge’ or ‘somewhat of a challenge’ by over three-quarters of the respondents (76 per cent). Only one in ten (8 per cent) saw it as no challenge at all.

- Operational pressures were also of high concern to provider collaborative leaders, with 71 per cent stating that this was a ‘significant challenge’ or ‘somewhat of a challenge’.

- Funding was considered a ‘significant challenge’ or ‘somewhat of a challenge’ by three in five (59 per cent).

Figure 10: The significance of the following challenges to embedding and developing provider collaboratives so far

Analysis

We have heard from some provider collaborative leaders that workforce and resourcing have been a key issue due to lack of staff to fill roles and problems around retention. This was reflected in comments such as:

“Workforce is one of the main challenges we face – the sheer number of staff leaving the NHS is the biggest challenge.” Programme director, mental health and learning disabilities provider collaborative

Based on conversations with provider collaborative leaders, we understand this as a shared workforce problem for the trusts within collaboratives, with over 130,000 vacancies across the NHS. As highlighted in the section on dedicated delivery resource for collaboratives, there is also a challenge in some collaboratives around the need for appropriate resource to support the running of the collaborative. This appears to be focused more on funding or capacity to create these roles as opposed to provider collaboratives not being able to fill dedicated roles for the collaborative specifically.

Despite the workforce challenges across collaboratives, our survey also showed that less than two in five (16.7 per cent) intend to prioritise ‘changing recruitment and retention practices and/or broader workforce development’ over the coming 12 months. While we know that some are undertaking or planning work in this area, it may be that many collaboratives consider this to be an issue best solved at system and/or individual trust level.

On funding, some provider collaboratives are managing despite constrained finances. However, a key issue is that providers within systems often have very different financial outlooks.

“Funding is a very big challenge as there is an agreement across the three trusts that two of the trusts have been under-funded for some time. The biggest challenge we will face is how to divide the funding appropriately moving forward.” Programme manager, community collaborative

Under the Health and Social Care Act 2022, ICBs have a duty to ensure their annual budgets are not exceeded and this is likely to be a key focus for ICB leaders in their engagement with provider collaboratives over the coming years. The HSJ reported two in three ICSs have already reported deficits against their year-to-date financial plans for 2022/23.

The results relating to funding, workforce and operational pressures point to the cross-cutting issues health leaders face as they struggle with limited capacity, both in terms of staff and funding, and increasing demand for care from their populations. These pressures can make it difficult for organisations or leaders to devote time or resource to collaborative ambitions such as service transformation programmes.

Overall, it is clear to see that the impact of constrained resource at a time of extraordinary demand is posing a challenge to the development of provider collaboratives: national bodies must acknowledge that capacity and time are needed for leaders and organisations to ensure the delivery of a collaborative’s work programme.

Viewpoint

Although collaboration between providers is not new, with some collaboratives being well-established already, our survey suggests that many provider collaboratives could still consider themselves as being in the early stages of development. Given the relative infancy of many of these collaboratives, and given that statutory ICSs are still less than one year old, it is unsurprising that a number have chosen to focus on foundational work over the past 12 months. This includes putting in place governance arrangements, selecting appropriate leadership models and developing decision-making processes.

Collaboratives have also dedicated time to forming and cementing relationships between their partnership organisations, as well as with wider system components such as ICBs and place-based partnerships. All these activities are essential elements for a provider collaborative to be effective and have therefore been a key priority for a lot of the collaboratives.

Despite being at this early stage, it is encouraging to see that collaboratives are already working to make a difference for the populations they serve: even the newer collaboratives are taking their first steps towards improving the quality of care, reducing backlogs and making services more efficient. These findings give the first indications of where providers believe they make services better through joint working. The findings also show that providers are seizing the opportunity to act together to improve care, and give real cause for optimism about the contribution they will make in the years ahead.

As well as reflecting the priorities of different provider collaboratives and the benefits they are already achieving, our survey results also demonstrates that collaboratives vary by sector. Those focused on MHLDA tend to be more mature and consequently less focused on set up. Because the first MHLDA-focused collaboratives were set up primarily to take responsibility from NHSE to commission specialised services, they are more likely than other collaboratives to use the lead provider model. And because the operational issues facing MHLDA services are different to those in the acute sector, MHLDA collaboratives are less likely to be working on care backlogs. Instead, they are often focused on cutting lengths of stay for inpatients and reducing the rates of out-of-area placements.

This diversity in approaches is just one way in which providers are using the deliberately open statutory framework to take approaches that make sense in their local areas. Population needs, NHS priorities and local relationships will inevitably vary from ICS to ICS. It is welcome, appropriate and desirable that collaboratives’ initial priorities, ways of working and composition reflect local needs. The permissive approach is paying off and NHSE and ministers must preserve it.

It must be borne in mind that the best-established provider collaboratives are already several years old, while others have only begun to form over the past year. Joint working can take years to bear fruit, and many respondents to our survey are only beginning to build their collaborations. As well as time, collaborations also need staffing, resource and leadership capacity: these are in short supply given the extreme operational and financial pressures facing the NHS at the moment. As collaboratives mature, it is vital that national leaders are realistic about the impact that external factors will have on their development. This must be reflected in national policy while pressures persist.

There was a clear theme in the responses to our survey that collaboratives are developing and need support. This could come from NHS England across a range of themes, including testing governance models, managing delegations from ICBs or NHSE, handling risk and creating a collaborative culture across organisations. There is also a call for organisations such as the NHS Confederation and NHS Providers to offer peer learning opportunities, develop case studies and share best practice. Trusts are committed to collaboration and realising the benefits they can bring. The ability to access the right support will help collaboratives realise their potential to make a transformational contribution to care in their systems.

References

- NHS England (2021), Working together at scale: guidance on provider collaboratives. www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/ uploads/2021/06/B0754-working-together-at-scale-guidance-on-provider-collaboratives.pdf

- NHS England, NHS-Led Provider Collaboratives: specialised mental health, learning disability and autism services. www.england.nhs.uk/mental-health/nhs-led-provider-collaboratives

- The Health Foundation (2013), Quality improvement made simple: what everyone should know about health care quality improvement. https://reader.health.org.uk/QualityImprovementMadeSimple

- NHS England (2021), Working together at scale: guidance on provider collaboratives. www.england.nhs.uk/publication/ integrated-care-systems-guidance/#provider-collaboratives

- NHS England, NHS-Led Provider Collaboratives: specialised mental health, learning disability and autism services. www.england.nhs.uk/mental-health/nhs-led-provider-collaboratives

- NHS England (2021), Working together at scale: guidance on provider collaboratives. www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/ uploads/2021/06/B0754-working-together-at-scale-guidance-on-provider-collaboratives.pdf

- NHS England (2021) Working together at scale: guidance on provider collaboratives. www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/ uploads/2021/06/B0754-working-together-at-scale-guidance-on-provider-collaboratives.pdf

About us

NHS Confederation

The NHS Confederation is the membership organisation that brings together, supports and speaks for the whole healthcare system in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. The members we represent employ 1.5 million staff, care for more than 1 million patients a day and control £150 billion of public expenditure. We promote collaboration and partnership working as the key to improving population health, delivering high-quality care and reducing health inequalities. For more information visit www.nhsconfed.org

NHS Providers

NHS Providers is the membership organisation for the NHS hospital, mental health, community and ambulance services that treat patients and service users in the NHS. We help those NHS foundation trusts and trusts to deliver high-quality, patient-focused care by enabling them to learn from each other, acting as their public voice and helping shape the system in which they operate. NHS Providers has all trusts in England in voluntary membership, collectively accounting for £104bn of annual expenditure and employing 1.2 million staff. For more information visit www.nhsproviders.org